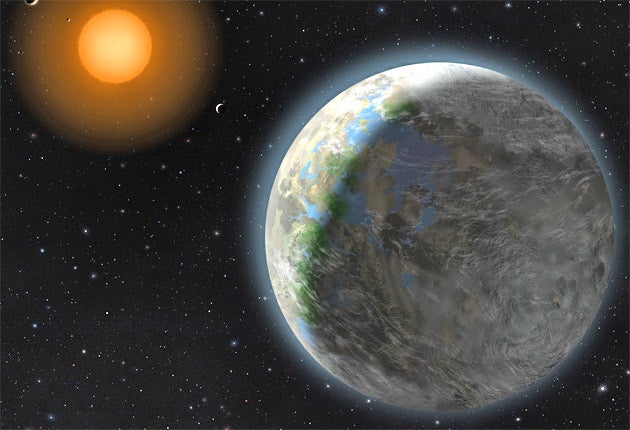

Not too hot, not too cold: could the 'Goldilocks' planet support life?

Astronomers excited by world 120,000 billion miles away in the Libra constellation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The search for a faraway planet that could support life has found the most promising candidate to date, in the form of a distant world some 120,000 billion miles away from Earth.

Scientists believe that the planet is made of rock, like the Earth, and sits in the "Goldilocks zone" of its sun, where it is neither too hot nor too cold for water to exist in liquid form – widely believed to be an essential precondition for life to evolve.

It is unlikely that anyone would be able to visit planet Gliese 581g in the near future as it would take 20 years travelling at the speed of light to reach it, and many thousands of years in a spacecraft built using the best-available rocket technology.

The planet is named after its star, Gliese 581, a red dwarf found in the constellation Libra, and is the sixth planet in its solar system. Scientists said last night that it is the most habitable planet yet found beyond our own Solar System, and a prime spot for the possible existence of extraterrestrial life.

Two previous claims for the existence of earth-like planets in the same solar system were subsequently found to be overstated in that they were either too far away or too near to Gliese 581, making it too cold or too hot for liquid water and life to exist.

However, the latest discovery, made by American astronomers, put the orbit of planet Gliese 581g between the orbits of the two previous contenders for earth-like worlds, said Professor Steve Vogt of the University of California at Santa Cruz, who led the study.

"We had planets on both sides of the habitable zone – one too hot and one too cold – and now we have one in the middle that's just right. This planet sits right between the two of them. It is right smack in the middle and it couldn't be more in the habitable zone where liquid water and life could exist," Professor Vogt said. "We estimate it has a mass of between three and four times that of Earth, which means it is small enough to be made of rock. It means it has a surface you could stand on and a gravity similar to Earth's that could hold a nice atmosphere in place," he added.

Calculations based on the planet's gravitational influence on its star suggest Gliese 581g is locked in a tidal embrace with its sun, meaning one hemisphere is constantly facing the star while the other is in total darkness facing space.

This implies a "terminator" line running round the planet, where the harsh light of day diminishes into the perpetual darkness of night. This would be the most hospitable place for life to exist because there would be a constant gradient of temperatures from very hot to very cold, Professor Vogt said.

"It could be quite a hospitable place provided the atmosphere is not made of solid ammonia or anything like that. We don't know what the atmosphere is made of because we don't take direct measurements of the planet, only its gravitational influence," he said.

The scientists calculate that the planet orbits its sun every 36 days and has a radius of between 1.2 and 1.5 times that of the Earth's, with a gravity strong enough to hold an atmosphere that can protect against ultraviolet light and the loss of gases into space. The discovery, published in Astrophysical Journal, is the result of 11 years of work at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii and was the result of newly-developed techniques for analysing data from old-fashioned ground telescopes, said Paul Butler of the Carnegie Institution in Washington.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments