Steve Connor: How can Britain turn learning into lucre?

Lab Notes

Turning science into hard cash is not easy, yet this is what Britain must do if it is to compete in the international knowledge economy.

This is essentially what the Government is being told by some of Britain's leading scientific organisations lobbying on behalf of science in the forthcoming review of public spending.

Science and engineering, they argue, are the fundamental basis of a modern, knowledge-based economy. We need, as a country, to invest heavily in these areas if we are to produce the scientists and engineers who will lead our economic revival. But how to turn the raw scientific achievement of academia into the innovative products or services that people want and need?

Successive governments have tried to tackle this issue, with varying degrees of success. One way is to encourage closer contact between the best scientific minds in our universities and the innovative acumen of the brightest business brains. This has not been an easy task when many academics have traditionally seen business as an activity not far removed from devil worship, and business has often looked upon academia as an ivory-towered irrelevance.

I've just spent a few days in Edinburgh, a city with a rich history of science and innovation. Its latest approach to bridging this ancient divide has crystallised into an organisation called the Edinburgh Science Triangle, comprised of government, academia and business. Its aim is to bring university scientists and business leaders together, with the help of a little lubrication in the form of funding from government and the EU.

"Wherever you go in the world, people are trying to develop a knowledge economy," says its project director, Barry Shafe. " There are more than 500 promotion agencies out there. When you are a small nation and you are up against that, you have to focus and you have to differentiate. We cannot possibly expect to be world leaders in every area."

Edinburgh, and Scotland as a whole, has punched well above its weight in terms of scientific innovation – ever since the days of Greenock-born James Watt and his steam engine. One of the best recent examples is the first genetically engineered vaccine against the hepatitis-B virus, and an associated diagnostic kit, developed by Edinburgh University's Professor Ken Murray in 1980. The rights to this technology were licensed to Biogen, a US biotechnology company, and the royalties generated some £40m. The university received its first $1m royalty cheque just nine years after the licence agreement was signed.

How much better it would have been for the wider economy if there had been a British company big enough and bold enough to make this manufacturing investment. This comes down to one of the main reasons why America still does better in science innovation than Britain: it is a big place, with lots of money and a culture of taking the sort of financial risks that pay off in the long term.

Edinburgh is fortunate in its science base. It has an excellent record in computer science, notably artificial intelligence and computer vision, and of course its biological sciences has been world class – the Roslin Institute on the outskirts of the city was where Dolly the sheep was cloned.

The same, however, can be said of many other UK university cities, and not just those within the London-Oxford-Cambridge triangle. In my experience, university scientists have never been more willing to get involved with the process of developing research ideas for the wider market. The real barrier has been a reluctance of the finance houses in Britain to translate those ideas into the earliest stages of pre-product development. In the US, there is far less reluctance to finance so-called translational research, and this is why America does so much better than Britain at turning science into cash.

*****

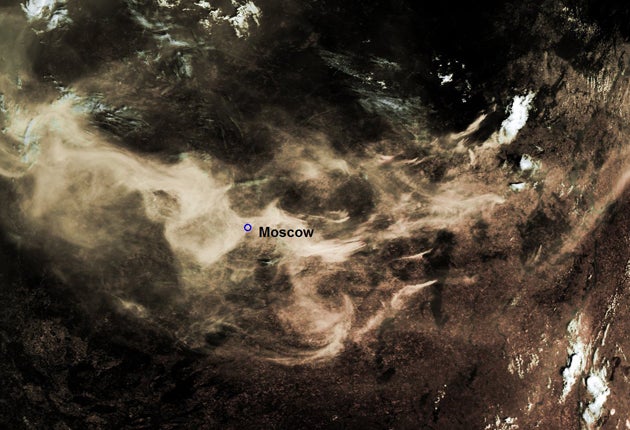

Seeing the smoke billowing over Moscow and the effect of the wildfires on the Russian countryside reminded me of two experiences in that country that puzzled me. One was in Siberia in mid-summer when I saw people casually set fire to grass in a local park; the other was in a Moscow suburb when, again, grass was left smouldering by railway embankments, apparently deliberately lit by locals.

I asked a travelling companion what was it all about and the only explanation she could offer was that some Russians believe it is important to set fire to grass to " purify" or "renew" the soil. I don't know how many of the fires raging across the parched Russian landscape were lit deliberately for this reason, but this habit does seem to lack solid scientific basis.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments