3.5 billion-year-old fossil is oldest ever sign of life identified by scientists

Critics had previously argued microfossils were just unusual shapes in the rock

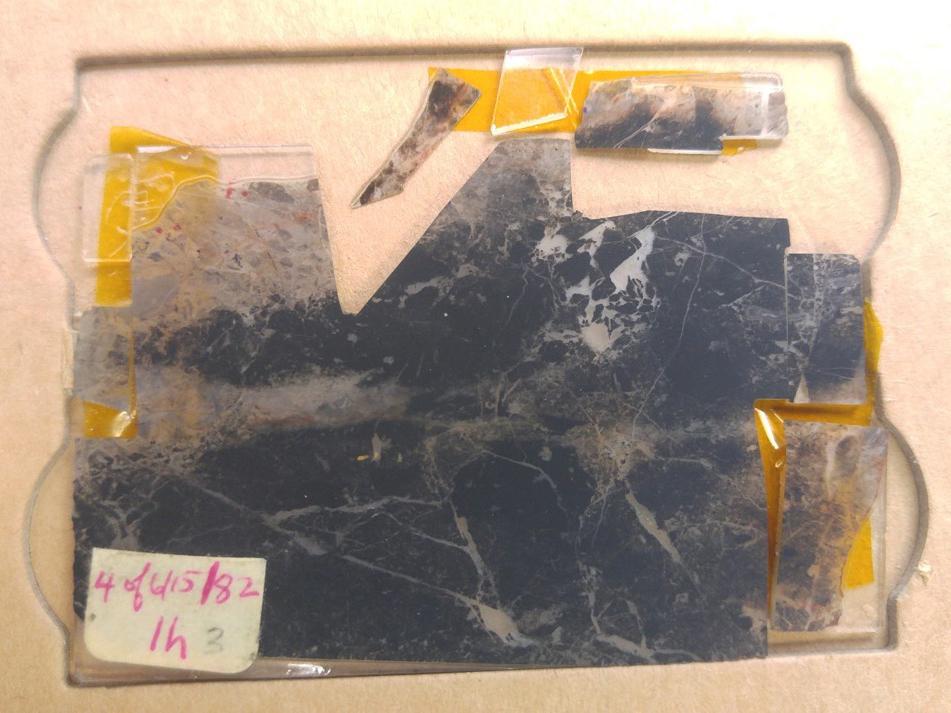

In a nearly 3.5 billion-year-old piece of rock from Western Australia, scientists have identified the oldest life forms ever known.

The evidence consists of cylindrical and thread-like shapes thought to be fossilised microbes from the early days of life on Earth.

The “microfossils” have been known for over two decades, but they have been the subject of considerable controversy within the scientific community.

Critics have suggested the fossils, which are invisible to the naked eye, are just unusual shapes in the rock and not evidence of life at all.

Now, work led by Professor William Schopf, the palaeobiologist who first described the specimens in 1993, has put the matter to rest.

“I think it’s settled,” said Professor Schopf, who is based at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Together with a team of collaborators, Professor Schopf analysed the carbon composition of the ancient rock to find out the ratios of different carbon isotopes – that is, different types of carbon.

They found the ratios corresponded with the microbe-like structures in the rock.

“The differences in carbon isotope ratios correlate with their shapes,” said Professor John Valley, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who co-led the study with Professor Schopf.

“If they’re not biological there is no reason for such a correlation.”

The technique for analysing these tiny fossils took the scientists 10 years to develop, and involves grinding down the original sample to carefully reveal the delicate fossils inside.

The study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, describes 11 different types of microbe from the rock, including some from lineages that are long-extinct and others similar to species still seen today.

The variety of microbes suggests a complex miniature ecosystem on ancient Earth, including species making energy from sunlight like modern plants, and others that produced or consumed methane.

The fact that such complexity existed 3.5 billion years ago suggests that the origins of life were actually much earlier, according to the scientists.

Other studies have shown that oceans existed on Earth 800 million years before the creatures in these fossils existed, and this could have facilitated earlier life.

“We have no direct evidence that life existed 4.3 billion years ago but there is no reason why it couldn’t have,” said Professor Valley.

“This is something we all would like to find out.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments