Mind-reading rodents: Scientists show 'telepathic' rats can communicate using brain-to-brain

Scientists also claim wires connecting one rodent to another can allow communication spanning continents via the internet

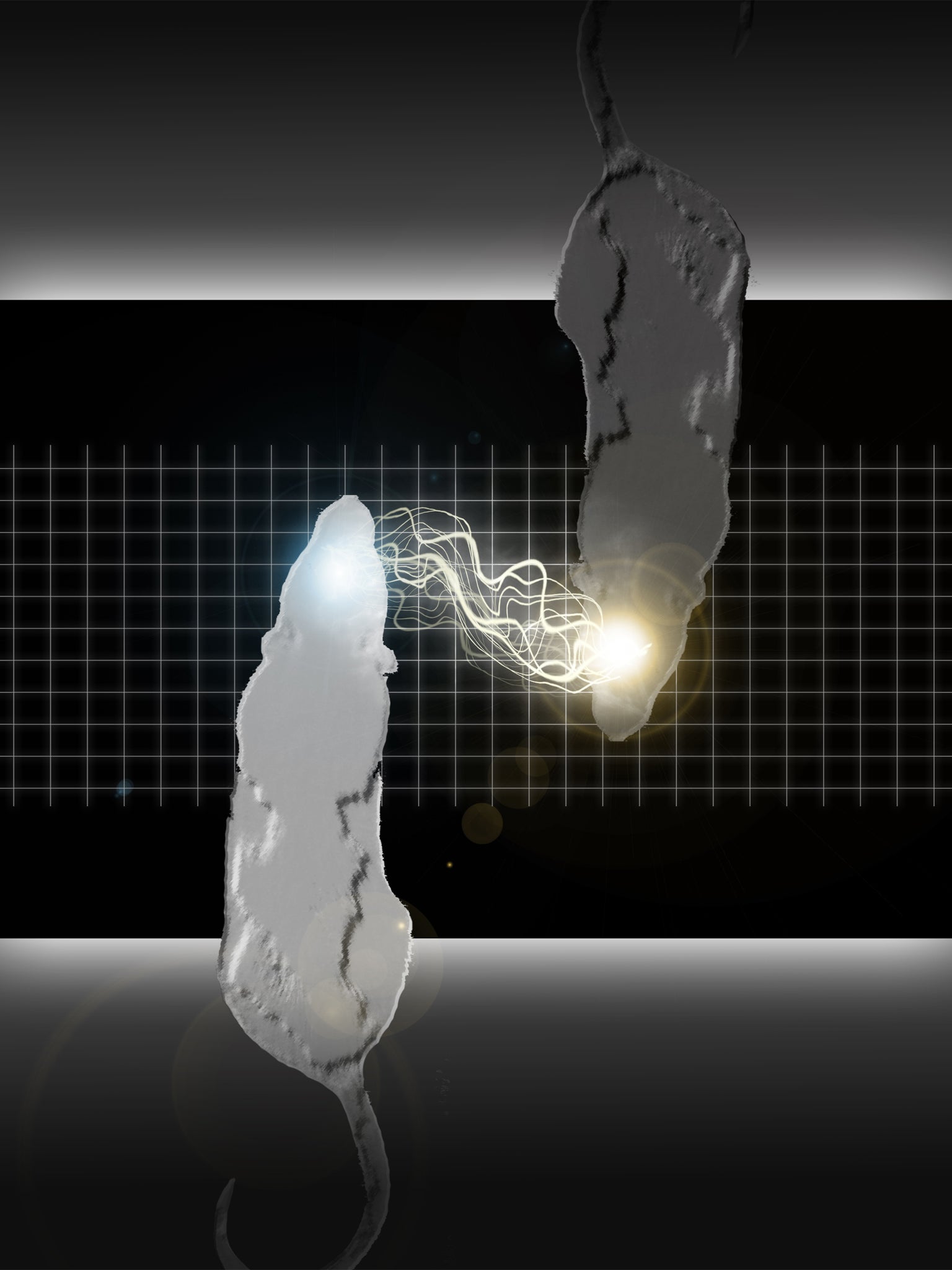

Scientists have shown that it is possible to transmit instructions from one animal to another by a telepathic-like process of brain-to-brain communication.

They believe it is the start of what they are calling “organic” computing based on networks of interconnected brains.

Pairs of laboratory rats have communicated with each other using microscopic electrodes implanted into their brains. One rat was able to pass on instructions to the other rat in a separate cage using a system of electronic encoding.

Brazilian and American scientists say in their study published today that the telepathic-like breakthrough represents an important advance in establishing new ways of communicating between individuals using brain power alone.

“As far as we can tell, these findings demonstrate for the first time that a direct channel for behavioural information exchange can be established between two animal’s brains without the use of the animal’s regular forms of communication,” they say.

One rat in each pair, the “encoder”, detected the physical signals of where to find a food reward and pass on these instructions to the second “decoder” rat, which was able to use the encoded signals of the first rat to find a similar reward in its own cage without any further help.

The scientists also showed that the direct brain-to-brain communication, carried by fine wires connecting one rat to the other, can be extended over the internet, with rats in Brazil communicating with rats in North Carolina, some 7,500km away.

“These experiments showed that we have established a sophisticated direct communication linkage between brains…so, basically, we are creating what I call an organic computer,” said Professor Miguel Nicolelis of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, who led the team.

“We cannot even predict what kinds of emergent properties would appear when animals begin interacting as part of a brain-net. In theory, you could imagine that a combination of brains could provide solutions that individual brains cannot achieve by themselves,” Professor Nicolelis said.

Earlier this month, Professor Nicolelis revealed that he had given laboratory rats a “sixth sense” by connecting up their nervous systems to a sensor that can detect infrared light, which is normally invisible to rats as well as humans.

The latest study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, focussed on using the electrical signals detected in a region of the rat’s brain involved in making decisions when trained to respond to certain stimuli, such as a light in their cage.

Professor Nicolelis inserted micro-electrode implants into the rats’ brains to record the nerve activity associated with making a decision. He then put these signals through a computer encoder which transmitted them via wires to the second rat, which quickly learned how to decode them for its own use.

Each rat was trained to find water in its cage based on the type of signals they were given. However, during the experiment only the encoder rat was exposed to these signals and it had to pass on the right instructions to the second, decoder rat which managed to find the reward in about 70 per cent of cases.

Intriguingly, the scientists found that when the two rats were paired up they quickly established a rapport involving a kind of sensory feedback. If the second rat failed to find the reward, the first rat would modify its brain signals to help out as it too wanted the reward to be found.

“We saw that when the decoder rat committed an error, the encoder basically changed both its brain function and behaviour to make it easier for its partner to get it right,” Professor Nicolelis said.

“The encoder improved the signal-to-noise ratio of its brain activity that represented the decision, so the signal became cleaner and easier to detect. And it made a quicker, cleaner decision to choose the correct lever to press,” he said.

“Invariably, when the encoder made those adaptations, the decoder got the right decision more often, so they both got a better reward,” he added.

Professor Christopher James of the University of Warwick, who has conducted similar research, said that the technique is still very crude and relies on monitoring the nerve activity of just one part of the rat’s brain.

“Leap into the future by, say, 50 years: if you could stimulate many multiple sites, and if we knew what patterns to use and when, then we may well be able to conjure up complex ‘thoughts’,” Professor James said.

“Abstract thoughts are harder to read and represent; but not impossible technologically. We can already do that … we just need to understand the brain better,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments