The Big Question: Has research on embryos produced any significant medical advances yet?

Why are we asking this now?

Reforms to the law governing embryology research being voted on by MPs yesterday and today will determine the direction of research in this area for a generation. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill was drawn to update the existing law, to keep pace with scientific advance and social changes, for the first time since it was introduced in 1990. Gordon Brown described the research at the weekend as a "moral endeavour" that could save thousands of lives.

What has it actually achieved so far?

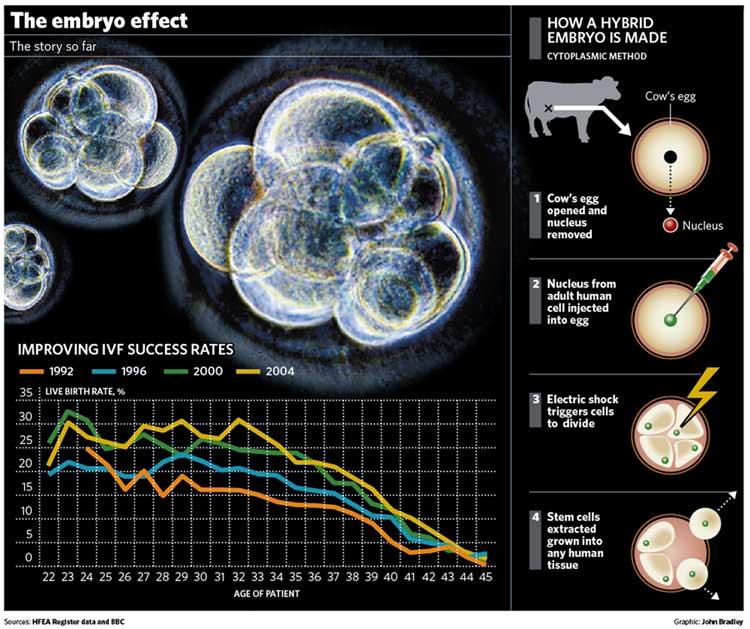

Quite a lot. By far the most important advance has been in the practice of in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) itself. In the quarter century since the birth of Louise Brown, the world's first test-tube baby, in 1978, the technique of creating embryos in the laboratory and implanting them in the womb has come on by leaps and bounds. Two decades ago, success rates for IVF were around 14 live births per 100 cycles of treatment. They improved steadily through the 1990s and are now well over 20 per cent live births, with rates of over 40 per cent in younger age groups in some clinics. However, almost four patients are still disappointed for every one that goes home with a baby, so there is still a lot further to go.

How was it done?

By experimenting on human embryos, altering the culture medium in which they grow in the laboratory, learning how to spot healthy from unhealthy embryos, exploring new techniques for inserting the fertilised embryos back in the womb and inducing them to implant. Different drug regimes have been tried to stimulate egg production by the woman, prior to extraction and fertilisation, and different techniques used to achieve fertilisation, either in the laboratory or in the womb.

What has this meant for women?

A great deal. Thirty years ago, if an infertile woman could not be treated with surgery or drugs, that was the end of the road – they had to resign themselves to adoption or childlessness. Today, around 10,000 babies a year are born by IVF. Around the world, almost one million babies have been born to infertile couples who, but for scientific advance, could never have been conceived.

What about men?

Until the mid-1990s, if a man had a low sperm count, he could not become a father. The only option was to use sperm donated by someone else, to produce a baby that would have a genetic relationship with its mother but not her partner. Now, thanks to research on eggs and embryos, scientists have perfected the technique of injecting individual sperm directly into the egg with a treatment known as ICSI (Intra Cytoplasmic Sperm Injection). Even in a man with a very low sperm count, IVF specialists can find enough sperm to perform ICSI. Around a quarter of all IVF treatments are done using ICSI because of the man's infertility.

Has embryo research benefited children?

Yes, in the sense that it is now possible to ensure that couples with inherited conditions do not pass on their defective genes to their offspring. This is achieved by genetic testing of the embryo in the laboratory to select a "healthy" one to implant in the womb. It is now possible to screen for about 200 inherited conditions, including Huntingdon's disease and the commonest form of cystic fibrosis, by removing a single cell from the developing embryo and testing it. Doctors argue this is improving on nature, not distorting it, but charities for disabled people say it is creating a society in which only perfection is valued.

Can existing children benefit from it?

Yes, by producing "saviour siblings", embryos selected because they are a tissue match for an existing child who may be sick with a disease such as leukaemia and who needs a transplant of stem cells from a matched donor. Once born, blood taken from the umbilical cord of the "saviour sibling", which is a rich source of stem cells, can be "transplanted" to the sick child to cure the disorder. If the cord blood has too few stem cells, the bone marrow provides an alternative source with the saviour sibling acting as donor. The lives of a number of children have been saved in this way, but the issue is one of the three most contentious elements in the Bill and MPs will vote on whether to ban it today. Critics say children should be wanted for themselves, not in order to save another.

Why do we hear so much about stem cell research?

This is the new scientific frontier that embryology research has opened up. In the early stages of development, embryos consist of stem cells capable of developing into any tissue or organ in the body – brain, muscle, liver. Scientists believe that by exploiting this mechanism they may be able to cure conditions such as Parkinson disease, by growing new brain cells from the stem cells. But the research to develop the technique is hampered by the shortage of human eggs.

Where did hybrid embryos come in?

To overcome the shortage of human eggs, scientists proposed using eggs from cows or rabbits as a substitute, only for research. The nuclei of the cow or rabbit's egg would be replaced by nuclei from adult human cells and the resulting hybrid grown for up to 14 days to produce embryonic stem cells.

The goal of the research is to refine the technique so it could ultimately be used with human eggs to grow stem cells used in the treatment of Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and similar diseases. This was the subject of last night's Commons vote.

What has stem cell research using hybrid embryos achieved?

The first animal human hybrid embryos were only created last month by a team at Newcastle University, so it is too early to say. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority licensed the research last January, after seeking approval from the Government. The scientists merged a human nucleus with a cow's egg whose nucleus had been removed to produce an embryo that was 99.9 per cent human. In doing so, the scientists established "proof of principle" that the creation of such hybrid embryos is possible. They said they hoped ultimately to grow such embryos for up to six days and extract embryonic stem cells from them, that could ultimately be used in the treatment of disease. That was before last night's Common's vote.

Has embryo research yielded significant medical benefits?

Yes...

*It has helped women with a near doubling of success rates for IVF bringing the joy of parenthood to thousands more couples.

*It has helped men with development of sperm injection directly into the egg helping thousands more become fathers.

n Children have been helped by preventing genetic disorders being passed down, and in providing tissue donations for sick siblings.

No...

*It has not yielded any cures for diseases such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's or Huntingdon's – so far.

*Progress towards this ultimate goal is likely to be slow, controversial and marked by repeated setbacks and disappointments.

*There is no certainty that the technique of growing and extracting embryonic stem cells as a treatment for disease will work.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments