Scientists discover world’s oldest cancer has survived – passing from host to host – for 11,000 years

Studying the disease among dogs could allow experts to build a defence if human cancers became transmissible

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have discovered the world’s oldest cancer, which has survived continuously being transferred from host to host since appearing in a single dog 11,000 years ago.

The vast majority of cancers arise from one mutated cell and, if they spread throughout the body, die when the host itself is killed.

But there is a genital cancer in dogs which, with the ability to transfer from host to host through sexual activity, has been able to survive for more than 10,000 years.

It is one of only two such transmissible diseases found in the natural world, and experts at the University of Cambridge said studying it could provide humans with vital defence if other cancers took on the ability to spread between hosts.

The cancer, which causes grotesque genital tumours to dogs around the world, still contains the DNA of the original animal in which it appeared more than 10,000 years ago.

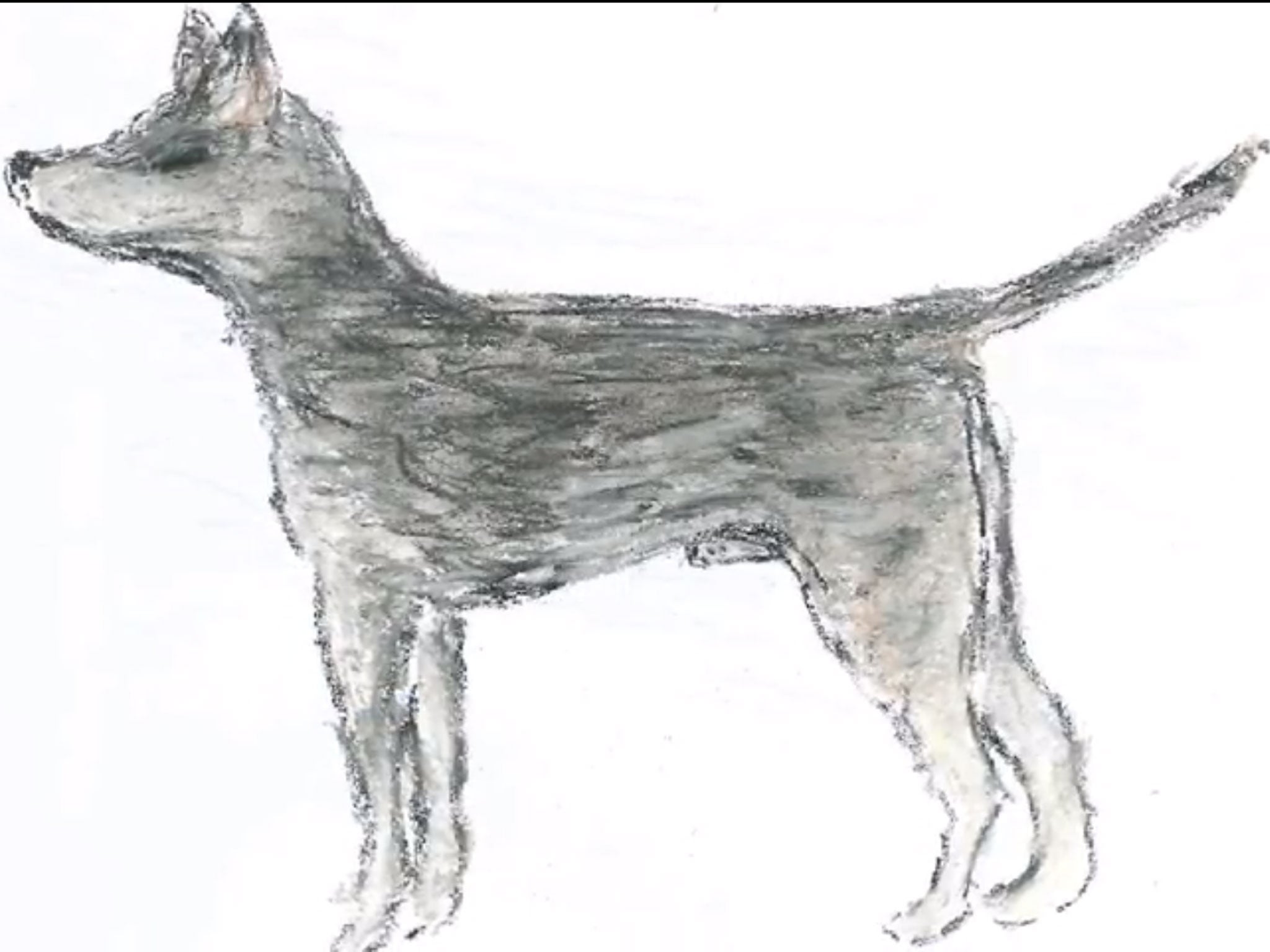

By sequencing the genome of the cancer, for the first time Dr Elizabeth Murchison and her colleagues were able to build up a remarkable picture of this ancient dog – what it would have looked like, and even to some extent how it would have behaved.

Resembling an Alaskan Malamute or Husky, it probably had a short, straight coat that was coloured either grey/brown or black. Its genetic sequence could not determine if it was male or female, but did indicate that it was a relatively inbred individual, the researchers said.

The cancer itself existed in “one isolated population of dogs for most of its history”, Dr Murchison said. Around 500 years ago it started spreading around the world – coinciding with the dawn of the human age of exploration.

“We do not know why this particular individual gave rise to a transmissible cancer,” said Dr Murchison. “But it is fascinating to look back in time and reconstruct the identity of this ancient dog whose genome is still alive today in the cells of the cancer that it spawned.”

Alongside the devastating facial cancer that spreads between Tasmanian devils through biting, the transmissible genital cancer in dogs is the only one resistant enough to survive the process of passing from one host to another.

Whereas a typical cancer in humans carries between 1,000 and 5,000 mutations, the ancient dog cancer has around two million mutations. One type of these, known as a “molecular clock”, accumulates steadily over time and so could be used to date the disease.

The researchers said that the reason the cancer is resistant enough to survive transmittance could come down to one or more of the mutations.

Professor Sir Mike Stratton, a senior author on the project and director at the Wellcome Trust’s Sanger Institute, said: “The genome of the transmissible dog cancer will help us to understand the processes that allow cancers to become transmissible.

“Although transmissible cancers are very rare, we should be prepared in case such a disease emerged in humans or other animals. Furthermore, studying the evolution of this ancient cancer can help us to understand factors driving cancer evolution more generally.”

Dr Murchison’s study, entitled “Transmissible dog cancer genome reveals the origin and history of an ancient cell lineage”, has been published in the journal Science.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments