Instagram's banning of pro-anorexia content may have made the problem worse, scientists find

Researchers found that Instagram's crackdown on pro-anorexia content may have actually made the problem worse

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A scientific study has found that Instagram's decision to ban certain words linked to pro-anorexia posts may have actually made the problem worse.

The study, conducted by a team at Georgia Tech, found that the censoring of terms like 'thighgap', 'thinspiration' and 'secretsociety', commonly used by anorexia sufferers, initially caused a decrease in use.

However, they found that users adapted by simply making up new, almost identical words to get around Instagram's moderation, often by altering spellings to create terms like 'thygap' and 'thynspooo'.

Instagram's censoring of pro-eating disorder (ED) content began in 2012, when they began limiting what users could see when searching for certain terms.

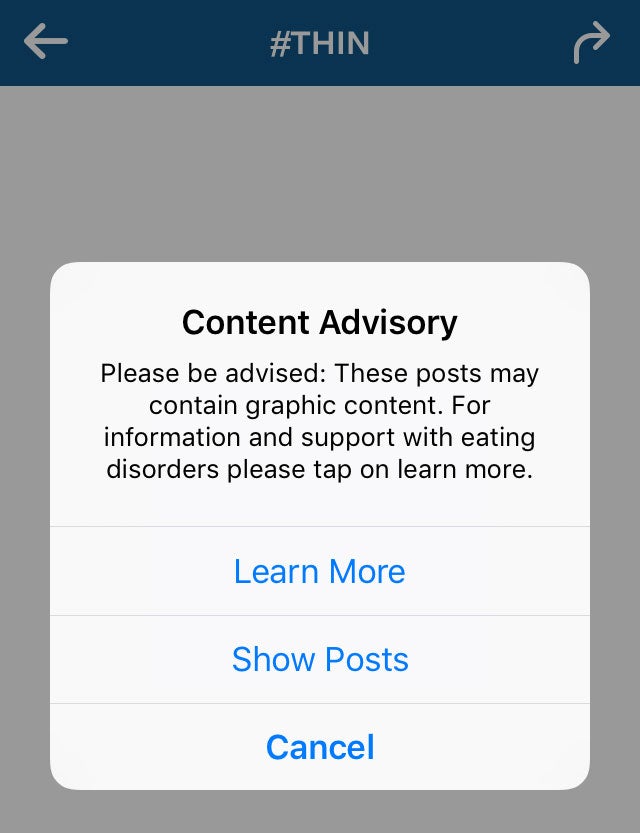

Some terms, like #thinspiration, simply return no results when searched for in the app. Other terms, like #thin, are still searchable, but users first have to read a message warning them about the content and directing them towards ED support services before they can see any pictures.

Researchers from the university's School of Interactive Computing combed through 2.5 million pro-ED posts from 2011 to 2014, to study how the community reacted to Instagram's moderation.

The 17 pro-ED terms which were intially moderated by Instagram were adapted into hundreds of new words. Each term had an average of 40 variables, and some had more - the researchers found 107 different spellings of 'thighgap' across the social network.

The team believe that by accidentally prompting the creation of these terms, Instagram polarised the vulnerable pro-ED community and actually increased how much members engaged with the content.

Munmun De Choudury, an assistant professor at the school, said: "Likes and coments on these new tags were 15 to 30 per cent higher than the originals."

"Before the ban, a person searching for hashtags would only find their intended word. Now a search produces dozens of similar, non-censored pro-ED terms. That means more content to view and engage with."

More worryingly, the team found that the content on these alternative terms tended to discuss self-harm, suicide and feelings of isolation more often than the wider internet community of eating disorder sufferers - however, speaking to Gizmodo, De Choudhury said they were not drawing any causal links with this observation.

Rather than ban words outright, the team suggested that Instagram take more direct action to provide sufferers with information about places that can help.

Stevie Chancellor, a doctoral student in Human Centred Computing who worked on the study, said: "Allow them to be searchable. But once they're selected, the landing page could include links for help organisations."

"Maybe the search algorithms could be tweaked. Instead of similar terms being displayed, Instagram could introduce recovery-related terms in the search box."

An Independent on Sunday report from 2014 revealed that the number of children and teenagers seeking help for an eating disorder had risen by 110 per cent in the previous three years, something which Childline partially blamed on the rise of social media.

The Georgia Tech team hope their research will help social networks deal better with vulnerable groups in the future.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments