The lost girls: Thousands of ‘missing’ girls revealed by analysis of UK’s 2011 census results

The disturbing conclusions we report today are drawn from rigorous analysis of official data. Steve Connor explains the background

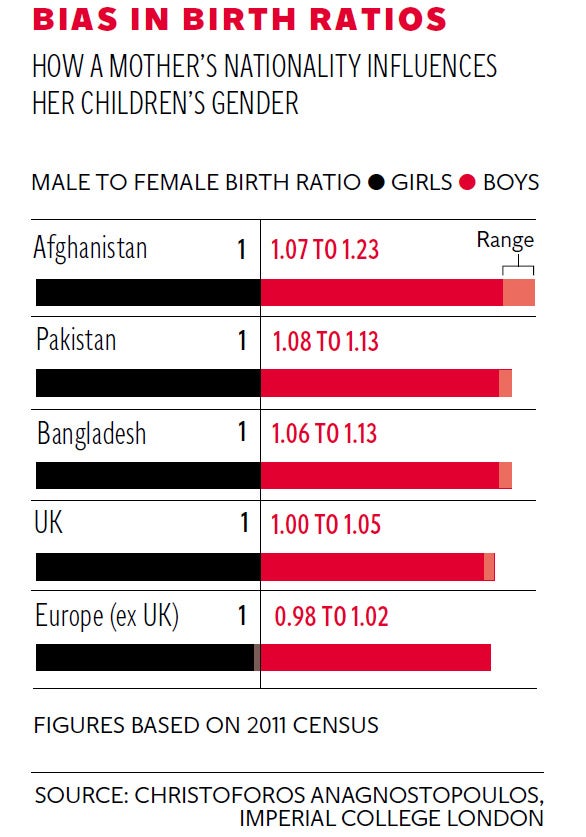

The natural ratio of boys to girls at birth is 1.05, meaning that there are about 105 boys born for every 100 girls – the small balance in favour of boys is seen as nature’s way of counteracting the slightly higher mortality of boys in early life.

When the sex ratio begins to exceed 1.08 – more than 108 boys for every 100 girls – then statisticians believe that some other factor must be at play, such as the selective abortion of female foetuses so that women can become quickly pregnant again with a boy. In some parts of India and China, sex ratios are as high as 1.2 or 1.4 are believed to be caused by widespread sex-selective abortions.

The Independent commissioned data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to see whether sex-selective abortions could be affecting sex ratios within families living in Britain. We used the data to test whether having a daughter as a first child raises the probability of a family’s second-born child being a boy.

All things being equal, the gender of the second child should not be affected significantly by the gender of the first born. However, we found that the sex ratio of second-born children was heavily boy-biased in the families of mothers born in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and that there was some evidence of this being the case in families of mothers born in Bangladesh.

Specifically, we found sex ratios of between about 1.1 and 1.2 for the second child of these families – a heavy bias in favour of boys that could not be explained if the parents were completely “blind” to the sex of their offspring. Overall, the total number of “missing girls” in these families is conservatively estimated to be between 1,400 and 4,700 individuals if you also include sex ratio anomalies for parents born in Nepal and India.

There are two possible explanations for these missing girls and the sex-ratio anomalies seen in two-child families. The first is that it is a statistical feature of the fact that some families with two daughters quickly try for a third child in the hope that it will be son.

This behaviour means that these families quickly move from the two-child category to three-child category, making the two-child category they leave behind more heavily biased toward boys. The idea of “don’t stop until you have a boy” is not as fanciful as it may appear – it was common among the English aristocracy when having a male heir was so important for primogeniture.

The second possibility is gender-selective abortions, notably women aborting female foetuses in the hope of getting pregnant again with a boy. This may well take preference over the “don’t stop” strategy in an age when controlling the overall size of your family is just as important as controlling its gender make-up.

Statisticians from Imperial College tested both scenarios on the data supplied to The Independent by the ONS. They found that the “don’t stop until you get a boy” could in fact explain much of the sex-ratio anomalies seen in the two-child families of parents born in India, China, Nepal and the rest of East Asia.

However it could not explain all of the anomalies seen in the families of mothers born in Pakistan and Afghanistan – and possibly Bangladesh. Put simply, our analysis indicates that gender-selective abortions must be taking place in these communities.

The next question is how much of the gender imbalance in the other ethnic groups (India, China etc) is due to selective abortions? The “don’t stop” behaviour and gender selective abortion are not mutually exclusive, and given that we have found significant evidence of sex-selective abortion among some ethnic groups, it seems reasonable to suppose that it may also play a role in the families of parents born in other countries for which we have weaker statistical evidence.

In total, the statistics suggest that the selective abortion of female foetuses is taking place on a big enough scale to account for between 1,400 and 4,700 “missing girls” within all these ethnic groups (Pakistani, Afghan, Bangladeshi, Indian, Chinese, Nepalese and the others) living in England and Wales.

Being more precise about sex-selective abortions would require a more extensive analysis of census data, combined with birth statistics and possibly the gender of surgically aborted foetuses where this is possible. In any event, it is simply not credible to claim, as Government ministers have done repeatedly, that there is no evidence to suggest that sex-selective abortions take place in Britain.