Discovery of cave paintings and decorated shells reveals Neanderthals were artists

Artwork found in Spanish caves suggests ability to think symbolically and creatively was not unique to modern humans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Neanderthals had the ability to create works of art, according to a team of archaeologists.

The discovery of paintings made over 64,000 years ago in Spanish caves suggests Neanderthals possessed creativity and the ability to think symbolically, like modern humans.

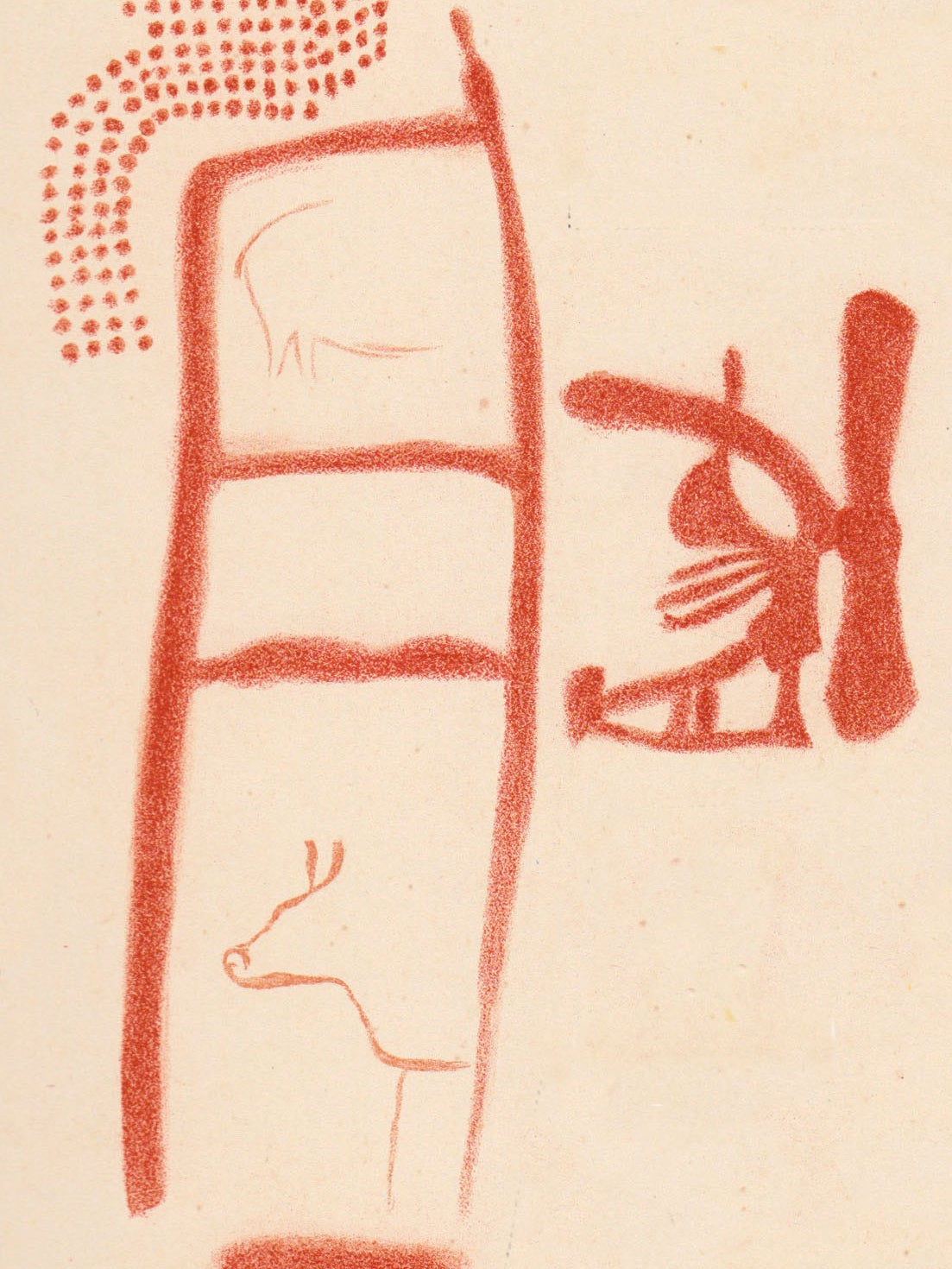

Among the works on display in these caves were paintings of animals, dots and geometric patterns, as well as hand stencils, hand prints and engravings.

Scientists who made the discovery said their findings contradict the historic notion of these ancient humans as “brutish and uncultured”.

“This is an incredibly exciting discovery which suggests Neanderthals were much more sophisticated than is popularly believed,” said Dr Chris Standish, an archaeologist at the University of Southampton who co-led the research.

“Our results show that the paintings we dated are, by far, the oldest known cave art in the world, and were created at least 20,000 years before modern humans arrived in Europe from Africa – therefore they must have been painted by Neanderthals.”

The work was carried out by a team of scientists from several European institutions, and their results were published in the journal Science.

A further study, published in Science Advances by the same team, documented the discovery of perforated and coloured marine shells in another Spanish cave.

These items were also thought to be Neanderthal in origin due to their age surpassing that of modern humans in the region.

Past claims that Neanderthals created art works – such as the geometric scratches found in the walls of a Gibraltar cave in 2014 – have been undermined by imprecise dating techniques. Radiocarbon dating, for example, has the potential to give incorrect age estimates.

As such, prior to these discoveries cave art has only been conclusively attributed to modern humans – Homo sapiens.

However, the scientists working on the newly discovered paintings used state-of-the-art uranium-thorium dating to provide more accurate age estimates.

They analysed calcium carbonate crusts that had developed over the cave paintings, allowing them to date the art without damaging it.

Taken together, the cave paintings and shells indicate the ability to think symbolically and creatively was not unique to modern humans.

In fact, it is likely that such an ability was present in the ancestors we share with Neanderthals, pushing it even further back in evolutionary history.

“On our search for the origins of language and advanced human cognition we must therefore look much farther back in time, more than half a million years ago, to the common ancestor of Neanderthals and modern humans,” said Professor Joao Zilhao, an archaeologist at the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies who contributed to the research.

As artworks were found in caves 700 kilometres apart, and spanning a period of 25,000 years, the practice appears to have been a widespread cultural tradition among Neanderthals.

The researchers suggested cave art found in other western European caves could also have been produced by Neanderthals.

They emphasised the role finds of this nature have on our perspective of humanity.

“The emergence of symbolic material culture represents a fundamental threshold in the evolution of humankind. It is one of the main pillars of what makes us human,” said Dr Dirk Hoffmann, an archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology who co-led the research.

“Artefacts whose functional value lies not so much in their practical but rather in their symbolic use are proxies for fundamental aspects of human cognition as we know it.”

“Soon after the discovery of the first of their fossils in the 19th century, Neanderthals were portrayed as brutish and uncultured, incapable of art and symbolic behaviour, and some of these views persist today,” said Professor Alistair Pike, an archaeologist at the University of Southampton and co-author of the study.

“The issue of just how human-like Neanderthals behaved is a hotly debated issue. Our findings will make a significant contribution to that debate.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments