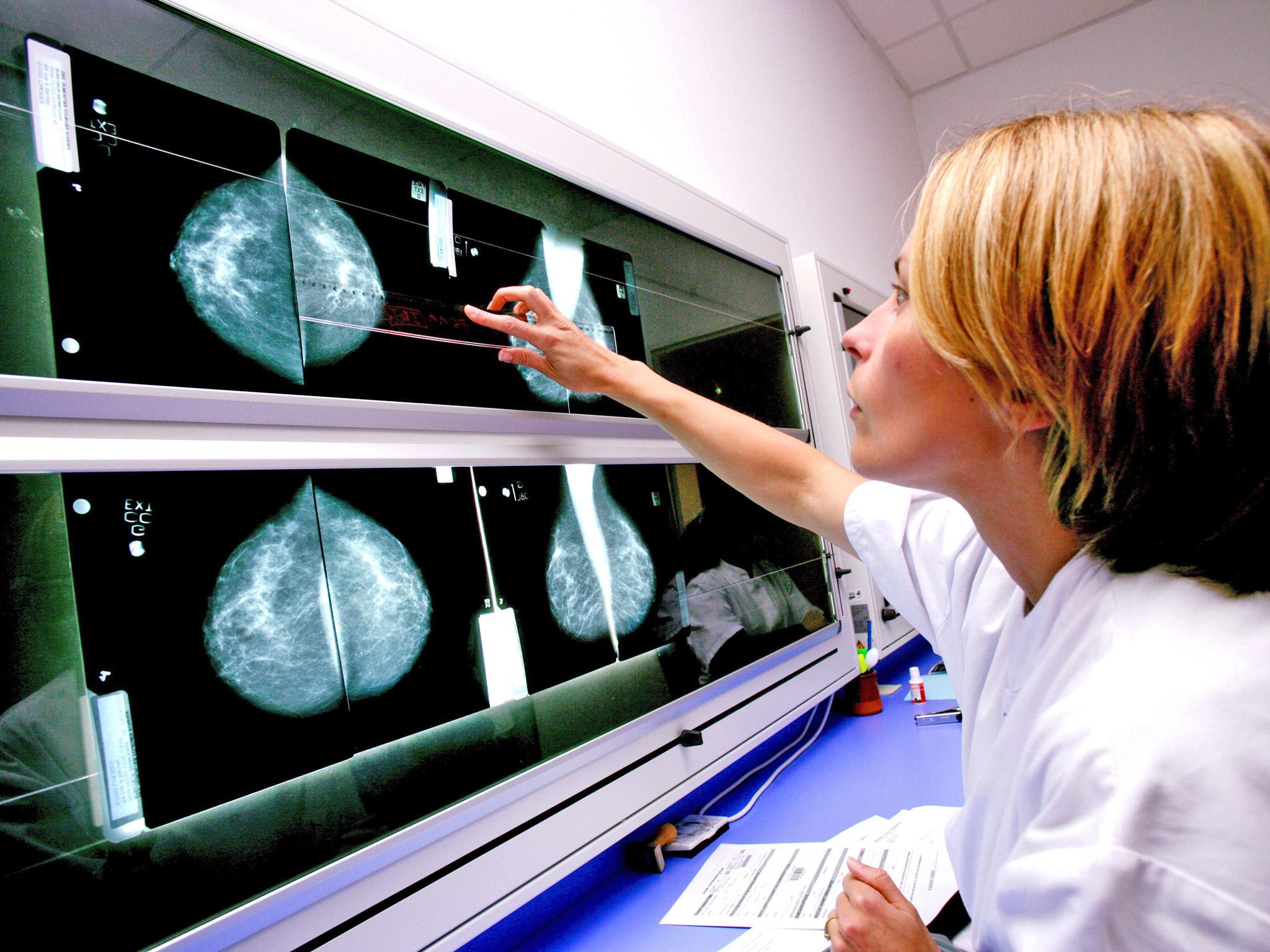

Scientists 'put positive spin' on breast cancer studies

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists involved in breast cancer research tend to exaggerate the positives and underplay the negatives of their findings, a new study suggests.

As a result, patients may be given treatments that are less effective than claimed and with worse side-effects than reported.

In two-thirds of the reports studied, the scientists played down the nastiest side-effects of their trials, especially where the treatments also showed significant benefits.

The team, from Princess Margaret Hospital in Toronto, Canada, say they found no influence from sponsors of breast cancer trials, whether in the drug industry or in academic institutions.

But they note that "the pharmaceutical industry is increasingly influential in clinical trial sponsorship". Over the past 30 years, the number of phase 3 trials (final testing) sponsored by the industry has risen from 24 per cent to 72 per cent, they say.

One explanation for the findings is that scientists want to be noticed, they say. Positive results get more attention than negative findings and are more likely to be cited in the scientific literature, which is important for boosting scientific careers.

Professor Ian Tannock, who led the study, said: "Better and more accurate reporting is urgently needed. Journal editors and reviewers, who give their expertise on the topic, are very important in ensuring this happens."

Richard Francis, research manager at the UK charity Breakthrough Breast Cancer, said: "We strongly believe that making clinical trial data freely available would decrease the potential for 'spin' by allowing more researchers to investigate the results.

"This will ensure trials are accurately assessed by regulatory bodies, allow comparisons with other studies and prevent duplication of trials."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments