Three-parent babies explained in six questions: How does it work and who objects?

MPs will vote today on whether Britain should become the fist country in the world to permit the creation of IVF babies with DNA from three different people. The controversial technique could save the lives of around 150 babies a year in Britain - but it has also drawn criticism. Here is The Independent's breakdown of what you need to know

Why are MPs voting today on legalising the “three-parent” baby technique of mitochondrial donation?

Mitochondrial donation is a process whereby the genetic material of three people are merged into a single IVF embryo at the earliest stages of development. This is a form of “germline” modification that will affect the genetic inheritance of future generations within treated families, which is banned under the 2008 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act. The vote today in the House of Commons is about amending that Act by Statutory Instrument in order to exempt mitochondrial donation and to allow women at risk of passing on mitochondrial diseases to have IVF embryos implanted into their womb after undergoing mitochondrial donation.

What does mitochondrial donation involve?

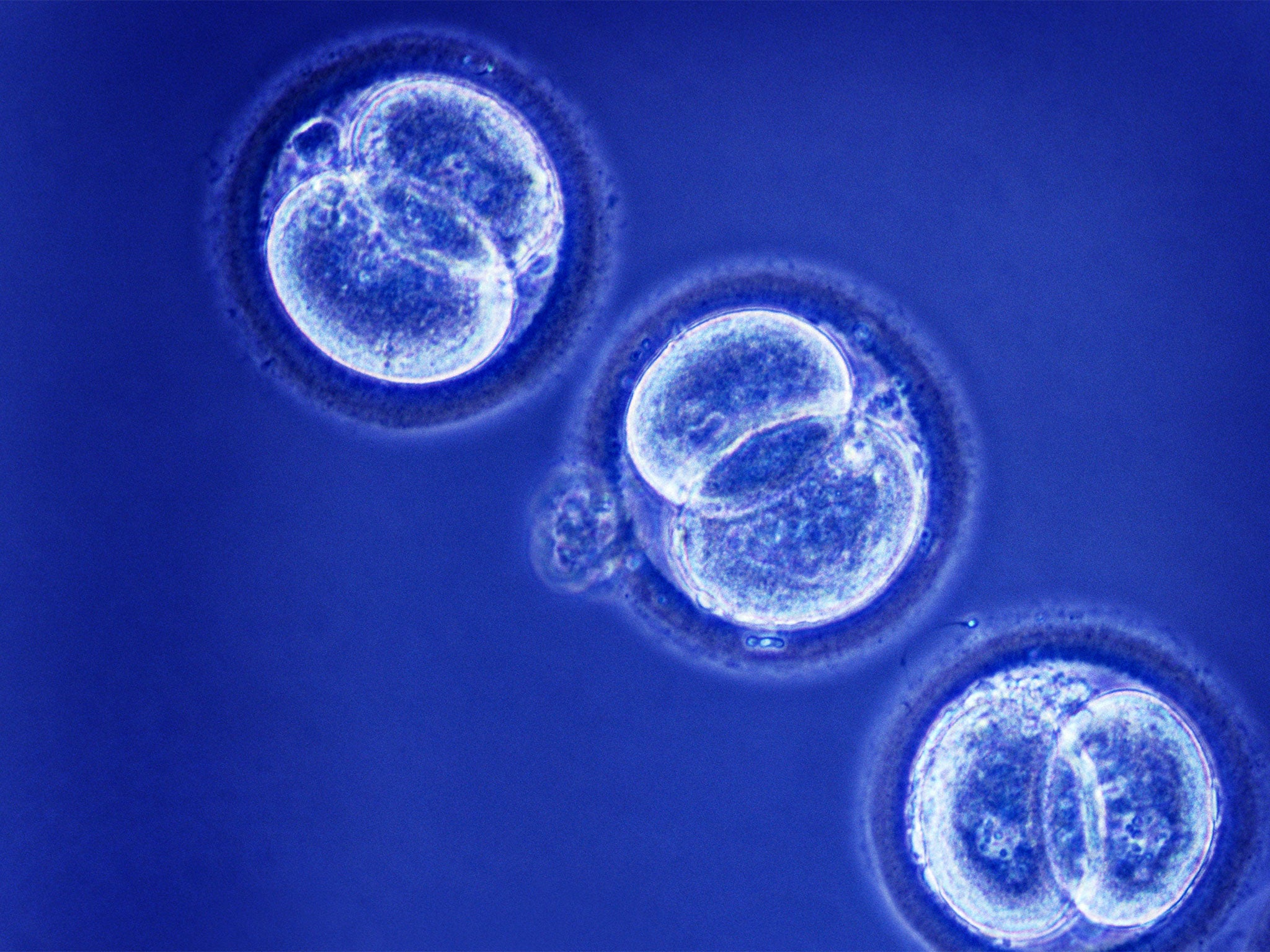

There are three techniques but only one, called pro-nuclear transfer (PNT), is being considered seriously in Britain. This involves transferring the genetic material of the chromosomes within the nucleus of the fertilised egg of an IVF couple into the fertilised egg of a donor which has already had its own nuclear DNA removed. The resulting fertilised egg has the nuclear chromosomes of the mother and father (containing 99.9 per cent of the DNA) and the healthy mitochondrial DNA of the donor woman (containing the remaining 0.01 per cent). Once the resulting embryo reaches a certain stage of development (known as the blastocyst) it is transplanted into the womb of the IVF patient.

Why do doctors want to do this?

There are no treatments for mitochondrial diseases, which affect about 1 in 6,500 babies in the more serious forms. Women at risk of passing them on have few options available to them if they want to give birth to healthy children. They could opt for using donor eggs or, in some cases, a form of pre-natal genetic diagnosis before one of their own IVF embryos is placed back into their womb. Creating IVF embryos using mitochondrial donation offers an opportunity of having their own, genetically related children who are free of mitochondrial defects. Furthermore, the process could mean that mitochondrial diseases are eliminated completely from future generations of that family.

What are the objections?

Some people are opposed on religious or ethical grounds, particularly with pro-nuclear transfer technique which involves creating and then destroying a fertilised egg in order to treat another embryo.

The scientific objections come down to safety, which is why germline modification was made illegal in the first place. Some fear that we do not know enough about “epigenetic” interactions between the mitochondrial genes and the nuclear genes. Others believe that there will be inevitable “carry over” of defective mitochondria from the affected mother’s fertilised egg to the donor egg. These mutant mitochondria could multiply during embryonic development to cause disease, perhaps in way we do not yet understand. This is why, they say, we need to do more research before allowing it to be used on people.

Who are the big players in this debate?

The Anglican church and the Roman Catholic Church are publicly opposed, as are pro-life groups. However, there are several senior scientists who have questioned the safety of the technique as it stands. Most would be happy to see it legalised in Britain but still want a lot more research, particularly on primates, before it is introduced as a clinical procedure. The scientific establishment is robustly supporting today’s amendment with Jeremy Farrar, the head of the multi-billion-pound Wellcome Trust, which is funding research into mitochondrial donation, leading the charge.

If the law is changed what happens next?

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, the regulator of IVF clinics, will be legally allowed to set out the terms of a licence. A team from Newcastle University, funded by the Wellcome Trust, is likely to be the first to apply for such a licence, which is expects to do after October, when the new regulations some into effect. The first “three-parent” IVF embryo could therefore be created later this year, with the first birth in 2016. Britain will become the first country in the world where such a process is allowed in law.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks