The anatomy of family murder - the patterns and warning signs

It’s the most shocking and grisly of crimes: a seemingly everyday person suddenly, savagely, inexplicably, kills themselves and their kin. We find family annihilation too horrific, too cruel to grasp, so explain it away as random acts of lunacy. But Godfrey Holmes says there are patterns and warning signs – and if we learn to look for them, we may begin to stem the bloodshed

Just one week ago, on the evening of Saturday 19 March, a generally quiet north London neighbourhood, Finsbury Park, was rocked by a terrible crime, when two toddlers were found with critical injuries. A man, said to be the birth father, has been arrested and charged with murder and attempted murder. Three of the more restrained headlines in response to these attacks read, depending on which newspaper one read: “Man arrested over murder of one-year-old boy as his twin sister fights for life – after alleged hammer attack” (Daily Mirror); “Man arrested on suspicion of murder after mother heard screaming for help as one-year-old boy is killed and sister is fighting for life”, (The Daily Telegraph); and “Distraught mother ran into street screaming ‘my kids, my kids’ after finding her son beaten to death with a hammer” (MailOnline).

The case has been set for a plea hearing in June, with a provisional trial date in September. The arrested man has yet to enter a plea and we must not second-guess the facts in this tragic case. However, this was the third distressing instance of multiple family victims nationally in just three weeks. And those only the ones known to any audience beyond the local newssheet.

Less than two weeks before the Finsbury Park incident, police in Stowmarket found 65-year old carpenter and decorator Richard Pitkin dead. Also dead in the extended family home that used to boast a tea room was Sarah Pitkin, 58. The Pitkins, by report, were well-liked and respected. Police were “not looking for anyone else in connection with their inquiries”.

Stowmarket is a fairly small Suffolk town. Wolverhampton, by contrast, is a city of 250,000 inhabitants. But, just three days after news of the Stowmarket tragedy, the people of Wolverhampton were nonetheless alarmed to read in their copies of the Birmingham Mail: “Man killed sister and knifed mum before killing himself”. Had citizens and neighbours in that part of the Black Country turned to The Sun, even less would have been left to their imaginations: “Maniac knifeman stabbed his sister to death and injured his mum before turning blade on himself in bloodbath at flat”.

***

So in cases where there is family annihilation, what is it and why and why does it happen?

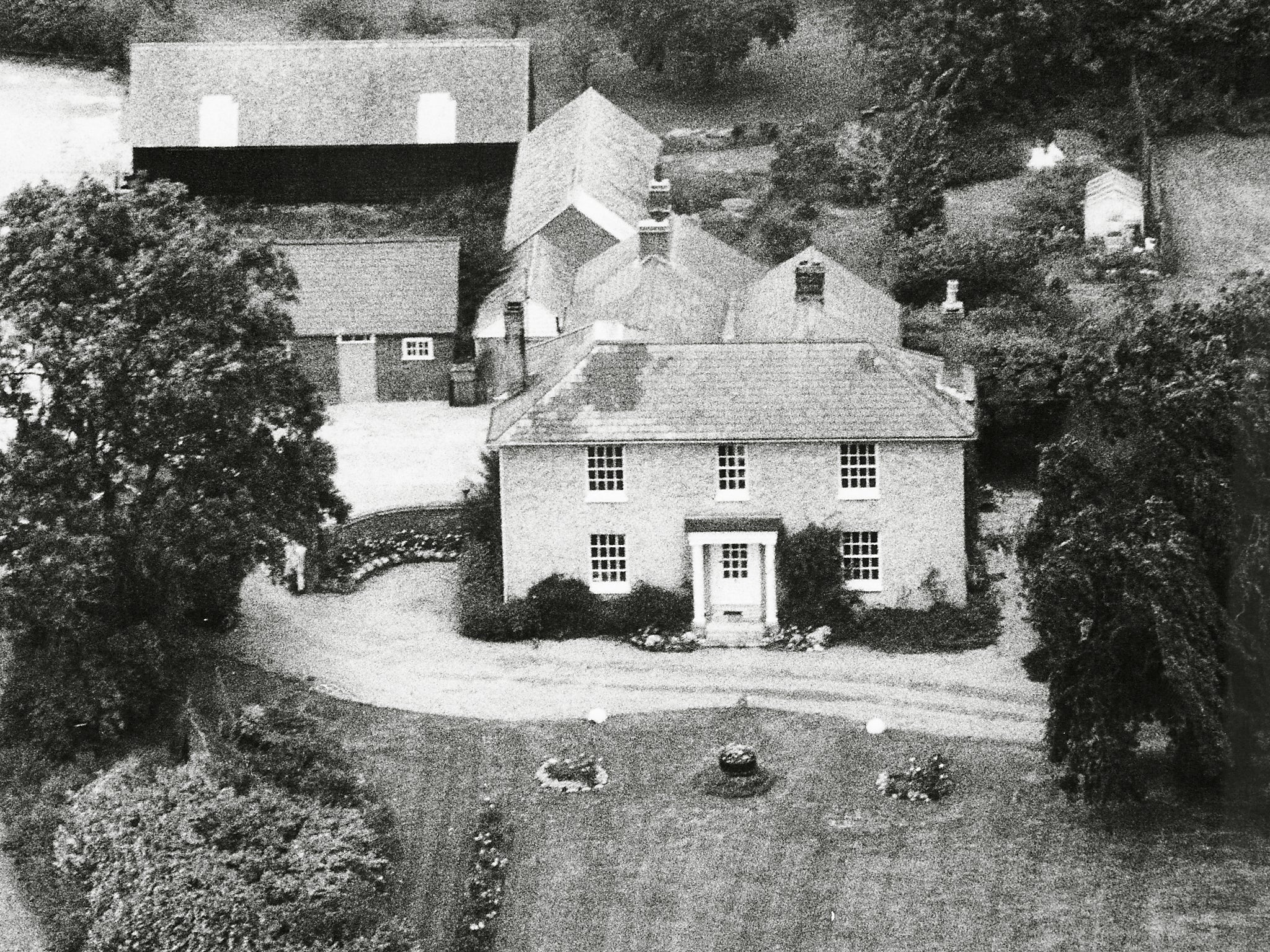

One of the most infamous family annihilations ever took place in sprawling White House Farm, Essex, on 7 August 1985. Sheila Bamber, her parents Neville and June Bamber, and her sons Nicholas and Daniel, were all killed that fateful day. Worse, Sheila’s brother Jeremy Bamber, then aged 24, apparently staged everyone’s murder as if Sheila herself were the culprit. Homicide/suicide, surely? Police who initially attended the scene – ironically in response to a panicked-sounding telephone call from Jeremy – seemed content to accept that interpretation.

For weeks lasting into months, that narrative amazingly stayed unchallenged; and it is fair to say the incarcerated Bamber still maintains his absolute innocence three decades after his belated conviction and life sentencing.

Conventional instances of homicide/suicide where the perpetrator cannot go to jail because he – it is statistically far more likely to be a he – is already dead, either at the scene of horror or perhaps at some secluded beauty spot nearby – tend to have 10 common features.

The historical cases show is that in murder-suicides, first, the killer is, as said, likely to be a man: where familial, a son, brother or father rather than daughter, sister or mother. Second, isolation is frequently a factor, if not the deciding factor: geographical isolation, psychological or psychiatric isolation, perceived isolation within the family – bullying, deprivation, marginalisation, or isolated status, disgrace.

Third, often the perpetrator is consumed with hatred: sometimes hatred is fuelled by resentment. And, fourth, one influence persuading someone to attack his own family so viciously is frequently a grudge: expulsion from the home, threatened separation, refusal of money, not being mentioned in a will, unfair accusations, a partner’s alleged infidelity – or even something as trivial as “you’re forever nagging”.

Fifth, the instrument of death is more often than not extremely violent: gun, sword, knife or hammer are preferred over suffocation or gassing. However, in recent years, fire appears to have been used more, perhaps because perpetrators are more aware of the importance of destroying DNA evidence, and with the terrible “bonus” that it is the fire or the smoke or both doing the killing, not the instigator.

Sixth, typically escape routes are blocked, and a time chosen when the family are near-at-hand, sleeping or watching TV. Keys are hidden. Those who rush upstairs are pursued. And those who rush downstairs are trapped. Elaborate precautions are taken that a getaway car is not to hand – except for the killer’s use. Also, that killer needs to be faster down the street were one of his intended victims to achieve temporary freedom.

Seventh, it is likely that there have been “lesser” preparatory and experimental attacks before the final showdown. For example, survivors of domestic violence typically endure between 20 and 200 assaults before sounding the alarm and calling on neighbours, trusted siblings, or the police. Perhaps the family car is in an inexplicable crash. Or prowlers, maybe suspected of “mere” rogue-trading or peeping Tom-ery, are been seen near the later site of execution.

Eighth, pleas for mercy are routinely and callously ignored. Ninth, the perpetrator usually neither expects nor tolerates retaliation. He likely relies on past romance or deep-seated trust placed in him as “one of us” to deter any last-minute fracas.

Women’s aid, women’s assertiveness, women survivors’, and women’s self-defence groups place emphasis on attempting realistic self-protection. Naturally it is a truism that fighting back is risky, statistically abortive, sometimes provocative prior to an even worse fate, or very occasionally peremptory: a false alarm. Nobody should expect doomed family members always to have a heavy chair or flower-pot to hand – but advice is sensibly given that if you are going to die in any case, you might as well attempt some resistance. And there is rare forensic evidence that the escaping man, whether or not he later self-harms or takes his own life, bears scratches, bruises, cuts or organ-damage that must have been inflicted by one, more, or even all, his targets.

Finally and disturbingly, tenth, if the killer dies during or following his act of family annihilation, could well be set to be pitied rather than blamed: “Poor soul” ; “Must have borne terrible suffering in the Army, at work, as a child...”; “ Moment of madness” ; “Wonderful dad” ; “Not round to put the record straight”, whatever. And this (probably undeserved) taking into account of past misfortune has possibly been orchestrated by the killer long before the act. Maybe letters have been written, certificates displayed, thousands of pounds raised for charity, compensation successfully awarded... anything to perpetuate a story of awful injustice, noble self-abnegation, valid self-sacrifice. Because the killer’s unbelievable – yet curiously tenable – accomplishment is to write the first version of history.

History he has himself fulfilled. History he has himself shaped. Maybe history could supply us with detailed statistics for (a) homicide/suicides; and (b) whole- family killings not attributed to an integral, or past, members of those threatened families? No such fortune. Whereas homicides (murders) appear in one table of figures, Suicides (sometimes attempted suicides) appear in other lists. Even then, statistic-gathering is chaotic, partly due to coroners hesitant to issue suicide verdicts.

Do other countries perhaps keep better records? No. What we do know is that family annihilation is occasionally cultural; also imitative. South Africa is blighted with two kindred phenomena: isolated Boer and/or white men, on the margins, killing their entire families then themselves; alternatively, a son: not impossibly a black or mixed-race son, killing his parents, maybe his siblings as well, with appropriation of assets an attributed motive.

As for the US, comparisons with UK family-killings are ever more fraught with difficulty. Guns and harmful weapons far more available than in Britain, and spree-killings of all types are hard to separate out from targeted killings of a culprit’s relatives, say with one or two bystanders also killed or injured. “Home invasions” in the States are certainly frequent – but as few as 100 people each year die as a direct consequence of burglary or attempted burglary within the broken-into home; compared with at least 18,000 US suicides – labelled suicides – each year.

Is alcohol an important component, giving the instigator more courage? Or are perpetrators drug-dependent? The jury is still out over mitigation. Who knows whether a killer with little or no regard to his own safety, his own discovery, his own lifespan, would have been more restrained with more inhibitions. Harmful substances certainly don’t seem to reduce instances of family annihilation – or their intensity.

***

So where do “my” 10 common factors leading to family annihilation leave we who survive; we the relations and friends who are not subject to our own family’s annihilation or someone else’s; we who read about it from the comfort of our armchairs; we who are safe, secure, cherished and uplifted at home? A difficult quandary. Arguably, more difficult in the aftermath of family annihilation than in the wake of almost any other crime, any other catastrophe, even any other “unforeseeable” disaster.

Nor do the police, the courts, psychiatrists, or social workers – those whose daily employment is to help those in distress, but not this degree of distress – give the rest of an easy lead; give us reasons, perhaps in reply to that familiar plea: give us a clue! Society buries family annihilation (undertakers, literally) because the subject is too painful; it is seemingly too far beyond comprehension. Maybe falsely, family annihilation is considered a flash-in-a-pan; perhaps it is put down far too quickly to the mental illness of which it is “so obviously” a manifestation; and crucially there is rarely a survivor, less so an attendant survivor, to enlighten either the authorities or the public.

Police, press, parliament, the Church, social services, the NHS, everyone most likely to be listened to, can usefully move on to more pressing issues – because there is there is nobody to prosecute, and/or nobody who can be subject of a child protection conference, and/or nobody who can be reassessed as a risk; or else the intentional killer who is an accidental or purposeful survivor makes a full confession. In which case there are only three available “disposals”: long-term imprisonment, enduring committal to hospital, or leeway enough, without intention, for the prisoner to finally take his own life (far more likely, statistically, if he lived through an initial attempt so to do).

Ironically, society’s certainty that “it’s all over and done with” militates against prevention, mitigation, avoidance, of family annihilation in the future. So onlookers and professionals alike are tempted to close the chapter, to let bygones be bygones. Instead, it is beholden on everyone to take account of warning signs: buildups of spite and resentment; previous domestic violence; acrimonious divorce and separation; bankruptcy; custody and access sessions denied or giving rise to concern; threats.

Because threats are not always empty. What everyone takes to be bragging, bad-mouthing, intimidation or hyperbole might actually be a signpost to future family annihilation. So statutory reviews must in future be held before the event, not after.

***

Which brings me to my own commitment to find out more concerning family annihilation. That prompt came from four instances a little too near where I lived for comfort.

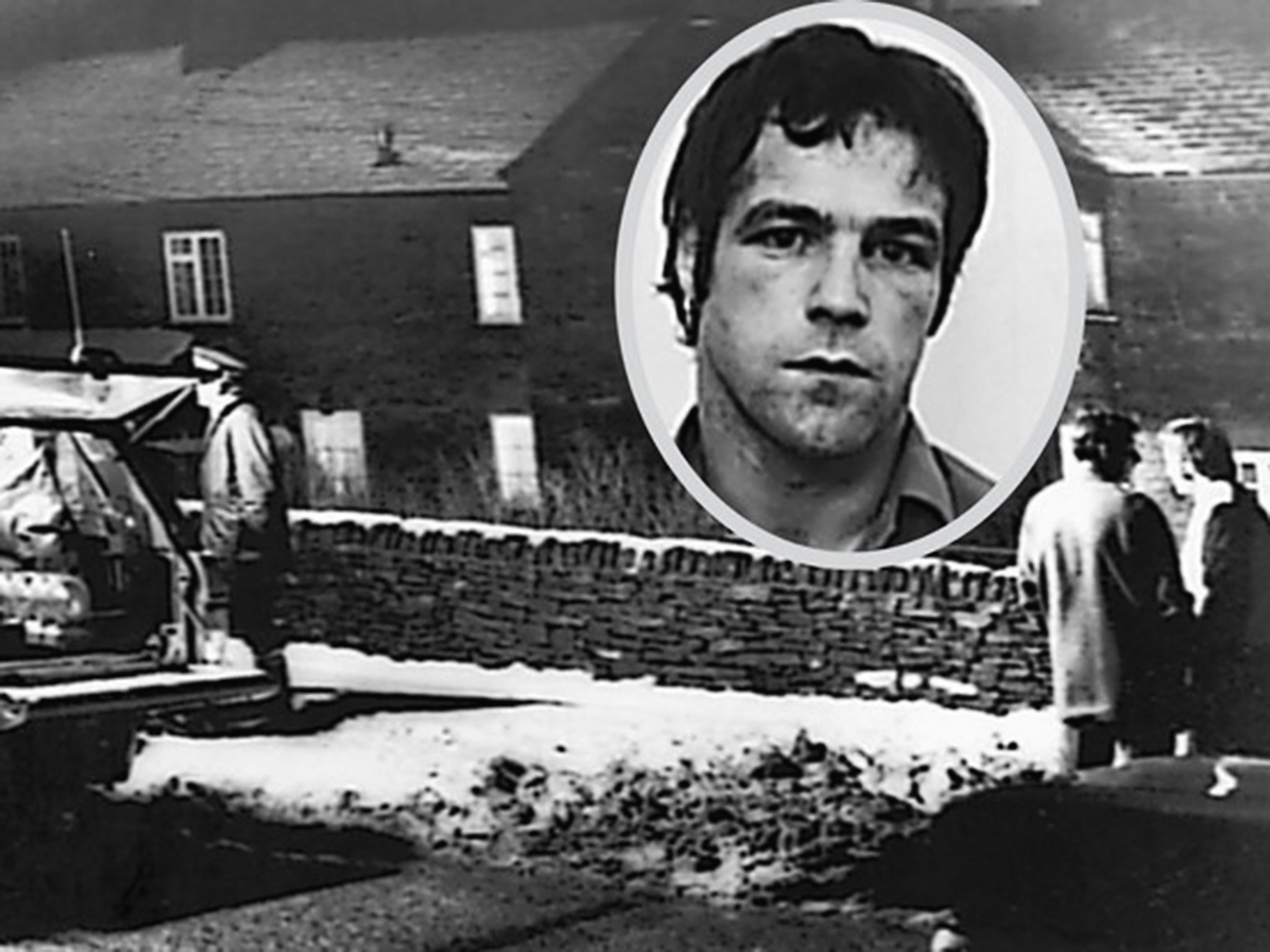

2017 marks 40 years after escaped prisoner Billy Hughes, now deceased, took a family hostage at a cottage in Eastmoor, near Baslow in Derbyshire, butchering Grandma, Grandad, the couple’s son-in-law and their granddaughter. Only Mum survived the Pottery Cottage Murders, even she within seconds of her own shooting or knifing. And Eastmoor is just four miles up the road from where for more than three decades we made our home.

Six years later came the Dore Wedding Day Massacre. A talented pupil, who had been taught by my wife, crouched in her bedroom, in an affluent suburb of Sheffield, towards the end of the family celebrations that crowned her elder sister’s marriage ceremony just hours earlier, and listened, listened, as every single member of her cherished family to hand – solicitor father, doctor mother, older brother – faced arbitrary execution at the other side of her hasty barricade. Grim. With worse for this young woman still to come. And all at the hands of a robber – not a relative.

Came the day 10 years after that: at the time a I was a local government officer charged with supervising three children’s access to their mother at a voluntary-funded contact centre. I was returning from the centre when I heard that, in a lay-by just a few miles down the same road I was driving along, a jealous father, also a centre user, had had set light to himself and his two sons – by a woman he had acrimoniously split from – within the exactly parked car he had used for access to the children. Three bodies discovered within. No lads able to survive their ordeal, survive their access, and see their mother again; nor chance that mother should encounter, look after, love, her boys again. Total immolation. Total elimination.

One “final” coincidence: from 2011 to 2014, when I needed my car in the evening, I chose to park it at the other end of the alley opposite where I’d moved to. And one enchanting summer afternoon, the cul-de-sac was full of police cars, sentries, men in white suits. I had not consciously registered the house before. It was semi-detached, privately owned, on the outer edge of a large post-war municipal estate. In succeeding days, I soon learnt a Stepdad had murdered the widowed shopkeeper he had recently married, then laid on the same bed and stabbed himself to death. All because she had told him she had had enough.

In the face of such terrible calumny, in the light of such unimaginable discoveries, most observers, most survivors, most people holding Twitter or Facebook accounts, most readers of newspapers, will remain baffled as to why anyone, anywhere, would want “to take them (those the murderer has known or loved) all with me” – thus – “releasing them from agony”. Is this really the freedom from oppression a “crazed” killer yearns for? Or is this too speedy an escape from life’s trials and tribulations; too convincing a hope of a Better World than that into which we were all born?

Purportedly, family annihilation, family extinction, is absolute love – absolute hatred? – expressed absolutely. And whatever the reasoning behind it, this is an act committed so suddenly, so ruthlessly, so willfully, it permits no second thoughts. No opportunity for reverse. No retrieval.

Three cases of family annihilation across the UK

1) Christopher, aged 50, shot dead his wife, 49, and daughter, 15, before gunning down their horses and dogs and then setting alight his £1.2m Shropshire home in 2008. The former mattress and pizza-box salesman had made himself into a millionaire, but his business interests collapsed, leaving him in £4m of debt. Some say he killed his family in a crazed attempt to “protect” them from poverty they were about to face. The killer was caught on CCTV on the night of the blaze walking his mansion's grounds carrying a bucket, a rifle and lighter fluid for setting the fire.

2) The bodies of a mother, 44, her son, 13, and daughter, nine, were found in February 2011. The mother’s husband was working abroad. Police broke into the family’s detached house, in the Midlands, after they were contacted by a concerned relation. The children were found in their bedrooms with stab wounds to their neck and chest. Their mother, a devout Roman Catholic, was in the bathroom with multiple knife wounds to her arms. An inquest heard that the woman’s mother called police after she was unable to contact her daughter. Police investigated the tragedy as a suspected double homicide-suicide.

3) A report into the care of a North-east of England ex-soldier, who shot dead four members of his family in 2006, found failings in the mental health care he received. David, 41, killed his aunt and uncle, both 70, and their sons – David’s cousins – aged 41 and 44. He was sentenced to a minimum term of 15 years after admitting manslaughter. There was reportedly a lack of communication between agencies.