Scientists develop new malaria drug that treats symptoms and prevents infection being transmitted

Researchers estimated that the new drug could eventually be sold for less than $1 a dose

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have developed a potential new drug against malaria that treats the symptoms, can be given as a single, one-off dose, and prevents the infection being transmitted by mosquito bites to other people.

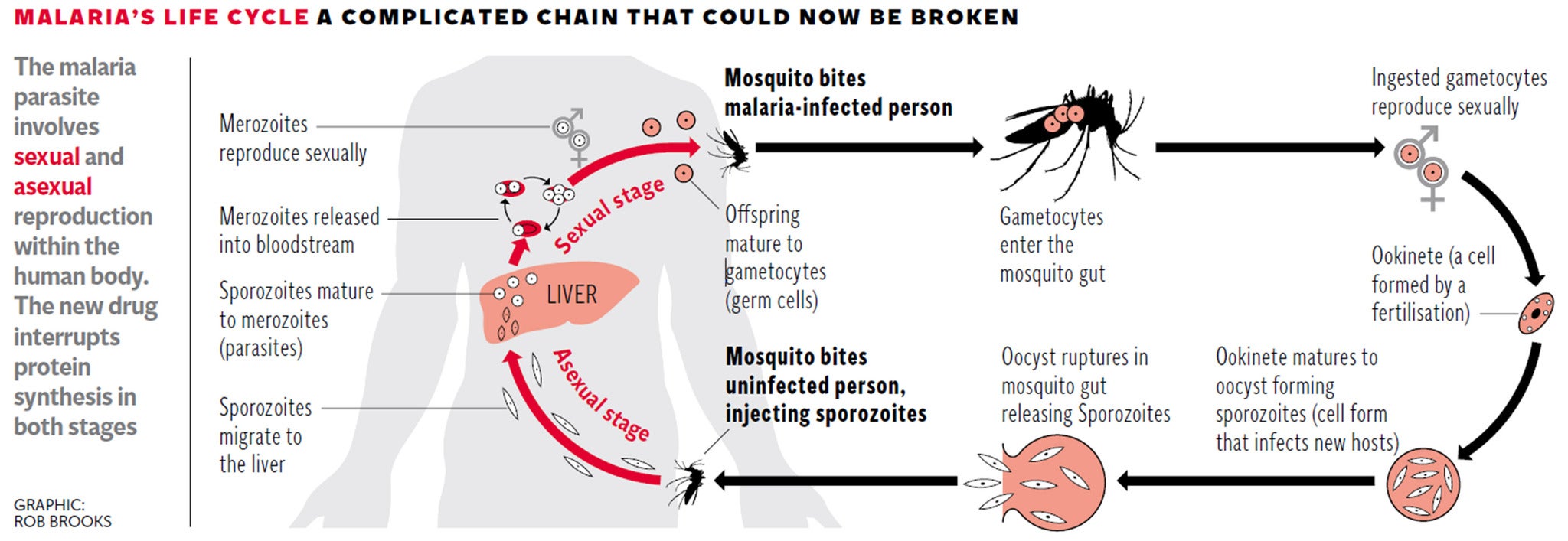

Laboratory tests show that the drug works against the different stages of the malaria parasite’s complex life cycle, which suggests it could be used as a prophylactic treatment to protect vulnerable children and pregnant women against being infected, the researchers said.

The development comes at a time when there is growing drug-resistance against the front-line treatments for malaria, which infects about 200m people worldwide and kills nearly 600,000 individuals each year – mainly children in sub-Saharan Africa.

Researchers estimated that the new drug, which is soon to enter the first phase of clinical trials, could eventually be sold for less than $1 a dose, which is considered the maximum price that the poorest affected countries can afford.

“[It] has the potential to treat malaria with a single dose, prevent the spread of malaria from infected people and protect a person from developing the disease in the first place,” said Ian Gilbert, professor of medicinal chemistry at Dundee University and one of the lead authors of the study published in the journal Nature.

“There are other compounds being developed for malaria but relatively few of have reached the stage we’re at. What’s most exciting is the number of potential attributes, such as the ability to give it in a single dose which will mean that medics can make sure a patient completes the treatment,” Professor Gilbert said.

“It also has the potential to prevent malaria, as a prophylactic. Some people are quite vulnerable to malaria, such as children and pregnant women, and it has the power to block malaria transmission,” he said.

Click HERE to view full-size graphic

The drug, which is known only by its code name of DDD107498, targets a vital protein involved in the conversion of genetic instructions into the enzymes and proteins of the malaria cell. All stages of the malaria parasite need this key protein which is why the drug continues to work at various phases in its life cycle.

Tests on infected human cells in the laboratory and mice that can be infected with malaria, show that the drug blocks the growth and development of both the sexual and asexual stages of the parasite’s life-cycle, clearing it from the blood and liver of infected animals.

“New drugs are urgently needed to treat malaria, a resistance to current gold-standard antimalarial drugs is now considered a real theat,” said Kevin Read of Dundee, a co-author of the study.

“The compound we have discovered works in a different way to all other antimalarial medicines on the market or in clinical development, which mean that it has great potential to work against current drug-resistant parasites,” Dr Read said.

“It targets part of the machinery that makes proteins within the parasite that causes malaria,” he said.

The latest, most effective antimalarial drug is artemisinin, which was original isolated from the sweet wormwood plant used in traditional Chinese medicine. However, in recent years strains of malaria resistant to artemisinin have emerged in south-east Asia.

“These strains are already present at the Myanmar-Indian border and it’s a race against time to stop resistance spreading to the most vulnerable populations in Africa,” said Michael Chew of the Wellcome Trust, which funded the research.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments