UK becomes first country in world to approve IVF using genes of three parents

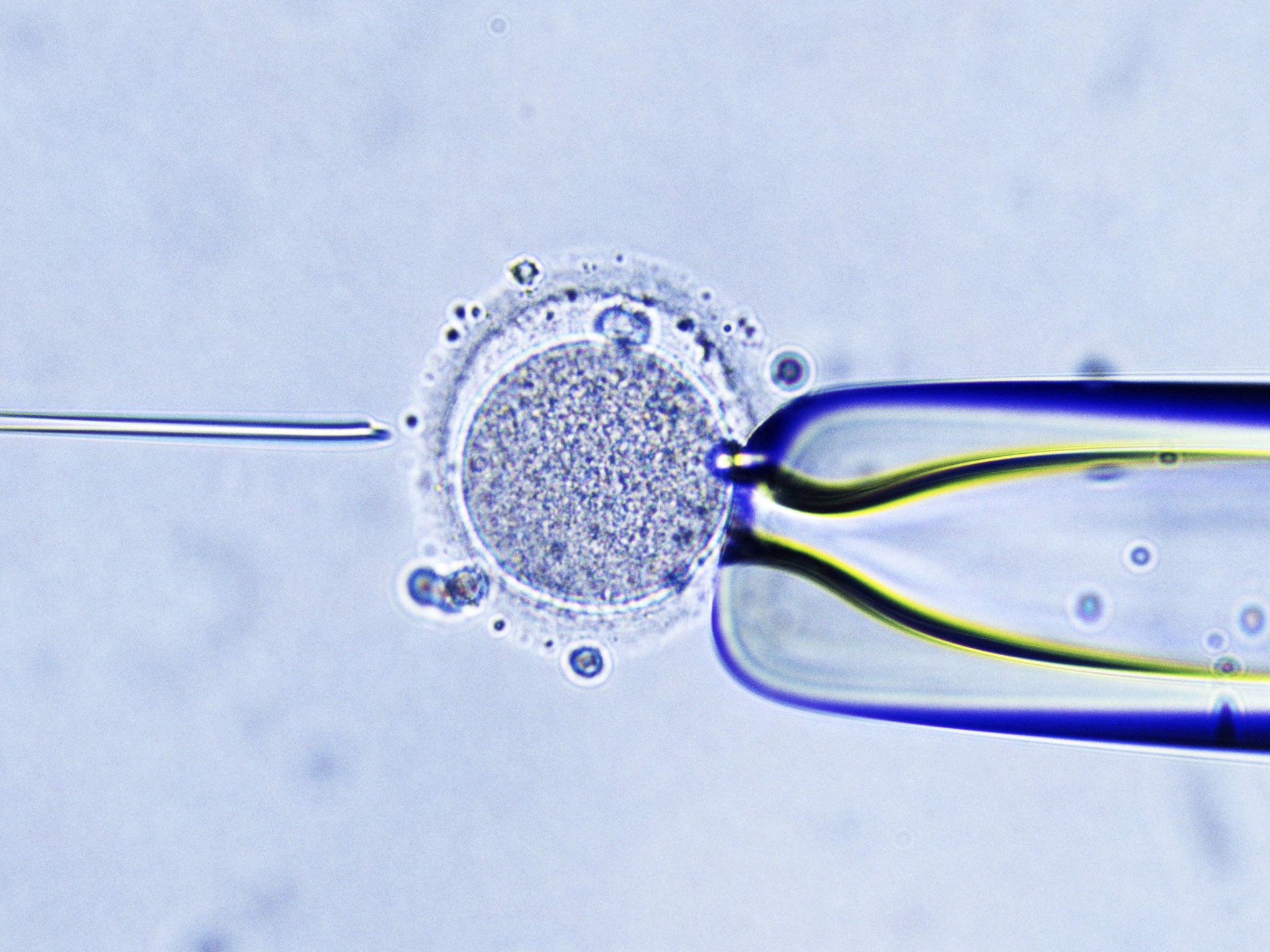

The technique transfers nuclear material from the mother’s egg cell into a donor’s egg

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Britain is set to become the first country in the world to allow a controversial IVF technique that produces embryos with DNA from three people in an attempt to rid some affected families of serious genetic disorders. If Parliament gives the go-ahead, it would mean that Britain would also be the first nation to allow a form of “germ-line gene therapy”, where the DNA of all subsequent generations within a family is changed in order to eradicate inherited diseases.

The Government’s Chief Medical Officer, Dame Sally Davies, said that legislation to allow the use of mitochondrial replacement could be passed by Parliament at the end of next year with the first IVF babies resulting from the technique being born within two years.

“What we are starting to do now is to develop the regulations, consult on these regulations and then to take them into Parliament… I hope then to go forward and we’ll be the first country if we do,” Dame Sally said yesterday.

Inherited defects within the mitochondria – the tiny “power packs” of the cells – affect about one in 6,500 people. Most have mild forms but between five and 10 babies a year are born with a severe form of the disease and it is these children whose lives could be transformed by the technique, Dame Sally said.

“Mitochondrial disease, including heart disease, liver disease, loss of muscle co-ordination and other serious conditions like muscular dystrophy, can have a devastating impact on the people who inherit it,” she said.

“People who have it live with debilitating illness, and women who are affected face passing it on to their children. Scientists have developed ground-breaking new procedures which could stop these diseases being passed on,” she added.

The technique involves transferring the nuclear material of an affected mother’s egg cell into the donor egg of an unaffected woman, whose healthy mitochondria will then be passed on to the IVF baby.

This means that the baby will inherit DNA from three biological “parents” – the mother, the father and the donor woman – but scientists emphasised that less than 0.1 per cent of the baby’s genes will come from the donor in the form of mitochondrial DNA.

Children born from the technique will not be given the right to know the identity of the woman who donated the egg as she will not be officially recognised as a parent, Dame Sally said.

The technique will also mean that all subsequent generations of children born to girls resulting from the procedure would also carry the mitochondrial changes. In Britain, such germ-line gene therapy has been banned and Dame Sally emphasised that there are no plans to lift this ban in the case of nuclear DNA.

“It is the germ-line of your mitochondria that goes down [the generations] but that is quite separate from the DNA of the nucleus which is what makes us what we are… There is no intention of doing anything with the nuclear DNA,” Dame Sally said.

“I am comfortable with this. I think we will save some five to 10 babies born with ghastly diseases and [to an] early death without changing how they look or behave, and it will allow mothers to have their own babies, which at the moment they cannot.”

She added that all children born from the technique will be closely monitored by doctors during their lives for signs of any ill-effects resulting from the IVF procedure, although she emphasised that there is no evidence from animal studies that it can cause medical problems.

“I have to rely on the advice of scientists and what I hear from scientists whom I can trust is that this looks pretty safe. We have no evidence that it is unsafe,” she said.

“There are clearly some sensitive issues here and I’m not trying to avoid them, but since researchers first approached the Health Department in 2010 we’ve been taking views in different ways and it is clear there is general support for these techniques to be used, subject to strict safeguards.”

An extensive public consultation on the procedure by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority found widespread support for the technique but some critics suggested that it will increase the risk of unforeseen health problems as well as raising the prospect of “designer babies”. “These techniques go far beyond anything existing in both invasiveness to the embryo and complexity, so it’s not surprising that they pose serious health risks to the child,” said David King, director of the pressure group Human Genetics Alert.

However, Alison Murdoch, professor of reproductive medicine at Newcastle University, which is pioneering mitochondrial replacement in IVF procedures, welcomed the decision to introduce legislation to allow it.

“This is great news for UK science and gives hope to women who just want a healthy baby. The UK government has made a moral decision,” Professor Murdoch said.

“Our research is leading to a pioneering IVF technology to reduce that risk for mothers who have abnormal mitochondria. There is still more research to do, but this decision means that we could eventually be allowed to offer it as a treatment.”

Mitochondrial replacement has resulted from a revolution in IVF technology and the manipulation of eggs and embryos.

It involves two techniques. One, called maternal spindle transfer, involves switching the nucleus from the mother’s egg cell before fertilisation while the other, called pro-nuclear transfer, involves switching after fertilisation, which results in the destruction of the donor’s embryo.

Gene genius: What the experts say

Sir John Tooke, president of the Academy of Medical Sciences: “Introducing regulations now will ensure there is no avoidable delay in these treatments reaching affected families.”

Dr Catherine Elliott, director, Medical Research Council: “UK scientists are now at the exciting point of being able to turn these techniques into a means of preventing these appalling diseases.”

Professor Doug Turnbull, director, Wellcome Trust Centre for Mitochondrial Research, Newcastle University: “This will give women ... the opportunity to have children free of mitochondrial disease.”

Professor Robin Lovell-Badge, head of genetics, MRC National Institute for Medical Research: “There’s nothing in the science conducted to date to suggest new techniques are unsafe.”

Robert Meadowcroft, chief executive, Muscular Dystrophy Campaign: “We now urge the Government to move with haste, and to draft regulations to share with the public.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments