'Supercharged' GM tests get backing from senior government scientist

Professor Ian Boyd says experiments could be a 'powerful force for good'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A senior government scientist has backed controversial experiments to create “supercharged”, genetically modified organisms, comparing concerns about the revolutionary technique to early fears that nuclear fission would destroy the planet.

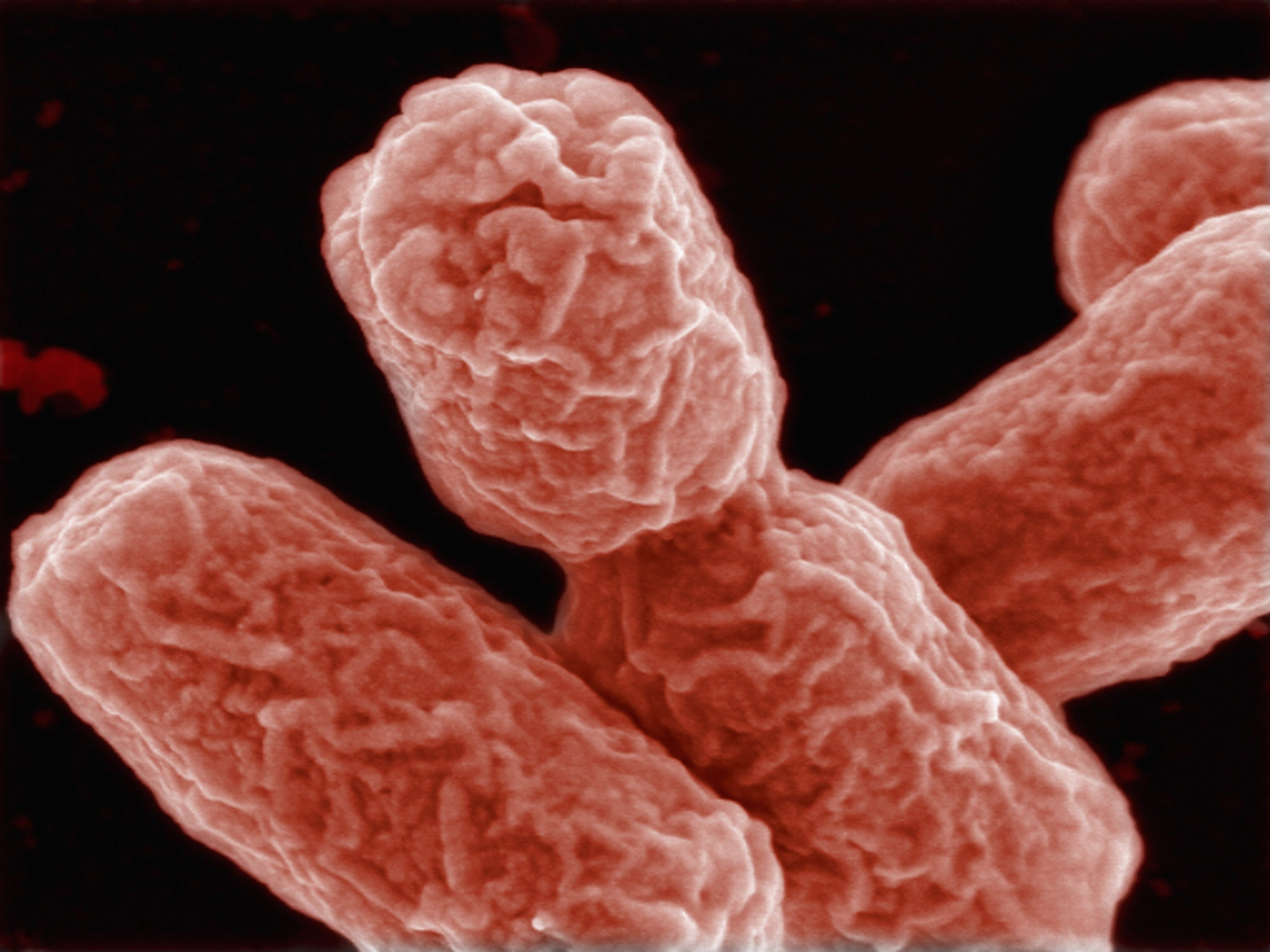

A technology that accelerates the spread of GM genes in fast-reproducing species, “gene drives” could cause havoc if released into wild populations without adequate safeguards, according to some scientists.

But others think their use could, for example, help rid the world of malaria by making mosquitoes unfit to host the parasite that causes the disease. Writing on his blog, Professor Ian Boyd, chief scientific adviser at the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, backed research into the technique, which he described as a potentially “powerful force for good”.

While he admitted that it could also possibly be a “powerful force for bad”, he said there were many reasons why such worries might be misplaced, comparing them to concerns at the dawn of the atomic age.

“Before the first creation of nuclear fission in the laboratory, some theorists thought that creating such a chain reaction could result in the Earth’s destruction because they weren’t sure how it could be contained,” Professor Boyd wrote.“This was an extreme case of an innovation that carried a risk, but all innovations are like this to greater or lesser extents. Innovation is about stepping into the unknown.

“In the case of nuclear fission, the probability of the chain reaction becoming global was assessed as extremely low, but people’s appetite for risk is changing.”

He said gene drives could only be used in organisms that reproduce sexually – ruling out their use in viruses and bacteria – and it would take “hundreds or perhaps thousands of years for the genes to spread” in long-lived creatures like humans, albatrosses and elephants.

He also pointed out that they can occur naturally.

“Like the nuclear fission that brings the UK about one-third of its electricity, genetic-engineering technologies are now a part of our everyday existence,” he said.

“Used wisely, they could be a powerful tool for the rapid spread of beneficial traits through populations of organisms, for example to render wild mosquitoes incapable of transmitting deadly diseases such as dengue fever and malaria,” Professor Boyd said.

But Dr Helen Wallace, of not-for-profit group Genewatch UK, which monitors GM technology, warned there was some evidence that diseases might evolve to become more virulent in response to the use of gene drives designed to act against them.

“It’s clearly a technology that carries many risks, so we would want to be reassured these broader impacts – such as the evolution of viruses – could be properly considered in any regulations,” she said.

“I think it is worrying that Ian Boyd is somewhat dismissive of these issues in his blog, when a lot of scientists have raised very serious concerns,” Dr Wallace added.

The technology: Gene drives

These rely on a “cassette” of gene-editing DNA being inserted into one chromosome before it jumps to another, resulting in the spread of a GM trait in a fast-reproducing species living in the wild.

Some scientists fear this could be misused by rogue states or terrorist groups with access to a genetics lab to create GM super-organisms that could spread in the wild and threaten human health or economically important crops.

Other scientists fear that introducing gene drives into insects or other organisms in the wild for a beneficial purpose could simply lead to unintended, harmful consequences which cannot be predicted.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments