New type of photosynthesis discovered that could change hunt for alien life

'It is amazing what is still out there in nature waiting to be discovered', says lead researcher

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The discovery of a new method that bacteria can use to harvest infrared light and turn it into energy has boosted scientific understanding of the limits of life on Earth and beyond.

Plants and some bacteria use a process called photosynthesis to create sugars from carbon dioxide and water, which they use as a power source.

Most life forms that use photosynthesis are driven by red light, but the new form discovered by an Imperial College London-led team is used by some organisms to power themselves using the infrared spectrum.

This “textbook-changing” revelation has the potential to expand scientists’ search for creatures on other planets, which often relies on the presence of life-promoting light.

“The new form of photosynthesis made us rethink what we thought was possible,” said Professor Bill Rutherford, a biochemist at Imperial College London.

“It also changes how we understand the key events at the heart of standard photosynthesis. This is textbook-changing stuff.”

The photosynthesis recognisable to many from current textbooks involves the green pigment chlorophyll-a, which gives plants their distinctive hue.

This pigment absorbs red light while reflecting away greens, blues and purples.

Chlorophyll-a is present in all plants, as well as algae and photosynthetic bacteria, and scientists long assumed that there was a “red limit” on photosynthesis.

Astrobiologists have used this supposed limit to gauge whether complex life could be evolving on distant planets in other solar systems.

However, some photosynthetic bacteria known as cyanobacteria have another trick up their microscopic sleeves.

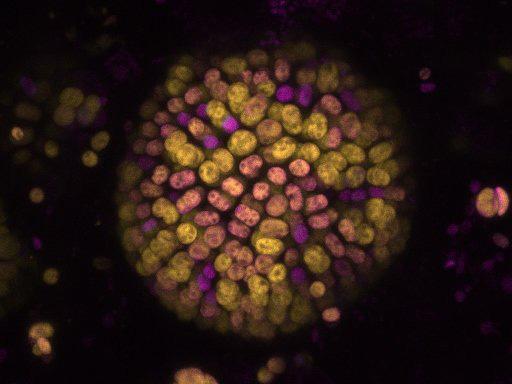

Researchers found another form of chlorophyll working in communities of these creatures growing in shaded conditions in “bacterial mats” in Yellowstone National Park and inside rocks found on Australian beaches.

In near-infrared light, the chlorophyll-a systems of these bacteria shut down and a different variety – chlorophyll-f – begins operating in lower energy conditions “beyond the red limit”.

Professor Rutherford and his team tested these abilities by placing cyanobacteria communities into cupboards fitted with infrared LEDs.

“Finding a type of photosynthesis that works beyond the red limit changes our understanding of the energy requirements of photosynthesis,” said Dr Andrea Fantuzzi, co-author of the study that was published in the journal Science.

“This provides insights into light energy use and into mechanisms that protect the systems against damage by light.”

Besides broadening the search for aliens, the discovery could help scientists genetically engineer crops that can survive in a wider range of light conditions.

Dr Dennis Nurnberg, the first author of the study, said: “I did not expect that my interest in cyanobacteria and their diverse lifestyles would snowball into a major change in how we understand photosynthesis.

“It is amazing what is still out there in nature waiting to be discovered.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments