The reason why this 'difficult' puzzle is so easy to read

The scientific-sounding puzzle has been circulated online for years, but there's an element of truth to it

That famous 'jumbled letters' mind puzzle isn't all it seems.

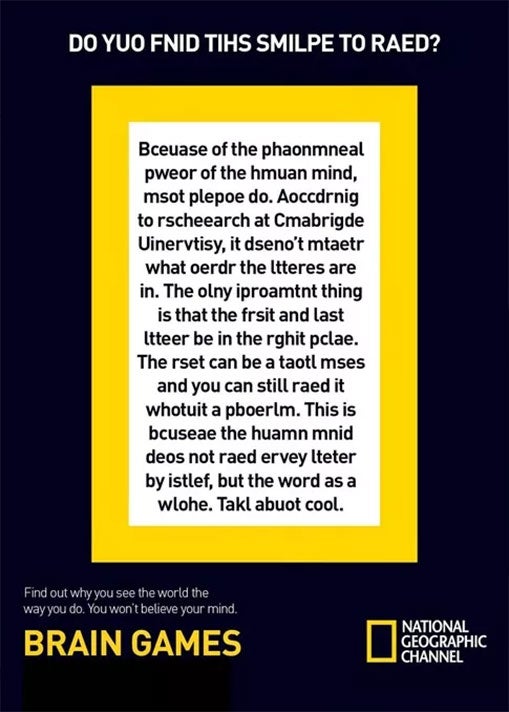

The well-known passage of garbled text, apparently developed at Cambridge University, appeared recently on question-and-answer site Quora, in response to the question: "What are some thing that neuroscientists know but most people don't?"

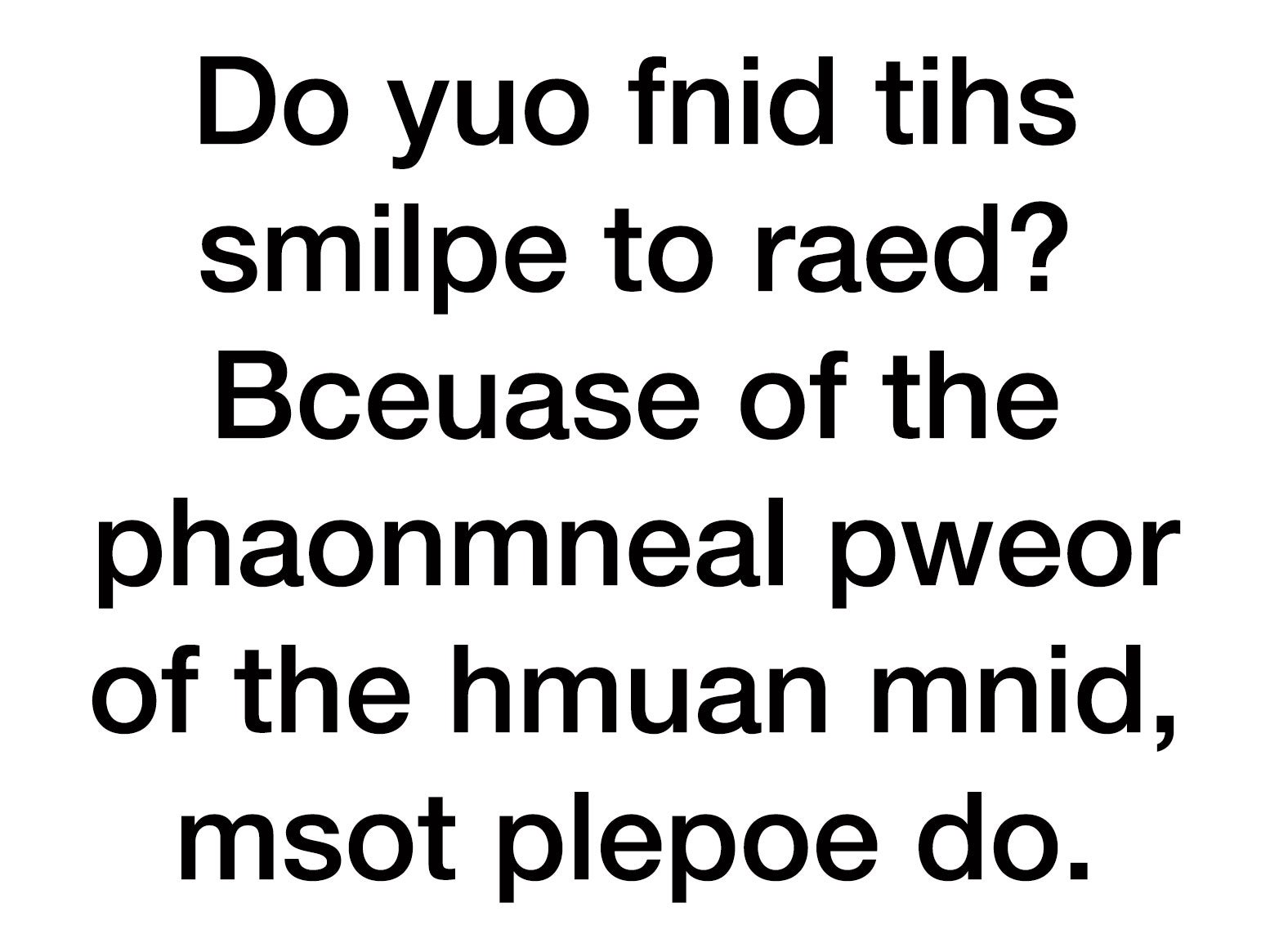

Naturally, as it does whenever neuroscience is mentioned on the internet, this picture made an appearance.

This passage, in various forms, has been floating around the internet for around 15 years. It's technically correct, but there's a couple of problems with it.

Firstly, according to Cambridge cognitive neuroscientist Matt Davis, there's no evidence that scrambled words have been the subject of research at Cambridge University.

The passage appears to have made its first appearance in the letters section of New Scientist magazine in 1999, when Graham Rawlinson wrote a letter about a study concerning the effects of reversing short chunks of speech, which was mentioned in a previous issue.

Rawlinson wrote: "This reminds me of my PhD at Nottingham University (1976), which showed that randomising letters in the middle of words had little or no effect on the ability of skilled readers to understand the text. Indeed one rapid readers noticed only four or five errors in an A4 page of muddled text."

Although it may be incorrect in its purported origins, it still has some scientific grounding.

As Matt Davis notes in his analysis of the text, it's essentially correct when it says "the human mind does not read every letter by itself, but the word as a whole."

It's true that people do not read each letter in a sentence individually, but this paragraph isn't the best illustration of that effect.

For example, in the sentence: "This is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the word as a wlohe," 10 of the 19 words are completely unchanged. Short words which link the sentence together and give it structure, such as 'and', 'by', 'a' and 'is' do not change, because they're too short to be rearranged. This keeps the sentence understandable, even if some of the words are misspelled.

What's more, many of the letters in some versions of the text look like they may have been jumbled in a way that keeps the words easily understandable - for example, 'porbelm' for 'problem' is easier at first glance than 'pleobrm'.

If you compare it with a slightly longer, more wordy sentence - like 'Pmrie miiestnr olpeny rdueilcis Ldonon myoar oevr leniavg the EU and akctats his leahsedrip aitniboms' - the effect isn't quite as strong.

The correct version of that sentence was: 'Prime minister openly ridicules London mayor over leaving the EU and attacks his leadership ambitions'. Even though the first and last letters were in the same place, as the text says they should be, it's pretty difficult to decipher.

The text in the picture is correct - although there's still a great deal of debate about what information we use while reading, it's thought that we do rely heavily on a word's shape and layout to decode its meaning, rather than the precise order of the letters. That's why the passage is so easy to read, despite being nonsense.

However, reading is a complex cognitive process, and we rely on far more than the positions of a word's first and last letters when we do it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments