Working on the 'God particle' saved my life, says Peter Higgs

The Nobel prize-winning physicist Peter Higgs has described the fame he has endured since the discovery of his “God particle” as “a bit of a nuisance” – but admitted that it his was his work that “kept him alive” during the breakdown of his marriage.

The scientist, whose theory on the Higgs boson named after him is widely regarded the most significant development in particle physics for generations, was speaking about how the stress of his research led to the breakdown of his marriage to Jody, an American linguist, in 1972.

“When my wife and I got married, she thought of me being an easygoing person and I warned her I wasn’t,” said the 84-year-old.

“I was easygoing in terms of being adaptable in my social life. But maybe I suffered a personality change in the mid-Sixties and became more dedicated to things involving work because it had become successful in some way.”

Professor Higgs has never been comfortable with the fame his theory brought him but fame would have seemed a far-off prospect in 1964 when he first proposed the theory of an invisible field strewn across space that gave mass to every object in the universe.

The idea was initially met with suspicion and even ridicule in certain circles. His first paper was rejected by a journal, and some peers accused him and some colleagues of failing to grasp the basic principles of physics.

“Nobody else took what I was doing seriously, so nobody would want to work with me,” he told BBC Radio Four. “I was thought to be a bit eccentric and maybe cranky.”

The son of a BBC sound engineer from Newcastle, Higgs graduated with a first-class honours degree in physics from King’s College London in 1950. He was denied a lectureship at the university, however, so became a researcher at Edinburgh University.

Upon publication of his work on the particle in 1964, he and his colleagues were widely dismissed as young pretenders, with some even suggesting they should abandon their research or risk “ professional suicide”.

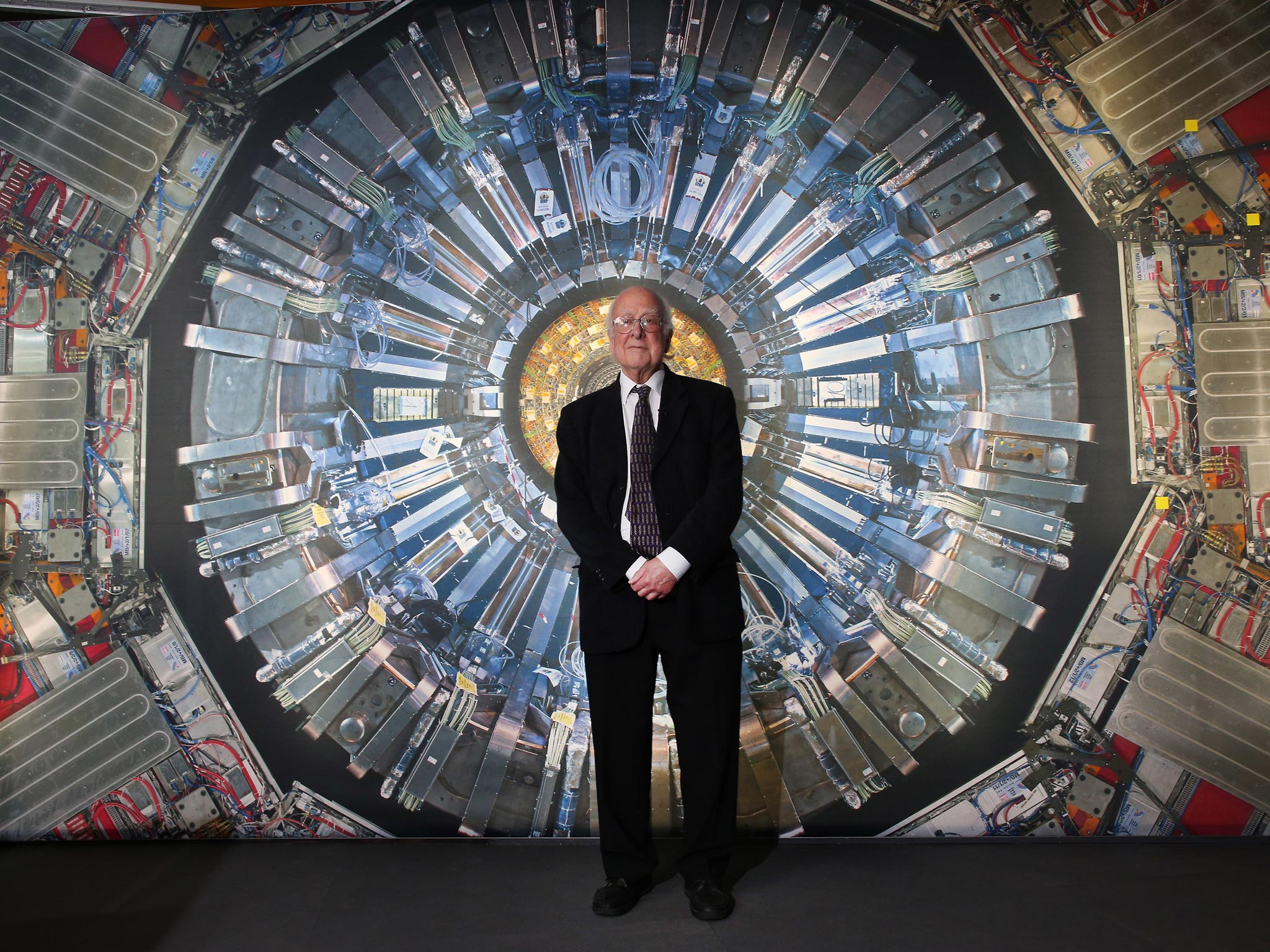

It was 48 years later that his radical concept was finally proved correct by a team of physicists using the Large Hadron Collider at the Cern laboratory in Geneva.

After the discovery of the particle Higgs shared the Nobel prize with Belgian François Englert. But Higgs described the experience of suddenly becoming one of the best-known scientists in the world as “a bit of a nuisance”.

The notoriously shy professor retired in 1996 and became emeritus professor of physics at Edinburgh University. But old age has done nothing to avert the interest in his work from young people.

“If I go to something where there are lots of students, they all want use their mobile phones to take pictures of me,” he said.

“The discovery [of the Higgs boson] has led to a disturbance of my lifestyle,” he added in comments to be broadcast on Tuesday on The Life Scientific. “But it’s time to move on in particle physics now.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks