Natural cooling of the Sun will not be enough to save Earth from global warming, warn scientists

The Sun is gradually becoming less and less active

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

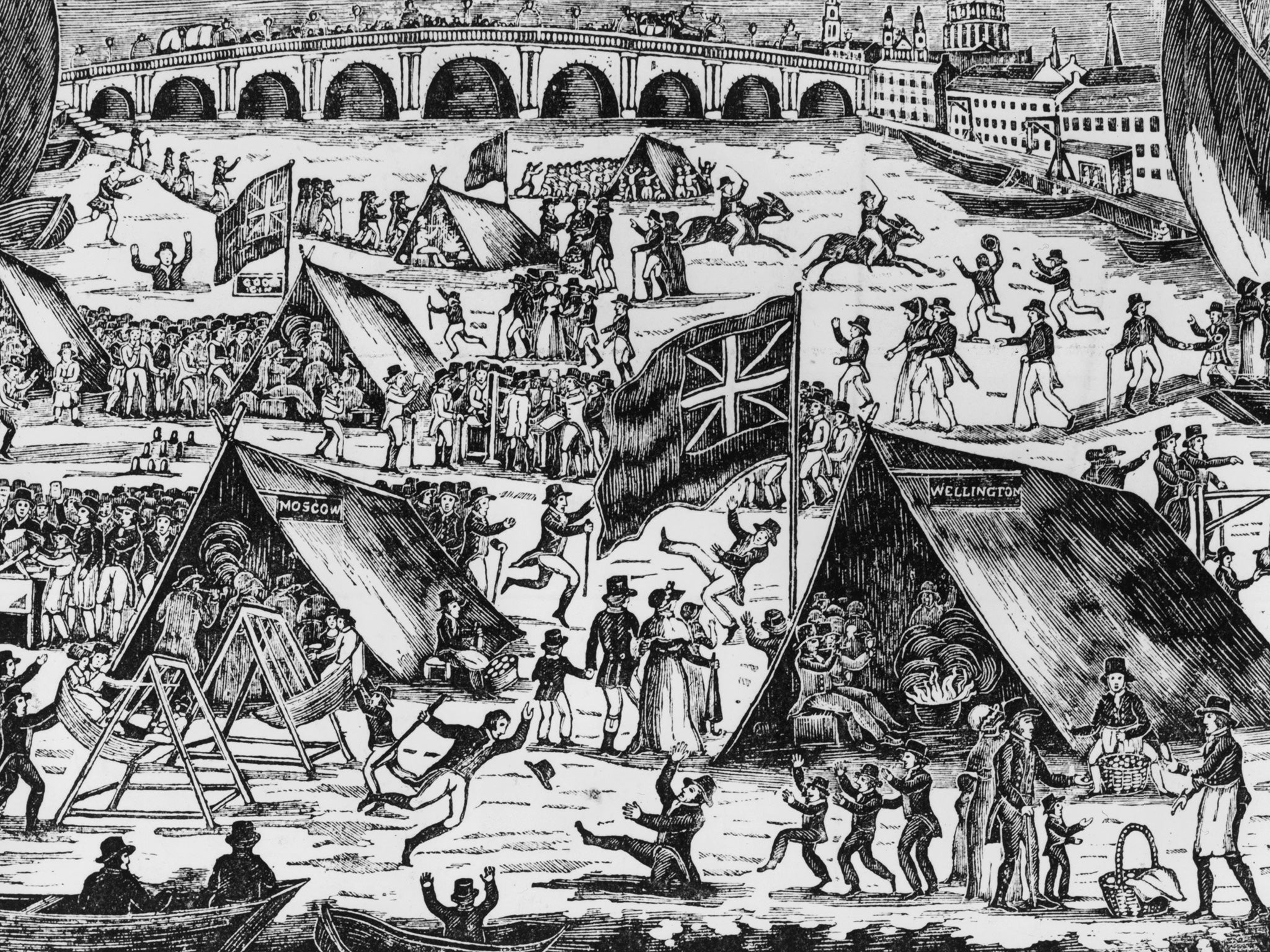

Your support makes all the difference.There is about a one-in-five chance of the Sun entering the same kind of cooling phase that allowed “frost fairs” to be held on the frozen River Thames 300 years ago – but scientists warned that the next solar transition will not be enough to save the world from global warming.

A rapid decline in the Sun’s activity is making it increasingly likely that within the next half century the world will experience a “grand solar minimum”, which is thought to have contributed to the so-called Little Ice Age in Europe and parts of North America in the 17th and 18th Centuries.

However, a study has found that the expected fall in global average temperature resulting from the natural, long-term fluctuations in solar activity will be dwarfed by the projected rise in temperatures due to man-made emissions of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide.

The last grand solar minimum – known as the Maunder minimum after 19th Century solar astronomers Annie and Walter Maunder – occurred between about 1645 and 1715 and was marked by the virtual disappearance of the 11-year cycle of sunspots, accompanied by a small but significant decline in the total solar radiation reaching the Earth.

Over the past several decades, the Sun has been in a “grand solar maximum” but it is quickly becoming less and less active, with an increasing probability of it entering a grand solar minimum by the end of the century, according to calculations based on radioactive isotopes affected by solar radiation over the past 9,300 years.

“The trajectory at the moment is on a path towards a Maunder minimum in the next 50 years but with an overall probability of about 20 per cent. However, over the next 100 years the probability rises to about 50 per cent,” said Professor Mike Lockwood, a solar physicist at Reading University.

“There is a significant probability that within the next half century we’d be entering another grand solar minimum and although that doesn’t make much difference to global average temperatures it might cause us in Europe to suffer more extreme cold winters,” Professor Lockwood said.

A study carried out on computer models at the Met Office Hadley Centre in Exeter calculated that a forthcoming grand solar minimum would cause global average temperatures to fall by about 0.1C. This compares to an expected increase of several degrees due to global warming if industrial emissions of greenhouse gases continue to rise at the present rate.

However, the regional impacts of a grand solar minimum on northern Europe and North America could be significantly greater, with temperatures falling on average by between about minus 0.4C and minus 0.8C, said Sarah Ineson, a Met Office researcher and lead author of the study published in the journal Nature Communications.

“This study shows that the Sun isn’t going to save use from global warming, but it could have impacts at a regional level that should be factored in to decisions about adapting to climate change for the decades to come,” Dr Ineson said.

“The regional impacts of a grand solar minimum are likely to be larger than the global effect, but it’s still nowhere near big enough to override the expected global warming trend due to man-made change,” she said.

“This means that even if we were to see a return to levels of solar activity not seen since the Maunder minimum, our winters would likely still be getting milder overall,” she added.

If winter temperatures fall by as much as they did in the 17th Century, changes to the flow of the River Thames and the extra heat caused by urban activity will mean that frost fairs on the frozen rivers are still unlikely to be possible even without global warming.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments