Planets far beyond our galaxy discovered for the first time by astrophysicists

Microlensing technique allows detection of distant worlds that could never be observed directly, 'not even with the best telescope one can imagine in a science fiction scenario'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Astrophysicists have discovered planets outside our galaxy for the first time ever.

Previously, planets have only been detected within the Milky Way.

However, by measuring an astronomical phenomenon called microlensing, scientists were able to identify a group of distant worlds using data from Nasa’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

The newly discovered planets ranged from the size of the moon to the size of Jupiter, and their galaxy is 3.8 billion light years away from our own.

"We are very excited about this discovery. This is the first time anyone has discovered planets outside our galaxy," said Professor Xinyu Dai, an astrophysicist at the University of Oklahoma.

The findings were published by Professor Dai and his colleague Dr Eduardo Guerras in The Astrophysical Journal.

Analysis of microlensing, which makes use of the brightness of distant celestial objects such as stars and quasars, is the only known method capable of identifying planets at such distances.

"This is an example of how powerful the techniques of analysis of extragalactic microlensing can be,” said Dr Guerras.

“This galaxy is located 3.8 billion light years away, and there is not the slightest chance of observing these planets directly, not even with the best telescope one can imagine in a science fiction scenario.

"However, we are able to study them, unveil their presence and even have an idea of their masses. This is very cool science."

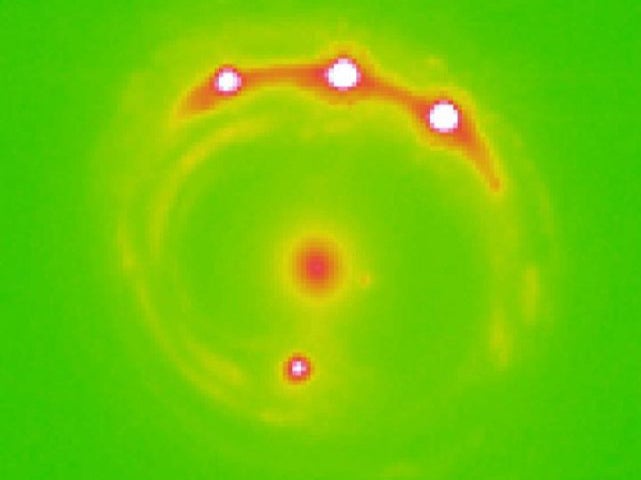

Microlensing is an astronomical effect in which light ray emanating from a distant star or quasar is bent by the gravity of an intermediary object – such as another star or black hole – when seen from Earth.

If the source is positioned precisely behind the intermediary, that object will act as a “lens” and create a disc of light as light rays from the source pass on all sides of it.

The brightness of these discs is affected by the presence of planets nearby the lensing star, and so this can be used to determine the presence of planets by stars that would otherwise be too far away to identify.

This effect was predicted by Einstein's general theory of relativity, and the discs of light that form are known as “Einstein discs”.

In Professor Dai and Dr Guerras’s work, they used a telescope to study the microlensing properties of emission of a background quasar, to make measurements they identified as evidence for planets.

"These small planets are the best candidate for the signature we observed in this study using the microlensing technique,” said Professor Dai.

“We analysed the high frequency of the signature by modelling the data to determine the mass."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments