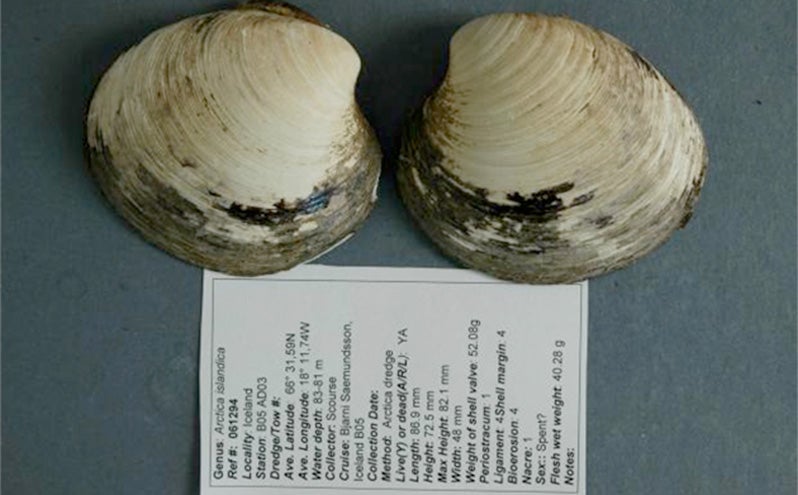

It's a clamity! Ming the clam, the world's oldest animal, killed at 507 years old by scientists trying to tell how old it was

Ming the clam was first discovered in 2006 and killed by scientists unaware of its age. Recent advances have revised Ming's age upwards by 103 years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A team of researchers from Bangor University have announced that the oldest animal in the world, a species of Icelandic clam known as an ocean quahog, was 507-years-old.

Known as Ming, the bivalve mollusc was ‘born’ in 1499, meaning it was swimming in the oceans before Henry VIII took the English throne. It was named after the Chinese Ming dynasty, which was in power when it was alive.

Ming was unfortunately killed by researchers when they opened its shell to find out how old it was. The unlucky mollusc was picked up from an Icelandic seabed back in 2006, but scientists were unaware of the creature's record breaking age.

It was originally thought to be 405 years old, but advantages in aging methodology means that this age has recently been revised upwards to 507 years.

“We got it wrong the first time and maybe we were a bit hastingly publishing our findings back then. But we are absolutely certain that we've got the right age now," Paul Butler, an ocean scientists from Bangor University, told ScienceNordic.

Like counting the rings of a tree, the age of bivalves is calculated by totting up growth rings - the lines left annually on the creatures’ shells by seasonal variations affecting how quickly they grow.

Ming’s original age had been calculated by counting the growth rings on the hinge of the clam, but as the creature was so incredibly old the rings had crowded together making them difficult to distinguish, with more than 500 packed into a space just millimetres across.

The new age of 507 years was calculated by instead counting the rings on the shell’s exterior, where they were more evenly spaced. By comparing unique growth patterns that have been previously linked with specific time periods they were able to verify Ming’s mighty age.

"It’s worth keeping in mind that we caught a total of 200 ocean quahogs on our Iceland expedition,” Butler told Science Nordic. “Thousands of ocean quahogs are caught commercially every year, so it is entirely likely that some fishermen may have caught quahogs that are as old as or even older than the one we caught.”

Scientists say that Ming’s long life is due to its incredibly slow metabolism, but also note that depending on how you define 'age' it is possible that the venerable bivalve is far from being the world’s oldest organism.

One species of jellyfish, for example, turritopsis dohrnii, is biologically immortal: instead of dying it simply reverts to an earlier stage in its life cycle. This means that there is no theoretical limit to its life span but also that it is impossible to verify its age.

The longest living terrestrial creature was Adwaita, a male giant tortoise that was estimated to be 255 years old when it died in 2006.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments