New infertility treatment could grow sperm from skin cells

Your support helps us to tell the story

As your White House correspondent, I ask the tough questions and seek the answers that matter.

Your support enables me to be in the room, pressing for transparency and accountability. Without your contributions, we wouldn't have the resources to challenge those in power.

Your donation makes it possible for us to keep doing this important work, keeping you informed every step of the way to the November election

Andrew Feinberg

White House Correspondent

Infertile men who do not produce enough sperm to have children of their own could in the future be offered a new form of treatment based on converting their skin cells into the sperm-making tissue that is missing in their testicles, scientists said.

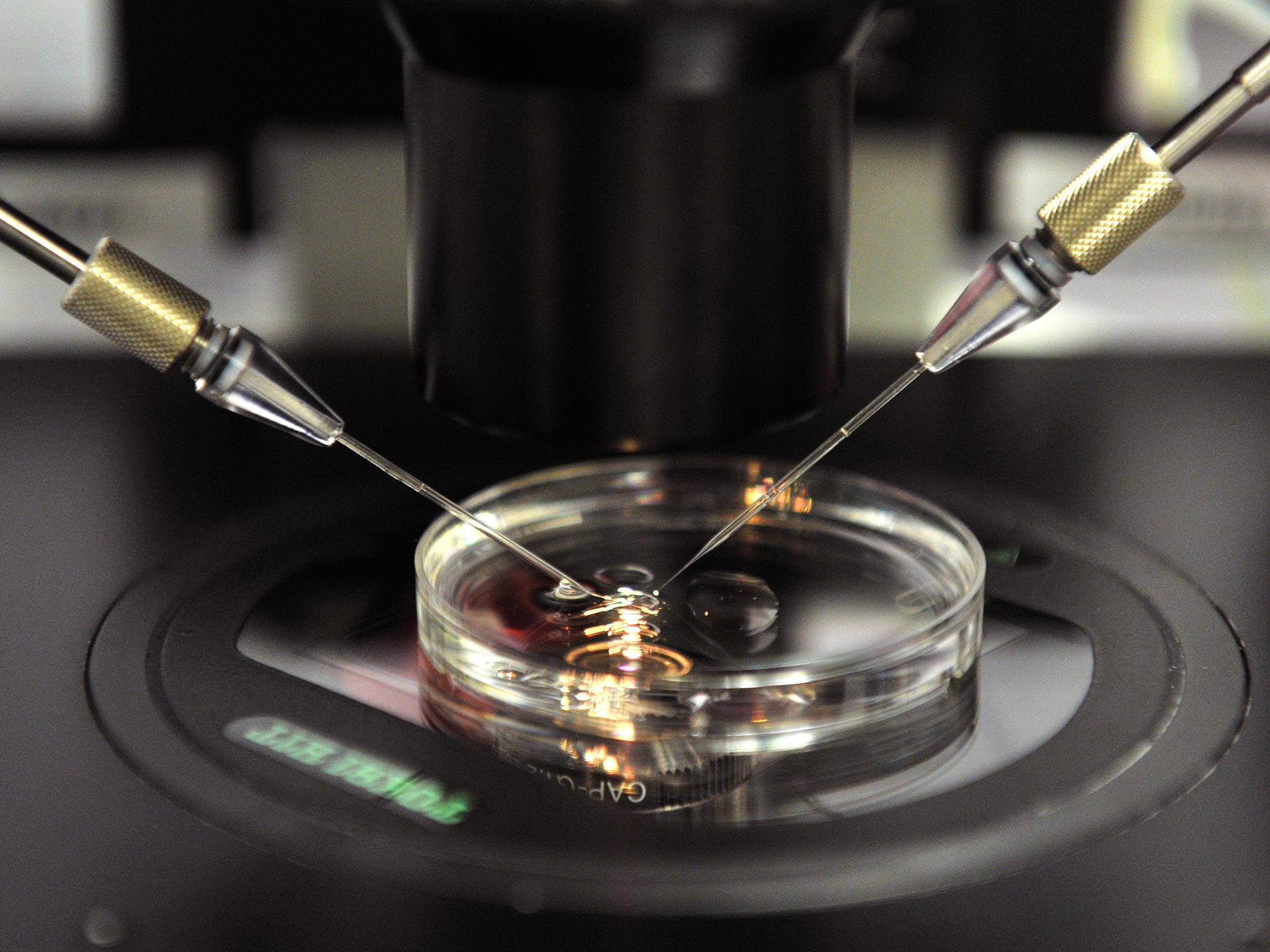

A study has found that it is possible to convert skin cells into the male “germ cells”, which are responsible for sperm production in the testes, using an established technique for creating embryonic stem cells using a form of genetic engineering.

The researchers showed that stem cells derived from human skin become active germ cells when transplanted into the testes of mice even when the man suffers from a genetic condition where he lacks functioning germ cells in his own testes.

Creating sperm-producing human cells in laboratory mice will allow scientists to study in more detail the complex sequence of events during the development if the male reproductive tissue, and to understand how these developmental changes can go awry in infertile men.

“Our results are the first to offer an experimental model to study sperm development. Therefore, there is potential for applications [such as] cell-based therapies in the clinic, for example, for the generation of higher quality and numbers of sperm in a dish,” said Renee Reijo Pera of Montana State University.

“It might even be possible to transplant stem cell-derived germ cells directly into the testes of men with problems producing sperm,” said Professor Reijo Pera, who led the study published in the journal Cell Reports. However, she emphasised that further research will be needed before clinical trials can be allowed on humans.

Although the mice had functioning human male germ cells, they did not produce human sperm, Dr Reijo Pera said. “There is an evolutionary block that means that when germ cells from one species are transferred to another, there is not full spermatogenesis, unless the species are very closely related,” she explained.

About one in a hundred men suffer from azoospermia, where they fail to produce measurable quantities of sperm in the semen. The condition is responsible for about 20 per cent of cases of male infertility, which itself accounts for about half of the 10-15 per cent of couples who have difficulty conceiving naturally.

The study involved creating “induced pluripotent” stem cells by adding key genes to the skin cells of five men – three with a form of azoospermia caused by a genetic mutation on the Y chromosome and two with normal fertility. The resulting stem cells were implanted into the testes of laboratory mice where they developed normally into germ cells.

The scientists found that even the stem cells derived from the infertile men were capable to developing into human male germ cells in the mouse testes. However, the stem cells of the men with the Y chromosome mutation produced about 100 times less germ cells than the men with normal fertility, Professor Reijo Pera said.

“Studying why this is the case will help us to understand where the problems are for these men and hopefully find ways to overcome them,” Professor Reijo Pera said.

“Our studies suggest that the use of stem cells can serve as a starting material for diagnosing germ-cell defects and potentially generating germ cells.

“This approach has great potential for treatment of individuals who have genetic or idiopathic [unknown] causes for sperm-cell loss, or for cancer survivors who have lost sperm production due to [anti-cancer] treatments,” she said.

Michael Eisenberg, director of male reproductive medicine and surgery at Stanford University in California, said: “This research provides and exciting and important step for the promise of stem cell therapy in the treatment of azoospermia, the most severe form of male factor infertility.

"In addition, it provides very intriguing possibilities for men rendered sterile after cancer treatments. Being able to efficiently convert skin cells into sperm would allow this group to become biological fathers.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments