Triclosan: Soap ingredient can trigger liver cancer in mice, warn scientists

Despite other scientists calling for caution over findings, researchers say chemical may cause similar changes in people

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A chemical ingredient of cosmetics, soaps, detergents, shampoos and toothpaste has been found to trigger liver cancer in laboratory mice, raising concerns about how safe it is for humans, scientists said.

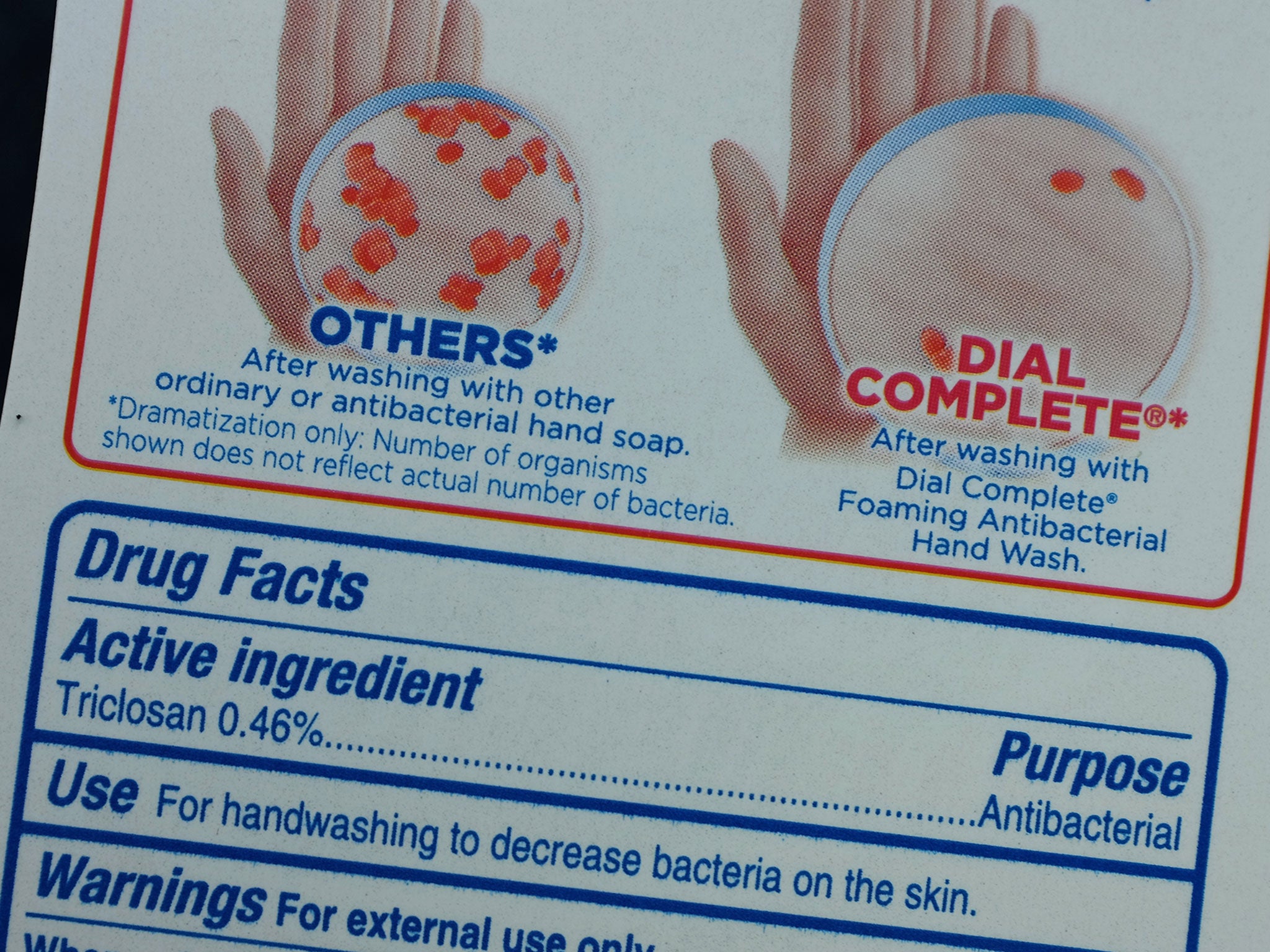

Triclosan, a commonly used anti-bacterial agent added to bathroom and kitchen products, promotes the growth of liver tumours in mice fed relatively large quantities of the substance, a study has found.

The research is the latest to link triclosan with cancer and liver disease, but other scientists have urged caution over the findings suggesting that they do not prove a direct causal link between the chemical and the ill health of people exposed to it.

The study found that mice fed 3 grams of food containing 0.08 per cent triclosan daily for six months suffered liver damage and were more susceptible to liver tumours induced by other carcinogenic chemicals.

By comparison, one gram of toothpaste contains about 0.03 per cent triclosan, and six months in mice is equivalent to about 18 years in humans, the researchers pointed out.

However, the scientists who carried out the latest study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, said that the link between triclosan and liver cancer in laboratory mice is relevant to human health because the chemical may cause similar changes in people.

“Triclosan’s increasing detection in environmental samples and its increasingly broad use in consumer products may overcome its moderate benefit and present a very real risk of liver toxicity for people, particularly when combined with other compounds with similar action,” said Professor Robert Tukey of the University of California, San Diego.

The study suggested that triclosan is damaging to the liver by interfering with a protein called constitutive androstane receptor, which helps to detoxify the blood. To compensate for this interference, the liver overproduces cells, causing fibrosis and cancer, the scientists said.

Traces of triclosan, a synthetic compound not found in nature, have been found in the breast milk of up to 97 per cent of lactating women and the urine of three quarters of people tested, the researchers said.

Concerns about its possible health effects of triclosan have resulted in an investigation by the US Food and Drug Administration, which regulates its use in America. The FDA said that it does not have enough safety evidence to recommend any change to its use in consumer products.

However, Professor Bruce Hammock of the University of California, Davis and a co-author of the study, suggested that the latest findings could lead to changes in the advice to consumers.

“We could reduce most human and environmental exposures by eliminating uses of triclosan that are high volume, but of low benefit, such as inclusion in liquid hand soaps,” Professor Hammock said.

“Yet we could also for now retain uses shown to have health value – as in toothpaste, where the amount used is small,” he said. Triclosan has been shown for instance to help the treatment of gum disease.

However, other scientists were not convinced of the risk to human health.

“Firstly, the mice used in the study were primed with a tumour-promoting chemical before being exposed to triclosan, which humans would not be. And the concentrations of triclosan used were much higher than those found in the environment,” said Oliver Jones of the University of Melbourne in Australia.

Professor Alan Boobis, a pharmacologist at Imperial College, London, said: “Studies in primates showed no hepatic [liver] damage at doses greater than those used in the present study, when administered for 12 months. Whilst it is possible that the carcinogenic effect in mice is relevant to humans, it should be noted that mouse liver tumours are induced by many chemicals, and often they are not relevant to humans.”

Triclosan is a widely-found pollutant

Triclosan was first developed in the early 1970s for use in surgical hospital scrubs and since then it has become the most ubiquitous anti-bacterial component of a wide range of consumer products ranging from shower gel to floor wax.

Its use has increased significantly in recent years with the result that it is a widely-found pollutant. About 1,500 tons of triclosan are produced worldwide each year and much of it ends up in rivers and streams – it is among the seven most commonly-detected compounds in waterways in the United States.

Concerns about its possible health effects led to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ordering an inquiry. So far, however, the evidence does not warrant a change in advice to consumers, it said.

Some studies have linked it with cancer, others with hormone regulation – triclosan may mimic female hormones and so act as a “gender bender” chemical. Other research involving bacteria has even suggested that it could play a role in promoting resistance to antibiotics.

However, other studies have shown that triclosan is beneficial to human health. A 1997 study by the FDA of evidence presented by Colgate showed that triclosan is effective in preventing gingivitis – bacterial gum disease.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments