It started with a shrew... study maps the primate family tree

They range in size from the tiny Madame Berthe's mouse lemur, weighing little more than an ounce, to the 440lb mountain gorilla.

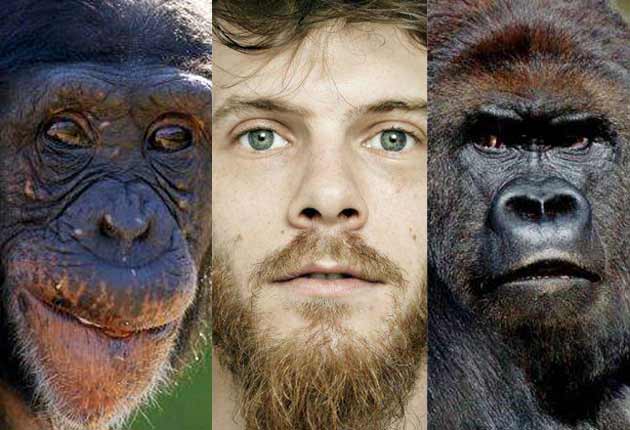

And the primate species, of course, incorporates humans, once famously described as the "third chimpanzee" because of the close genetic similarity with the two living species of chimp, the common chimp and the bonobo.

Even without the human component, the primates would include some of the most intelligent life forms on the planet and their extraordinary success is largely down to their relatively large brains, binocular vision and ability to grasp and manipulate objects between their four digits and opposable thumb.

Now for the first time scientists have drawn a comprehensive family tree of all living species of primates based on a systematic analysis of scores of key genes embedded within their DNA. It shows that Homo sapiens is just one of dozens of primate species that share a common ancestor, probably a small, shrew-like creature that lived during the age of the dinosaurs some 85 million years ago.

The complete phylogenetic tree of primates, published in the online journal PLoS Genetics, is based on a comparative analysis of some 54 separate gene regions within the genomes of 186 species of living primates covering the entire family tree, from the smallest lemur to the largest great ape. Scientists believe the study can, for the first time, accurately place Man within the much bigger and more complex tree of relationships that define primates. It should, they insist, provide invaluable insights into early human origins, as well as the diseases we share with our closest relatives.

"What is new from what we knew before is that we have a a high level of resolution for all branches within this tree. Simply put, a comprehensive primate phylogeny is resolved," said Jill Pecon-Slattery of the Laboratory of Genomic Diversity at the US National Cancer Institute in Maryland.

"It is a remarkably robust phylogeny, unusually so in the field of comparative genomics. Nearly every node and branch is unambiguously defined by genetic data, allowing a high level of confidence in reconstructing the primate evolutionary tree," Dr Pecon-Slattery said. Humans belong to the group of Old World primates, which are unusual for how slow they appear to be evolving compared to the fast-evolving New World monkeys of South America and certain branches of the lorises of south-east Asia.

"One of the most interesting findings is that humans are not evolving faster than other primate lineages, but in fact are among the slowest. This is not a new idea, as it is called the 'hominoid slow-down', but what is new is that it is not unique to humans," Dr Pecon-Slattery said.

"One of the more important applications of the new phylogeny is in human biomedicine. The resolution of the tree provides a foundation and guidepost for subsequent studies on the genetics of human health," she said.

"Only by comparing genomes across all of primates can we distinguish those traits that are uniquely human and what specific mutations are linked with disease, disease resistance, selection or adaptation.

"Now that we know how all primates are related, we can properly interpret the origin and function of mutations observed within genes targeted in human diseases," she added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks