Adolf Hitler's Nazi deputy Rudolf Hess ‘murdered by British agents’ to stop him spilling wartime secrets

Surgeon claims Hess was killed on British orders to preserve wartime secrets

Scotland Yard was given the names of British agents who allegedly murdered the Nazi Rudolf Hess in the infamous Spandau Prison but was advised by prosecutors not to pursue its investigations, according to a newly-released police report.

Written two years after Hess’s death in 1987, the classified document outlines a highly-sensitive inquiry into the claims of a British surgeon who had once treated Adolf Hitler’s deputy that, rather than taking his own life, the elderly Nazi was killed on British orders to preserve wartime secrets.

Released under the Freedom of Information Act, the partially-redacted report by Detective Chief Superintendent Howard Jones revealed that the surgeon - Hugh Thomas - had supplied him with the names of two suspects provided by a “government employee” responsible for training secret agents.

Withheld for nearly 25 years, the report has been released by the Yard’s counter-terrorism command following consultation with “other Government and foreign government departments”.

The death of Hess in Berlin at the age of 93 after he apparently hung himself with a wire flex in a summer house in the grounds of Spandau has long been controversial with claims that he was too infirm to commit suicide and a farewell note to his family had in fact been written 20 years earlier.

The Yard was called in in 1989 after Mr Thomas, an eminent former military surgeon previously based in Spandau, claimed in a book that “Hess” was in fact an impostor sent by the Nazis to Britain in 1941 and his murder was carried out by two British assassins disguised as American serviceman.

In his subsequent 11-page report, Mr Jones said the surgeon had “confidentially imparted” the names of two alleged suspects passed to him by an informant who was a former member of the SAS and had since taken on a role “training people for undercover or spying operations”.

Prior to his death, speculation had been growing that Hess might be released because a long-standing veto by the Soviet Union, which for decades had insisted on a severe regime for Hess, including forcing him to wash his hands in toilet bowl, might be reversed by Mikhail Gorbachev.

Mr Jones wrote: “[Mr Thomas] had received information that two assassins had been ordered on behalf of the British Government to kill Hess in order that he should not be released and free to expose secrets concerning the plot to overthrow the Churchill government.”

The officer found there was not “much substance” to Mr Thomas’s claims of murder but suggested that efforts should be made to trace and interview the alleged killers along with other witnesses to ensure the matter could be “comprehensively adjudged” to have been fully investigated.

It is not known if the two suspects were tracked down after the report was submitted to the Crown Prosecution Service in May 1989.

But within six months the investigation was declared closed after the then Director of Public of Prosecutions, Sir Allan Green QC, advised that further inquiries were not necessary.

In November 1989, Sir Nicholas Lyell, the solicitor general, told Parliament: “The inquiries carried out by Detective Chief Superintendent Jones have produced no cogent evidence to suggest that Rudolf Hess was murdered; nor, on the view of the Director of Public Prosecutions, is there any basis for further investigation.”

The unannounced arrival of Hess in Britain was one of the strangest incidents of the Second World War and remains the subject of extensive debate about its motivation, including whether it was an ill-judged attempt to unseat Winston Churchill by enlisting aristocrats with Nazi sympathies.

After flying solo to Scotland in 1941, Hitler’s deputy fuhrer parachuted to the ground and, after being taken into custody at pitchfork-point by an astonished ploughman, declared his intention to negotiate a peace with Britain to form an alliance against Stalin’s Soviet Union.

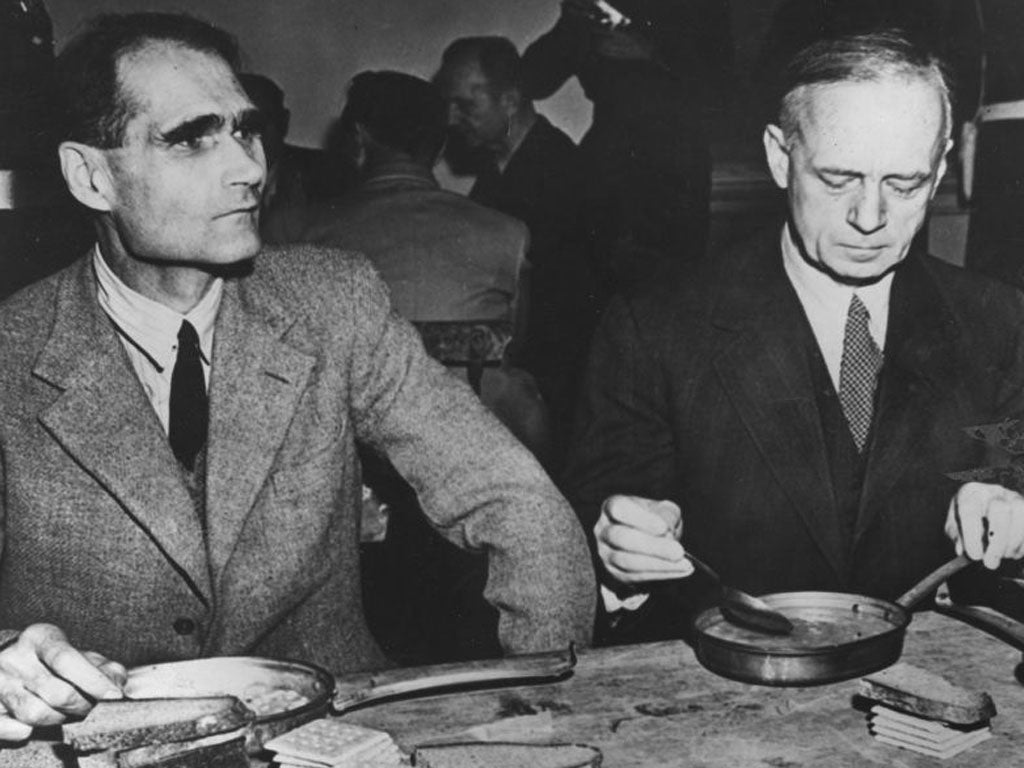

Hess was sentenced to life imprisonment as a war criminal at the Nuremberg Trials and incarcerated in Spandau along with other prominent Nazis including Albert Speer. From 1966 onwards, Hitler’s deputy - whose Allied guards were required to only address him as Prisoner Seven - was the sole inmate in the 600-cell prison.

Further doubt was claimed to have been cast last year on the circumstances of Hess’s suicide when photographs emerged of the summer house where he died, showing the short distance - some 5ft - between the cord from which he was found hanging and the floor.

His son, Wolf, had previously insisted that the height was insufficient for his father, crippled by arthritis, to hang himself and added to post mortem examination evidence suggesting a full noose had been placed around his neck.

In his report, Mr Jones dismissed such concerns, saying expert advice showed Hess’s injuries were consistent with an “unusual hanging situation”.