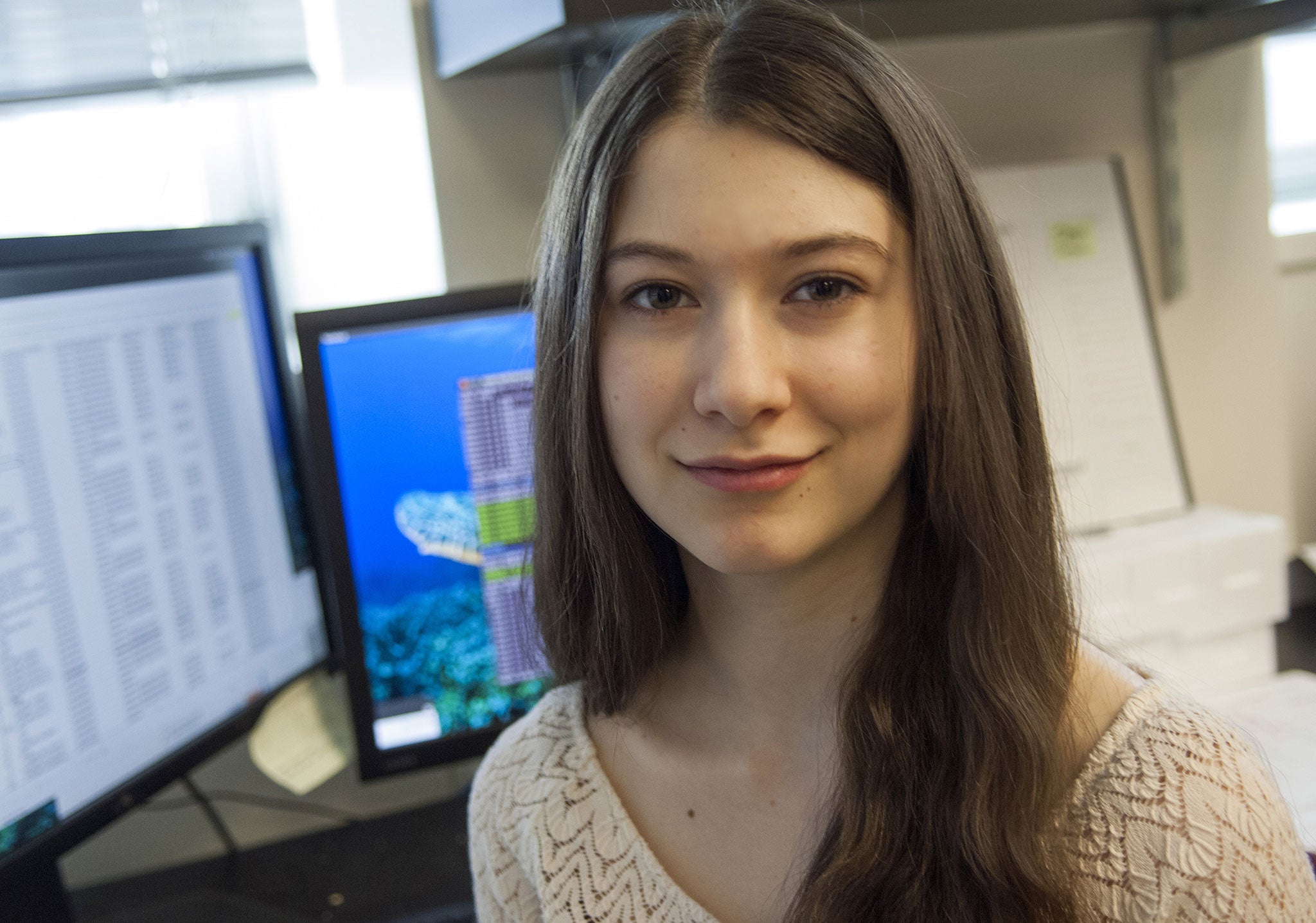

Teen cancer survivor Elana Simon helps scientists study her own rare disease

The eighteen-year-old helped scientists discover a gene flaw that could play a role in how the tumour strikes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A teenager who survived a rare form of cancer went on to help discover a gene flaw that could play a role in how the tumour strikes.

Elana Simon was diagnosed with Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma, a rare form of cancer which mostly affects adolescents and young adults, when she was 12-years-old.

Surgery is currently the only effective treatment if the tumour is caught in time.

Ms Simon, along with her father, who runs a cellular biophysics lab at the Rockefeller University, her surgeon at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and gene specialists at the New York Genome Center looked at data on genetic mutations in a laboratory studying another type of cancer.

This was then compared with samples of the tumour to identify differences in cells for their study, published in the journal Science.

The team found a break in genetic material that left the "head" of one gene fused to the "body" of another in 15 tumours they tested.

This results in an abnormal protein forming inside the tumour but not in normal liver tissue, suggesting it might fuel cancer growth, the researchers wrote.

At the collaborating New York Genome Center, which genetically mapped the samples, co-author Nicolas Robine said a program called FusionCatcher ultimately zeroed in on the strange mutation.

Ms Simon's father Sanford said other researchers then conducted laboratory experiments to show the abnormal protein really is active inside tumour cells.

What has proven difficult for the study is finding enough tumours to test, as just 200 people a year worldwide are diagnosed, according to the Fibrolamellar Cancer Foundation, which helped fund the research. There is also no registry that keeps tissue samples after surgery.

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health are now advising Ms Simons on how to set up a patient registry, and NIH's Office of Rare Diseases Research has posted on its web site a YouTube video in which Elana Simon and a fellow survivor explain why to get involved.

The study was co-authored by another survivor of that particular form of cancer who did not want to be identified.

Additional reporting by Associated Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments