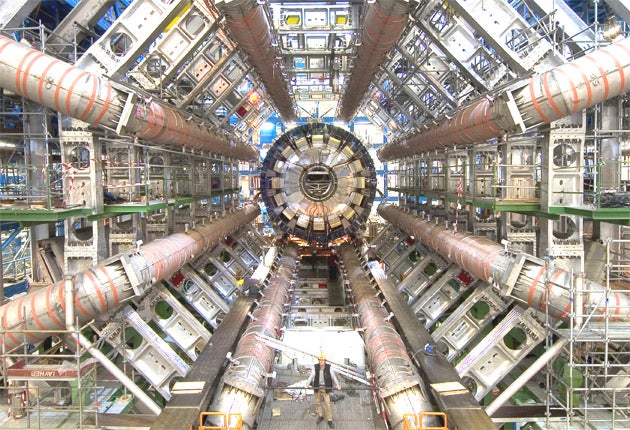

Large Hadron Collider is up and running again

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists switched on the world's largest atom smasher for the first time since the £6bn machine suffered a spectacular failure more than a year ago.

It took a year of repairs before beams of protons circulated late yesterday in the Large Hadron Collider for the first time since it was heavily damaged by a simple electrical fault. Circulation of the beams was a significant leap forward.

The European Organisation for Nuclear Research has taken the restart of the collider step by step to avoid further setbacks as it moves toward new scientific experiments - probably starting in January - regarding the makeup of matter and the universe.

Progress on restarting the machine, on the border between Switzerland and France, went faster than expected yesterday evening and the first beam circulated in a clockwise direction around the machine at about 10pm local time, said James Gillies, spokesman for the European Organisation for Nuclear Research.

"Some of the scientists had gone home and had to be called back in," Mr Gillies said.

The exact time of the start of the Large Hadron Collider was difficult to predict because it was based on how long it took to perform steps along the way, and in the end it happened about nine hours earlier than expected, Mr Gillies said.

This is an important milestone on the road toward scientific discoveries at the LHC, which are expected in 2010, he said.

About two hours later the scientists circulated another beam in the opposite direction, which was the initial goal in getting the machine going again and moving it toward collisions of protons, Cern said.

The LHC also will be used later for colliding lead ions - basically the nucleus of the element that is about 160 times as heavy as a single proton. That should reveal still more scientific secrets.

"It's great to see beam circulating in the LHC again," said Cern Director General Rolf Heuer.

"We've still got some way to go before physics can begin, but with this milestone we're well on the way."

With great fanfare, Cern circulated its first beams September 10, 2008.

But the machine was sidetracked nine days later when a badly soldered electrical splice overheated and set off a chain of damage to massive superconducting magnets and other parts of the collider, in a 17-mile circular tunnel under the Swiss-French border.

Cern has 40 million US dollars on repairs and improvements on the machine to avoid a repetition.

"The LHC is a far better understood machine than it was a year ago," said Steve Myers, Cern's director for accelerators.

"We've learned from our experience and engineered the technology that allows us to move on. That's how progress is made."

The LHC is expected soon to be running with more energy the world's current most powerful accelerator, the Tevatron at Fermilab near Chicago. It is supposed to keep ramping up to seven times the energy of Fermilab in coming years.

This will allow the collisions between protons on the machine to give insights into dark matter and what gives mass to other particles, and to show what matter was in the microseconds of rapid cooling after the Big Bang that many scientists theorise marked the creation of the universe billions of years ago.

The two parallel tubes the size of fire hoses send billions of protons whizzing around the collider in opposite directions at nearly the speed of light.

In rooms the size of cathedrals 300 feet below the ground the magnets force them into huge detectors to record what happens.

The beams travelled last night at a relatively low energy level, but Mr Gillies said the LHC was expected soon to start accelerating them soon so that the collisions they make will be more powerful - and revealing - creating as yet unseen insights into nature.

The LHC operates at nearly absolute zero temperature, colder than outer space, which allows the superconducting magnets to guide the protons most efficiently.

Physicists have used smaller, room-temperature colliders for decades to study the atom.

They once thought protons and neutrons were the smallest components of the atom's nucleus, but the colliders showed that they are made of quarks and gluons and that there are other forces and particles.

And scientists still have other questions about antimatter, dark matter and supersymmetry they want to answer with Cern's new collider.

The Superconducting Super Collider being built in Texas would have been bigger than the LHC, but in 1993 the US Congress cancelled it after costs soared and questions were raised about its scientific value

"The next important milestone will be low-energy collisions, expected in about a week from now," said Mr Gillies.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments