The lasers fuelling hopes of unlimited, clean nuclear energy

A major engineering milestone in the quest for nuclear fusion holds the promise of a future without energy fears

A milestone has been reached in the 60-year struggle to harness the nuclear reactions that power the Sun in an experiment that could lead to a way of producing an unlimited source of clean and sustainable energy in the form of nuclear fusion.

Scientists in California said on Wednesday night that they have for the first time managed to release more energy from their nuclear fusion experiment than they put into it, which marks a critical threshold in eventually achieving the goal of a self-sustaining nuclear-fusion reaction.

Nuclear fusion uses a fuel source derived from water and produces none of the more dangerous and long-lasting isotopes, such as enriched uranium and plutonium, that result from conventional nuclear power plants, which rely on the fission or splitting of atoms rather than their fusion.

Researchers involved in the Nuclear Ignition Facility (NIF) at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory said that they have used 192 laser beams to compress a tiny fuel pellet less than half the diameter of a human hair in such a way that it triggered the net release of energy by nuclear fusion.

The fuel, composed of the two hydrogen isotopes tritium and deuterium derived from water, was compressed together under enormous pressures and temperatures for less than a billionth of a second, but this was enough to see more energy coming out of the experiment than went into it.

“We are fusing deuterium and tritium, which are isotopes of water, in a way that gets them to run together at high enough speed to overcome their natural electrical repulsion to each other,” said Omar Hurricane of the Livermore laboratory.

“We are finally, by harnessing these reactions, getting more energy out of these reactions than we are putting into the deuterium-tritium fuel... We took a step back from what we tried before and in the process took a leap forward,” said Dr Hurricane, who led the NIF study published in the journal Nature.

There are currently two parallel approaches to nuclear fusion. One uses laser energy to compress fuel pellets -- like the NIF experiment -- and aims to keep the fuel in place by a process known as inertial confinement.

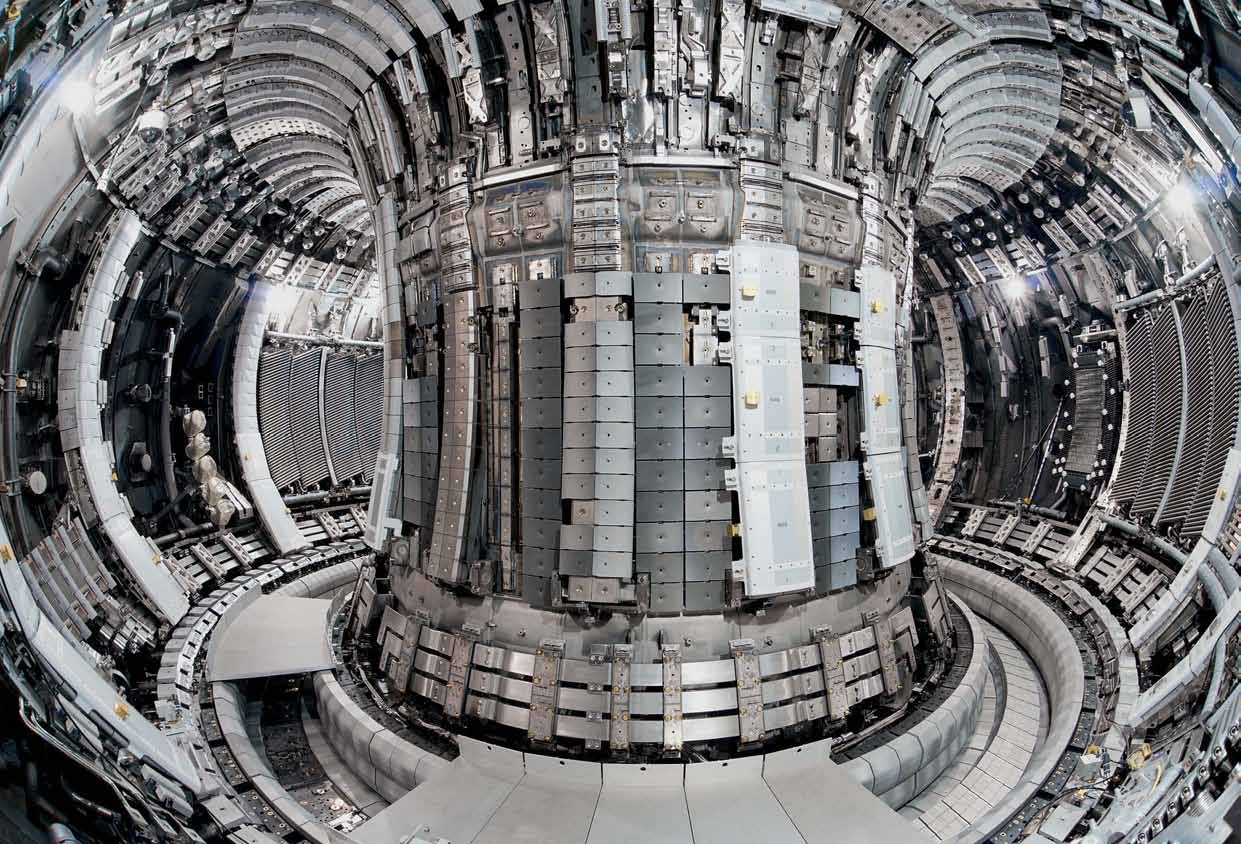

The other approach is to build a complex magnetic “bottle” to hold the hot, electrically charged plasma of the fuel in place. This magnetic confinement is the strategy of the Joint European Torus (JET) experiment in Culham, Oxfordshire, and the international ITER nuclear fusion plant under construction at Cadarache in southern France.

Both approaches aim to gain more energy than is put into the system, and ultimately to a critical stage called “ignition” when the reaction becomes self-sustaining, which would mean that fusion could be exploited practically in power plants as an unlimited source of clean energy.

The breakthrough at NIF was made possible by altering the laser pulses focusing on the fuel pellet in such a way that it led to the even compression of the capsule holding the deuterium and tritium, said Debbie Callahan, one of the researchers involved.

“We had to compress the capsule by 35 times. This is like saying that if you started with a basketball it would be like compressing it down to the size of a pea, but keeping the perfect spherical shape, which is very challenging,” Dr Callahan said.

Professor Steve Cowley, director of the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy, said that the two approaches to nuclear fusion are beginning to make significant headway after decades of painstakingly slow research.

“We have waited 60 years to get close to controlled fusion, and we are now close in both magnetic and inertial-confinement research. We must keep at it,” Professor Cowley said.

“The engineering milestone is when the whole plant produces more energy than it consumes – ITER, the successor to JET, will be the first experiment to do this. ITER is going slowly but progress is happening,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments