Rosetta mission reaches critical point – after more than 10 years in space

Spacecraft will attempt to land a probe on a comet tomorrow

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.More than 20 years after it was first approved, a European space mission reaches a climax when a fridge-sized space-probe gently touches down on a comet travelling at 34,000mph.

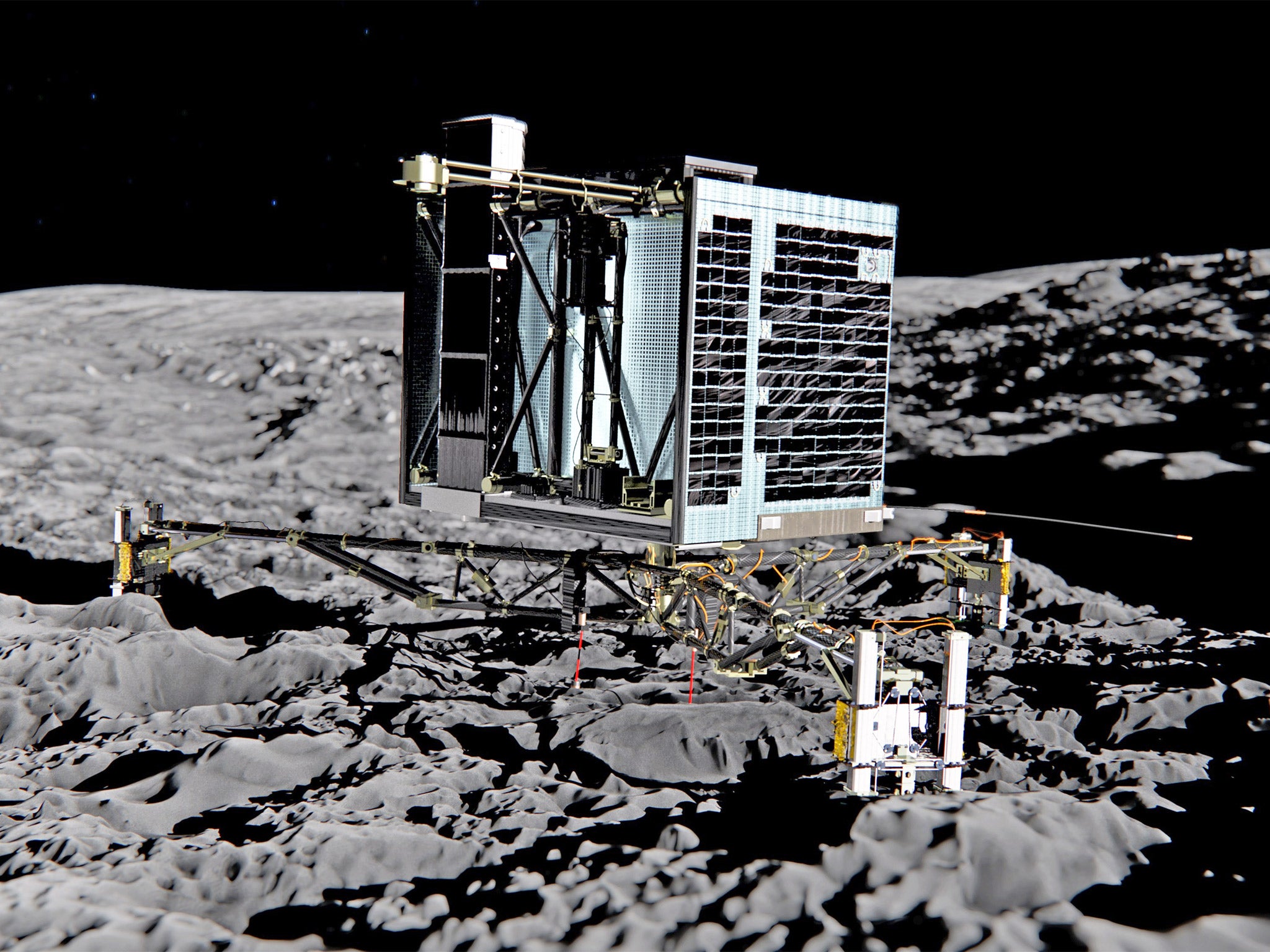

If all goes to plan, the Philae lander of the Rosetta mission should be sending back the first images of the ice surface of comet 67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko’s. It will be the first soft landing on a comet in the history of space flight – a feat likened to throwing a hammer from London and hitting a nail with it in Delhi.

After chasing the comet over a cumulative distance of 6.4 billion km, the European Space Agency’s one billion Euro Rosetta spacecraft has been orbiting its quarry for the past three months.

Now the moment has arrived for Philae to be released from its mothership, so that it can drift at a slow walking pace to close the final gap with Churyumov-Gerasimenko, named after the two Soviet scientists who discovered the comet in 1969.

Click HERE to view full-size version of graphic

It will take Philae about seven hours from the moment of release to cover the remaining 22.5km separating Rosetta from the comet. This means touchdown should occur at about 3.30pm British time, however given that it takes 28 minutes 20 seconds for radio signals to reach Earth, final confirmation will only happen at about 4pm.

“There are a number of things that can still go wrong. Even the decision to separate the lander from Rosetta may be delayed if any failures are detected,” said Rosemary Young, a programme manager on Rosetta at the UK Space Agency.

“Then there’s the landing itself. Nobody knows what’s going to happen. It is supposed to be a soft landing but the Philae lander will have to take the impact on its legs, there are no rocket thrusters involved,” Dr Young said.

“One of its problems will be to stay down. The comet’s gravity is just one hundred thousandth of that on Earth, and if it lands on a slope greater than 45 degrees it will just fall over,” she said.

On touchdown, two harpoons will be fired from Philae to anchor the lander on the comet’s dusty surface. Once these have been hauled in, the feet of the lander’s legs will screw the probe firmly in place.

Comet 67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko orbits the Sun between the orbits of Jupiter and Earth, taking it between about 800 million km and 186 million km from the Sun – part of the “builder’s rubble” left over from the beginning of the Solar System nearly five billion years ago.

Launched in 2004, it has taken Rosetta more than 10 years to reach the comet, following a circuitous journey involving three fly-bys of Earth and one of Mars to use their gravity as “slingshots” to speed the spacecraft’s progress.

Whatever happens to Philae, the Rosetta spacecraft will continue to orbit the comet as it continues its solar orbit. In the coming months, the comet will warm as it approaches the nearest point to the Sun, causing jets of vapour to be released from its nucleus.

If Philae survives the landing, its nine instruments will continue to monitor the gases given off for signs of organic molecules – the building blocks of life. It will also drill into the comet’s frozen surface up to a depth of 20 cm to collect samples for analysis by the lander’s on-board laboratory.

“We can do a certain amount of analysis from a distance, but we cannot see what’s on the surface or what’s below the surface in any great detail. We hope to drill down deep enough to get to the primitive grains below the surface that were around when the comet first formed,” Dr Young said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments