Mysterious giant 2,000-year-old rock artworks depicting ancient rituals mapped in detail for first time

Engravings show how people lived and travelled in the region

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some of the largest rock engravings recorded anywhere in the world have been mapped in detail for the first time by researchers.

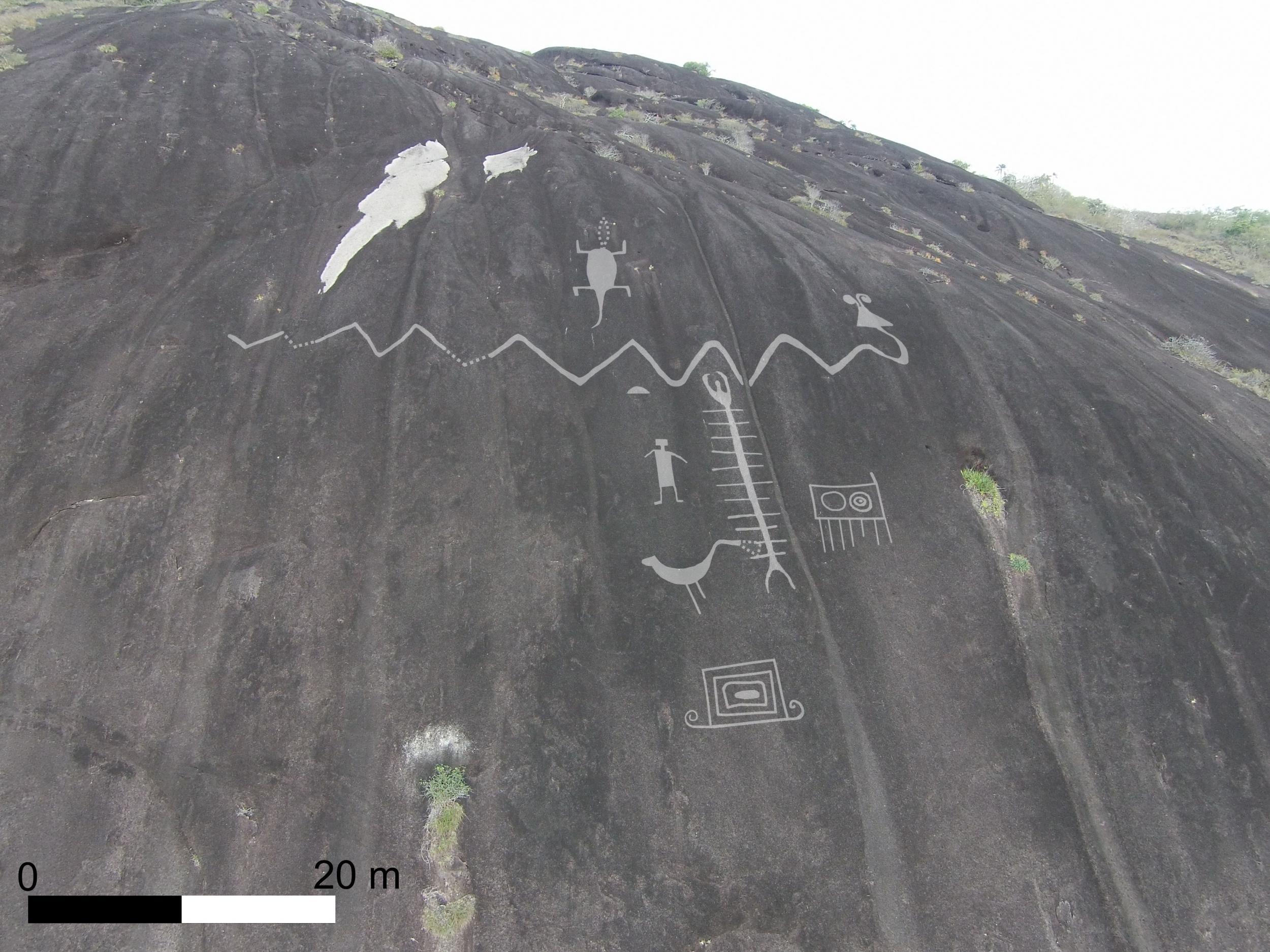

The petroglyphs, scanned by researchers from University College London, depict animals, humans and ancient cultural rituals.

Some of the art, located in the Atures Rapids area of western Venezuela, is believed to be up to 2,000 years old.

One panel, which measures 304 square metres, contains at least 93 individual engravings each stretching several metres across.

An engraving of a horned snake measures more than 30 metres in length.

Using drones, the researchers were able to photograph the engravings, some of which are in extremely inaccessible areas.

Low water levels in the Orinoco River meant more of the art was exposed.

Study author Dr Philip Riris, of UCL’s Institute of Archaeology, said the area was an ethnic, linguistic and cultural convergence zone.

“The motifs documented here display similarities to several other rock art sites in the locality, as well as in Brazil, Colombia, and much further afield,” he said.

“This is one of the first in-depth studies to show the extent and depth of cultural connections to other areas of northern South America in pre-Columbian and colonial times.”

He added the engravings provided a snapshot into ancient lives.

“While painted rock art is mainly associated with remote funerary sites, these engravings are embedded in the everyday — how people lived and travelled in the region, the importance of aquatic resources and the seasonal rhythmic rising and falling of the water.

“The size of some of the individual engravings is quite extraordinary.”

Rock engravings of the Middle Orinoco River have been studied before, but never in this level of detail, which offers researchers new insights into the archaeological and ethnographic context of the art.

Almost all the engravings are affected by seasonally rising and falling water levels in the Orinoco.

Depending on the rain upstream, the relative height of the river also varies annually by up to several metres during the extremes of both seasons.

In one panel, a motif of a flautist surrounded by other human figures probably depicts part of an indigenous rite of renewal.

Researchers believe such performances may have coincided with the seasonal emergence of the engravings from the river before the wet season, when the islands are more accessible and the harvest would take place.

“Our project focuses on the archaeology of Cotua Island and its immediate vicinity of the Atures Rapids,” said principal investigator Dr Jose Oliver.

“Available archaeological evidence suggests that traders from diverse and distant regions interacted in this area over the course of two millennia before European colonisation.

“The project's aim is to better understand these interactions.

“Mapping the rock engravings represents a major step towards an enhanced understanding of the role of the Orinoco River in mediating the formation of pre-Conquest social networks throughout northern South America.”

The research was originally published in the journal Antiquity.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments