The computer will see you now... the cancer prediction software that's better than a doctor

Mathematical formulas can outperform doctors in forecasting patients’ responses, study claims

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Doctors may begin regularly using computer predictions in judging how to treat cancer patients after scientists constructed mathematical formulas that outperformed human experts in forecasting how sufferers will respond to treatment.

A computer model of lung cancer made consistently better predictions of the future symptoms suffered by a set of patients undergoing radiotherapy or chemotherapy than the doctors who actually treated them, scientists said, in a study that demonstrates the increasingly important role of mathematics in cancer medicine.

Personal medical details and the treatment history of each patient were fed into the computer model, which then gave a better assessment than experienced radiation oncologists of how individuals were likely to respond over a two-year period, researchers said.

“If models based on a patient, tumour and treatment characteristics already out-perform the doctors, then it is unethical to make treatment decisions based solely on the doctors’ opinion. We believe models should be implemented in clinical practice to guide decisions,” said Dr Cary Oberije of Maastricht University Medical Hospital in The Netherlands.

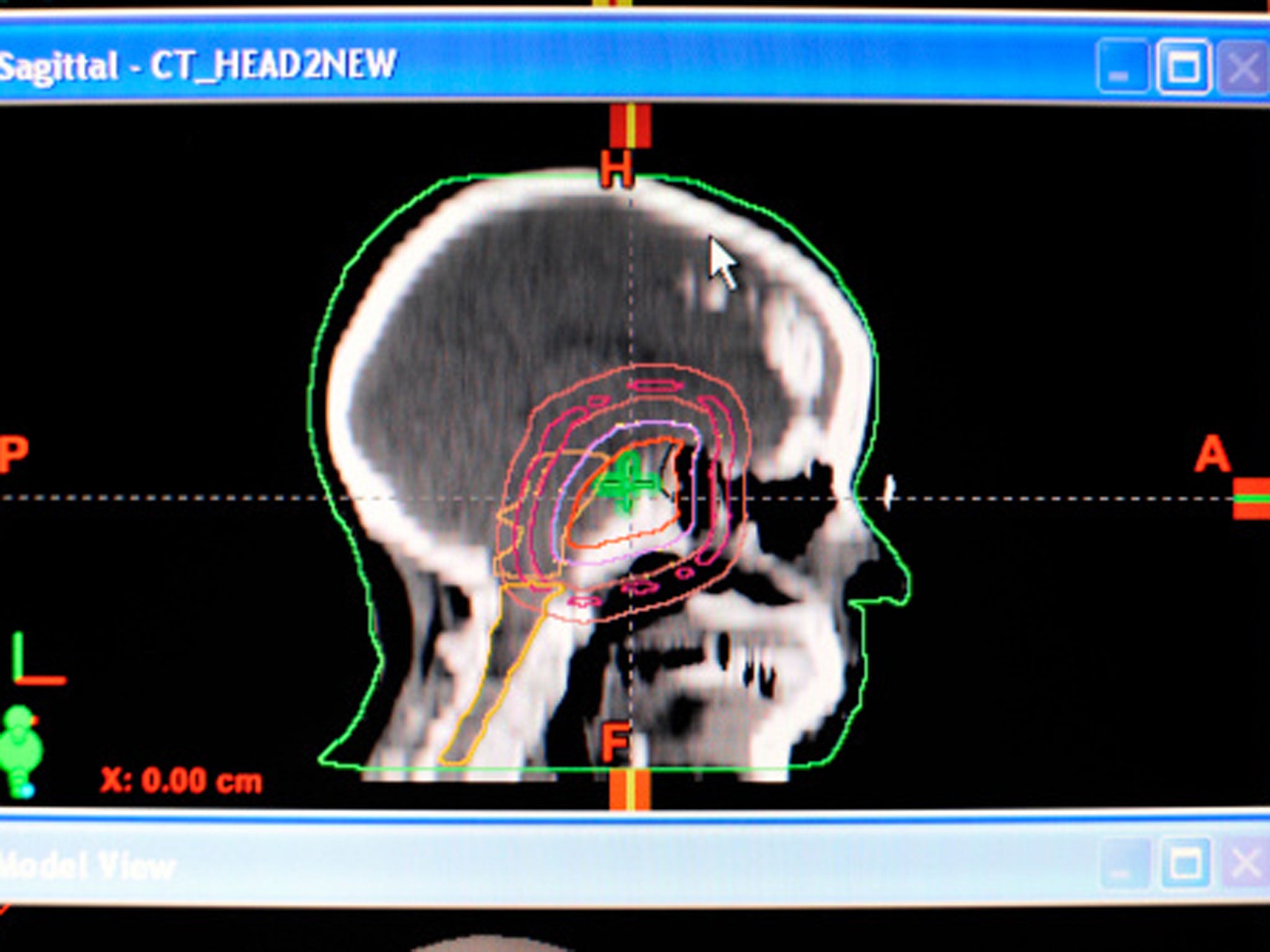

Computer models and the mathematical analysis of cancer data is becoming increasingly important as more and more data is collected on individual patients, whether it is information from sophisticated computer scans or data on a person’s genetic makeup.

Researchers have also shown that cancer tumours differ from person to person and so require different treatments depending on a person’s genes and the type or stage of each individual’s cancer – a process that also requires complex mathematical analysis.

Dr Oberije and colleagues used their mathematical model to make predictions of how many lung cancer patients in a group of 121 would still be alive after two years, how many will suffer breathing difficulties and how many will find it difficult to swallow.

For all three outcomes the model proved significantly better than the patient’s own doctors at making the correct prognosis, with the doctors’ predictions being little better than those expected by chance.

“In our opinion, individualised treatment can only succeed if prediction models are used in clinical practice. We have shown that current models already outperform doctors. Therefore, this study can be used as a strong argument in favour of using prediction models and changing current clinical practice,” Dr Oberije said.

“We know that there are many factors that play a role in the prognosis of patients and prediction models can combine them all… Our study shows that it is very unlikely that a doctor can outperform a model,” she added.

As well as helping decide on treatment options for patients, good predictions are also important in deciding which patients can be used in clinical trials for new drugs, she said.

“They are not perfect, but neither are humans and models are better than humans. They are a tool to help doctors, not to replace them,” Dr Oberije said.

Professor Alan Ashworth, chief executive of the Institute of Cancer Research in London, said that mathematical modelling and computational science is becoming increasingly important as more and more data is collected on cancer diagnostics and genetics.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments