The natural historian faces extinction: Overspecialism and funding cuts could end a vital scientific tradition, claim experts

The Government does recognise that there is a problem, although no major steps have yet been taken to address it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

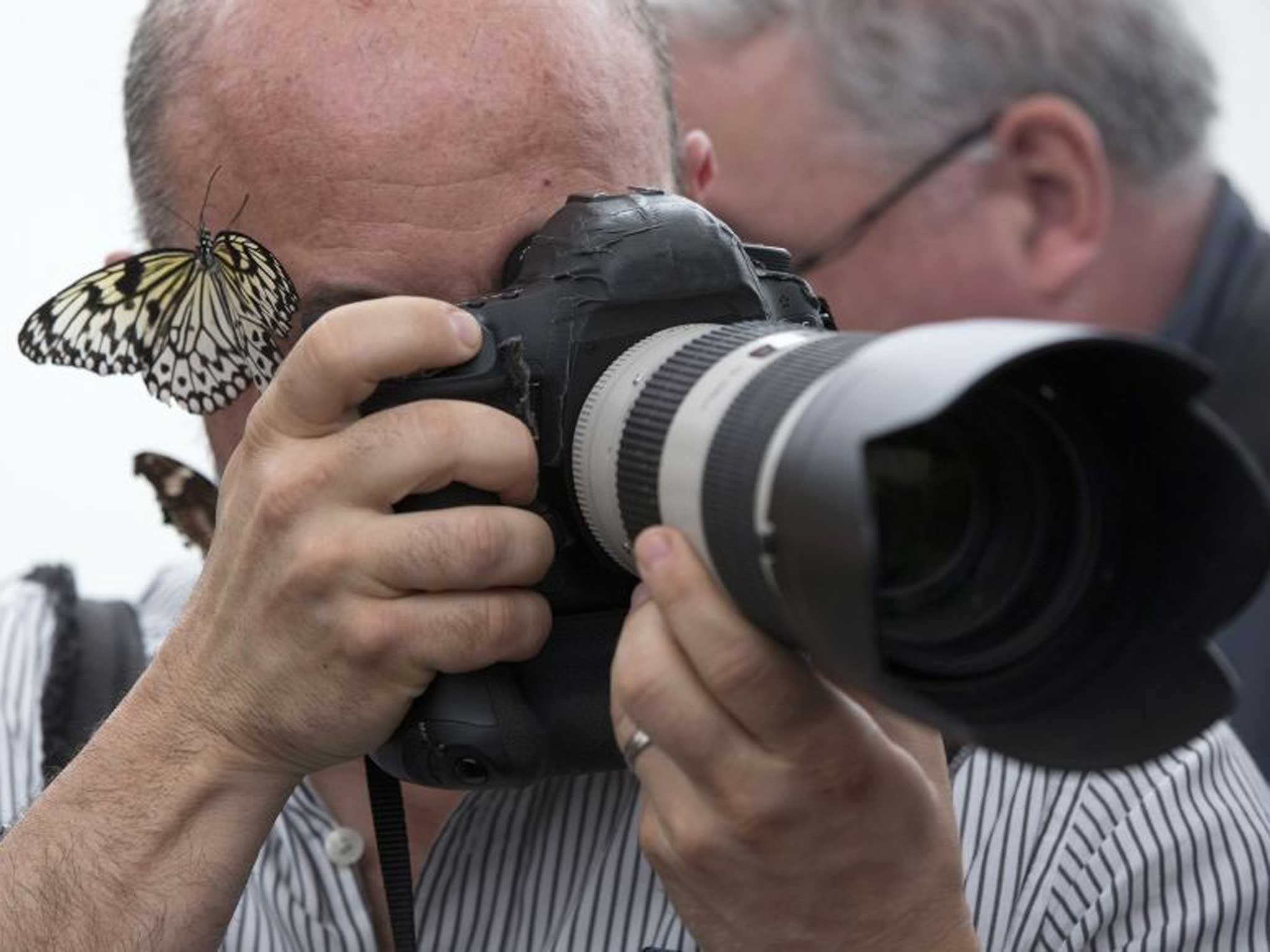

Your support makes all the difference.It was once the definitive image of the British scientist: the intrepid expert armed with his magnifying glass and encyclopaedic knowledge, who dutifully catalogued and explained all the wonders of creation.

But, with the ageing of the last great generalists, such as Sir David Attenborough, academics warn the all-round naturalist is in danger of becoming as much part of history as the Edwardian gentlemen scientist – and with that comes the risk overspecialisation and key trends and discoveries missed.

To stop this, 17 scientists have signed a call to arms, stating that the present "steep decline" in natural history and the trend for university students to focus on narrow specialisms has "troubling implications for science and society", particularly in areas such as health, food security and conservation.

They write in the latest edition of the journal BioScience that natural history observations help fight infectious diseases that cycle through different species, identify promising leads for drug discoveries, manage natural resources, and help the fight to protect species and ecosystems. "Direct knowledge of organisms – what they are, where they live, what they eat, why they behave the way they do, how they die – remains vital to science and society," they say.

They list cases where bad policy decisions followed bad scientific advice due to experts no longer seeing the full picture. A US programme to limit forest fires, for example, failed to realise the importance that fire has in the lifecycle and regeneration of many tree species. It resulted in a $1bn-a-year conservation programme having to be introduced to ensure the continued survival of endangered species now threatened by mismanagement.

The collapse of the Bering Sea walleye pollock fishery could also have been avoided if its lifecycle and interaction with other species had been more clearly understood, they write. Similarly, microbiologists can too easily focus on the microscopic, despite diseases such as avian fly Lyme disease, cholera and rabies being linked in their lifecycles to other animals.

Professor Geoff Boxshall, of London's Natural History Museum, agrees that natural history is under threat. Of the total number of science staff at the museum, in 1998 half were working on classifying organisms and their relationships to each other; 15 years later, they were barely a third of the total cohort.

"'Natural history' as a phrase has gone out of fashion," Professor Boxshall said, "but I don't think it became any less important. It's incredibly difficult to get a view of the whole body of evidence on a particular topic. It's natural historians who can draw the evidence together."

The Government does recognise that there is a problem, although no major steps have yet been taken to address it. Last year, the House of Lords' Science and Technology Committee said the situation was "at the point of crisis", and the Environmental Research Funders Forum had previously warned of a "major skills gap".

Nor is it just a British phenomenon. In 1950 a US undergraduate degree in biology required two or more course in natural history. Now it requires none while the amount of natural-history content in text books has dropped by 40 per cent during the same period as fields such as molecular biology, genetics, experimental biology and ecological modelling flourished.

Professor Paul Smith, the director of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, says the reason is largely because funding organisations have favoured more specialised areas over those cataloguing and collecting data for a wide range of species. "Within the UK it's very hard to get funding," he explains, "and the problem is that once the expertise is lost in a country, it's lost for good."

Emerging economies often still priories the area, particularly in Brazil, but, Prof Smith said: "We've seen in the US and the UK a decline. Once upon a time they were a powerhouse for this sort of activity. But that has ceased to be."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments