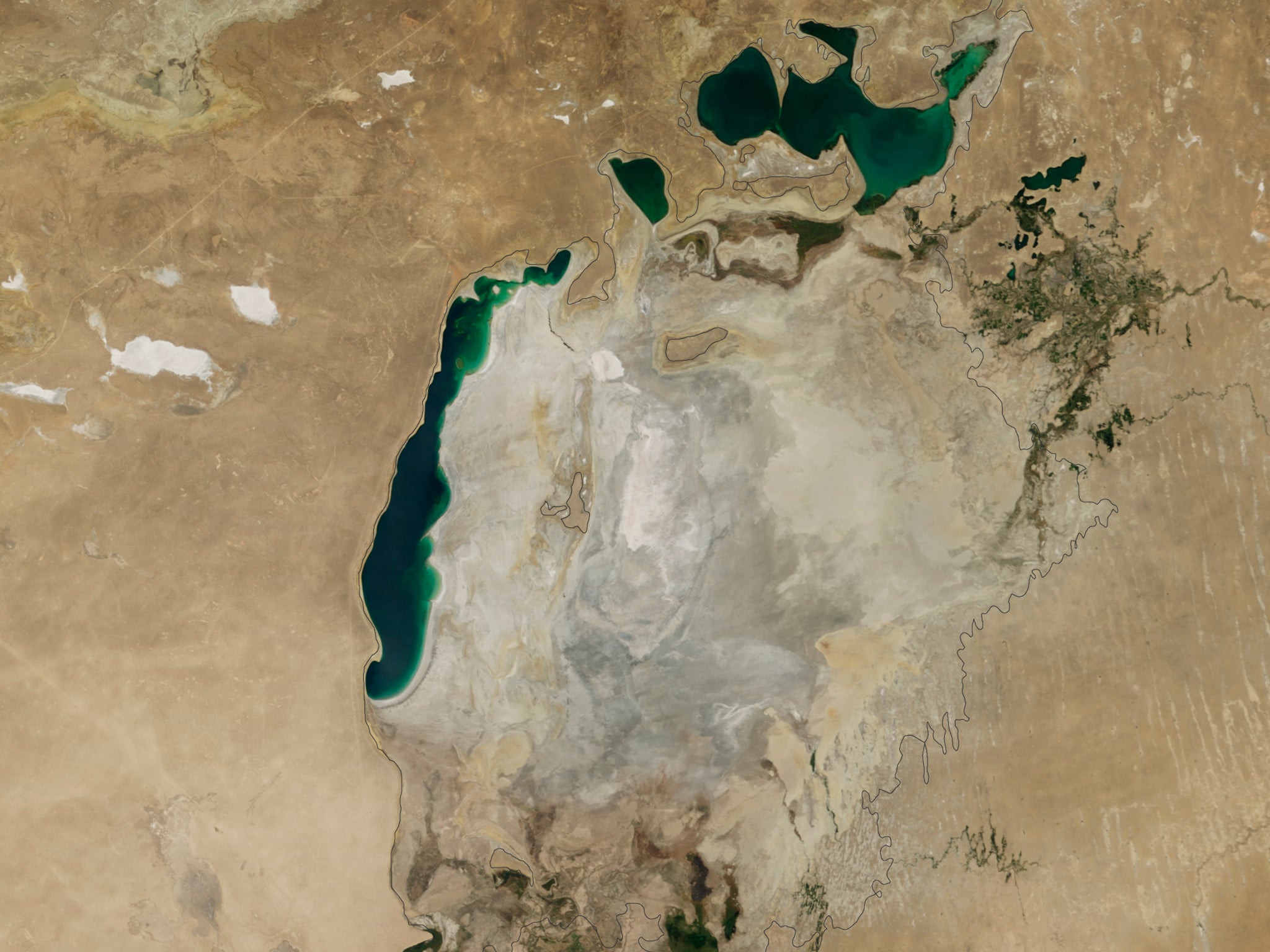

The Aral Sea: Nasa pictures show how what was once the fourth largest lake in the world has become almost completely dry

A massive Soviet irrigation project in the 1960s has seen the Aral Sea retreat by an alarming extent over the last half-century

It was once the fourth largest lake in the world, but what used to be an expanse of water in the basin of the Kyzylkum Desert now lies almost completely dry.

The Aral Sea has been retreating over the last half-century since a massive Soviet irrigation project diverted water from the rivers that fed it into farmland.

Images taken from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer on Nasa's Terra satellite have now depicted how since the turn of the century the lake has increasingly shrunk until this year saw its eastern lobe dry up completely.

The lake was at one time fed by the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers which flow down from the mountains before making their way through the Kyzylkum Desert where they pooled together at the lowest part of the basin.

An irrigation project by the Soviet Union in the 1960s however took water from the rivers to transform the desert into cotton farms.

While the massive diversion of water allowed the desert to thrive, it had a devastating effect on the Aral Sea.

This series of images starts in the year 2000, by which time the lake was already a fraction of what it was before the irrigation project started in the 1960s.

The images, taken each year in the month of August, show how the smaller Northern Aral Sea had separated from the Southern Aral Sea, which itself had broken up into an eastern and a western lobe, the two sides still barely connected at both ends.

The following year however this connection had been broken and the eastern part, although larger in surface area, rapidly disappeared in the subsequent years.

While there appears to have been some fluctuation between 2009 and 2014, as a result of alternately dry and wet years, the overall pattern sees the eastern lobe consistently shrink until dry conditions this year caused it to completely disappear.

In 2005, Kazakhstan built a dam between the Northern Aral Sea and the Southern Aral Sea in a bid to save part of the lake, according to the Nasa Earth Observatory.

The changes have also brought dire consequences to the people surrounding the lake, with the communities that depended on them collapsing as the water dried up.

Meanwhile, the water left in the lake became polluted with fertilizer and pesticides, which has caused a public health hazard now contaminated dust is blown up from the exposed lakebed, the Nasa Earth Observatory reports.

To compound matters, more water has been taken from the rivers to flush out the cropland affected by the blowing contaminated dust.

The loss of the water has also made the winters colder while the summers have become hotter and drier.

In 2010, a documentary depicted the dramatic desiccation of the Aral Sea, which has now become a byword for ecological calamity.

At that time the lake still covered half of its original area of 25,500 square miles, while the volume of water had been reduced to a quarter, according to the We Are Water Foundation.

Spanish director Isabel Coixet made the film for the foundation, which seeks "to enable the equitable development and sustainable management of the world's water resources."

At the time the foundation said: "The region has the highest infant mortality rate in all of the former USSR" and "chronic bronchitis has increased by 3,000 per cent and arthritis 6,000 per cent, and in part of Uzbekistan" liver cancer has increased 200 per cent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments