The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Methane gas find raises hopes of life beyond Earth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have for the first time detected methane gas in the atmosphere of a planet orbiting a distant star – an achievement that might soon lead to the discovery of extraterrestrial life.

Methane is an organic molecule which can be produced by biological activity but the scientists believe that its presence on this particular planet cannot be a by-product of living organisms as temperatures there are 900C – hot enough to melt silver.

However, the researchers said that just being able to detect methane on a planet beyond our own solar system shows that it is possible to find the vital signs of extraterrestrial life forms on other "extrasolar" planets more suitable to life.

"Methane is an organic molecule and so even if it is not produced by biological forces in the environment of this planet, finding methane in another planetary environment could indicate that life might be there," said Giovanna Tinetti, of University College London, who took part in the study published in the journal Nature.

Hubblecast 12- the murky planet

Video courtesy of ESA/Hubble Click here to see more Hubblecasts

"We haven't found life on another planet yet, but this is an exciting step towards showing that we can detect these signature molecules where they are present in the universe."

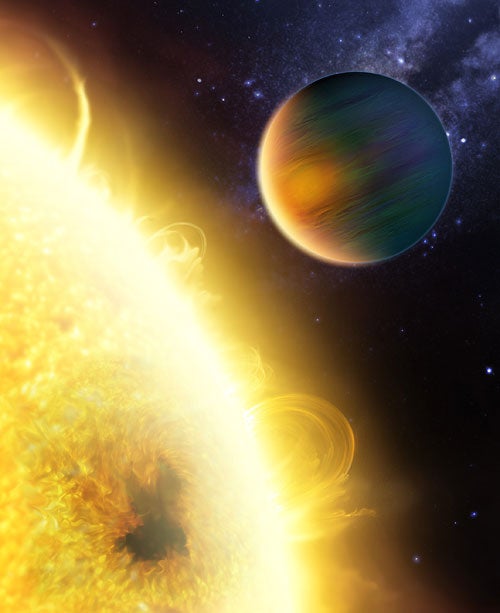

The extrasolar planet, known as HD 189733b, is composed of hot gases and is similar in size to Jupiter. It orbits close to its star – with each orbit lasting just two Earth days – and is "locked" so that one side faces its sun and is bathed in constant radiation, whereas the other is in constant darkness.

"The planet's atmosphere is far too hot for even the hardiest of life to survive – at least the kind of life we know from Earth. It's highly unlikely that cows could survive there," said Dr Tinetti.

An Anglo-American team of researchers used the Hubble Space Telescope to analyse the planet as it passed in front of its star by taking spectroscopic measurements of its atmosphere to determine its constituent molecules – which revealed methane.

As methane is eventually destroyed by photochemical reactions it is likely that the scientists were detecting the gas on the dark side of the planet.

"A sensible explanation is that the Hubble observations were more sensitive to the dark side of this planet where the atmosphere is slightly colder and the photochemical mechanisms responsible for methane destruction are less efficient than on the day side," said Dr Tinetti.

Click here to see the location of the planet on Google Sky

The planet is 93 light years from Earth in the constellation Vulpecula, "the little fox", and is one of about 270 "exoplanets" identified by astronomers since the first was discovered in 1995.

Most of these planets, however, are believed to be too large, gaseous and hot to support life as we know it but at least one, which is known as Gliese 581c, is sufficiently rocky, Earth-like and potentially habitable to at least support the possibility of life.

Mark Swain, of Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said that detecting "prebiotic" molecules was the necessary first stage in being able to confirm the existence of living organisms on distant planets.

"This is a crucial stepping stone to eventually characterising prebiotic molecules on planets where life could exist. This observation is proof that spectroscopy can eventually be done on a cooler and potentially habitable Earth-sized planet orbiting a dimmer, red dwarf-type star," said Dr Swain.

"These measurements are an important step to our ultimate goal of determining the conditions, such as temperature, pressure, winds, clouds and the chemistry of planets where life could exist. Infrared spectroscopy is really the key to these studies because it is best matched to detecting molecules."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments