'Social dispersion': the Facebook factor that predicts relationships - and when they will end

Scientists examine 1.3 million Facebook users to show how mutual friends (and friends of friends) play a part in keeping couples together

A scientific paper authored by a computer scientist and a senior engineer at Facebook has shown how your online social networks not only reveal who you’re going out with, but also when you’ll break up (and yes, that's without checking your relationship status).

The study, conducted by Lars Backstrom and Jon Kleinberg, used anonymous data from more than 1.3 million Facebook users to analyse the shape of their friendship networks – looking at how many friends individuals had in common, who was friends with their friends, and so on and so forth.

Their data set looked at users aged 20 years and up, selecting those who described themselves as in a relationship and had between 50 and 2,000 friends. This meant crunching through around 379 million nodes and 8.6 billion individual links – a pretty substantial body of evidence.

Backstrom and Kleinberg found that looking at just the number of mutual friends between any two individuals – a factor known as ‘embeddedness’ - was not actually a strong indicator the pair were in a relationship, and that instead a quality known as ‘dispersion’ was far more telling.

Dispersion measures not only mutual friends but the network structures that connect these friends together. ‘Low dispersion’ – the quality that was associated with couples – indicates not only that two people have a large number of mutual friends, but also that these mutual friends knew one another.

Essentially, romantic partners act as social bridges between individuals’ networks, introducing people to each other and creating friendships. Eg, you might go for drinks with your boyfriend's friends from work and bring some of your friends from home to meet them.

Using this dispersion algorithm Backstrom and Kleinberg were able to correctly identify who somebody’s spouse was 60 per cent of the time and correctly guess somebody’s partner a third of the time – a far better return than the 2 per cent success rate from pure guesswork.

This seems to make sense given that the dispersion between a couple’s friends is likely to decrease over time as social functions gradually introduce the pair’s social networks to one another.

However, the study also found that they could predict with some accuracy whether or not couples were likely to break up. Relationships that hadn’t been spotted using the dispersion algorithm were 50 per cent more likely to break up over the next two months (the time period examined by the study) compared to those that had been identified by looking at friendships of mutual friends.

This seems to suggest that long-lasting relationships tend to involve a lot of social interaction between individuals' networks - though this is by no means definitely causative.

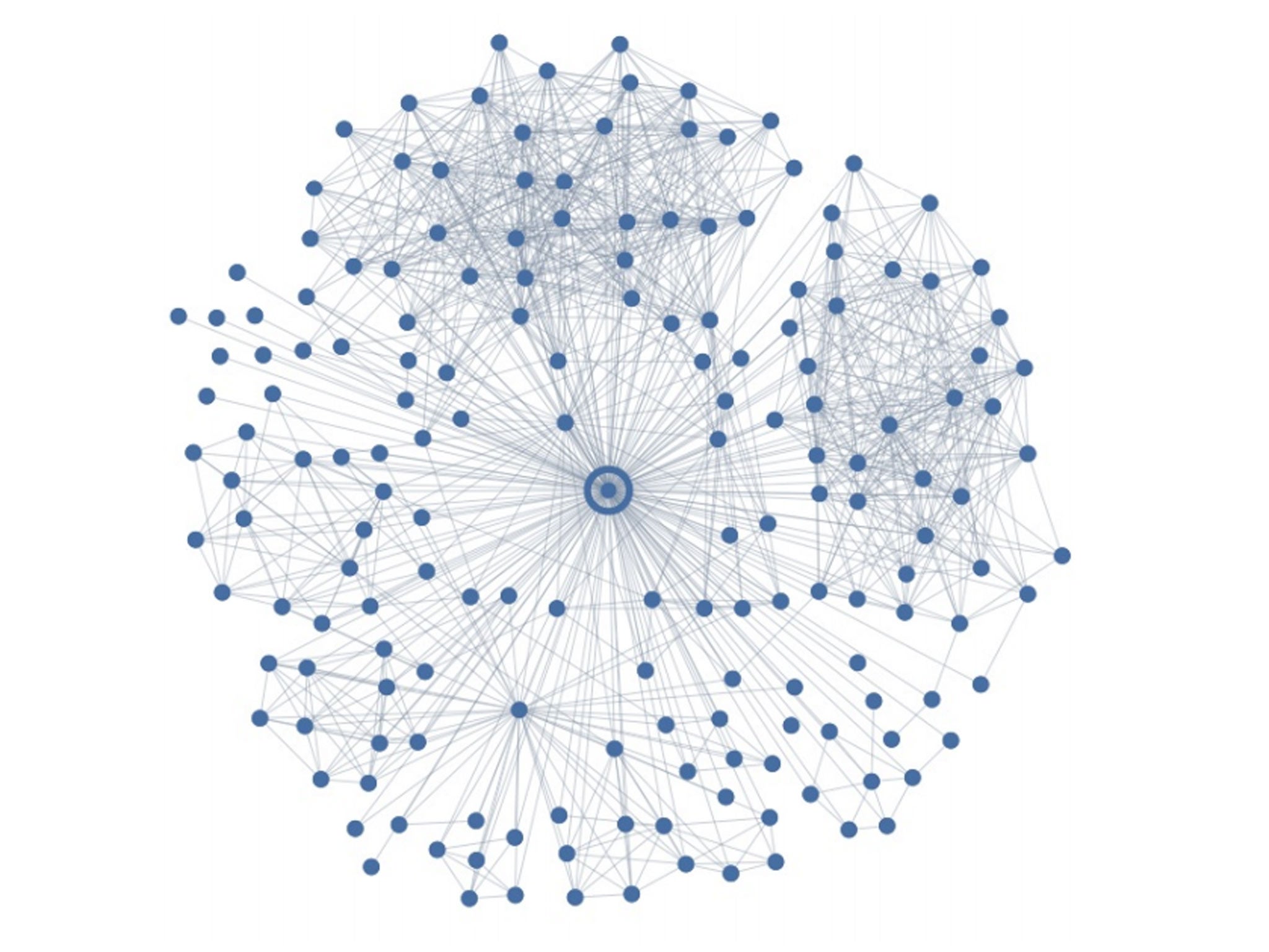

An illustration of an individual's network. The central node is the user, with the cluster at the top representing friends from work and the cluster on the right showing friends from school.

The node at the bottom left is the individual's spouse - showing that he or she is only loosely connected to the other clusters.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments