Human brain could be 'hard-wired' towards altruism, scientists say

'The more we experience the states of others, the more we appear to be inclined to treat them as we would ourselves'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Altruism may be “hard wired” into the human brain, scientists have suggested.

How inherently good humans are – or aren’t – has been an issue which has occupied philosophers for centuries.

However, researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) have used science to try and find out.

They came to the conclusion that "our altruism may be more hard-wired than previously thought," according to Leonardo Christov-Moore, a postdoctoral fellow at UCLA's Semel Institute of Neuroscience and Human Behaviour.

The research also indicates a potential method of encouraging less selfish and more altruistic characteristics, said senior author Marco Iacoboni, a UCLA psychiatry professor.

"This is potentially ground-breaking," said Prof Iacoboni.

The claims follow the findings of two studies.

In the first study, researchers analysed brain activity in 20 participants.

This was done by scanning participants' brains while they were shown a video of a hand being poked with a pin and asked to imitate photographs of faces displaying a range of emotions.

In particular, the scientists looked at the cluster of parts of the brain known as the amygdala, somatosensory cortex and anterior insula. These are associated with experiencing pain and emotion and imitating other people.

They also looked at the dorsolateral and dorsomedial parts of the prefrontal cortex, which regulate behaviour and control impulses.

Participants then played the ‘dictator game’, a task often used by social scientists to study decision making.

They were given money - $10 per round for 24 rounds - to either keep for themselves or share with a stranger. Recipients were Los Angeles residents whose real ages and income levels were used in the experiment.

After each participant had completed the task, researchers compared their pay outs with their brain scans.

Participants with the most activity in the prefrontal cortex – associated with behaviour and impulse control - proved to be the least generous, giving away an average of only $1 to $3 per round.

But the one-third of the participants who had the strongest responses in the areas of the brain associated with perceiving pain and emotion and imitating others were the most generous.

On average, these subjects gave away approximately 75 per cent of their money.

Researchers referred to this tendency as "prosocial resonance" or mirroring impulse, and they believe the impulse is a primary driving force behind altruism.

"It's almost like these areas of the brain behave according to a neural Golden Rule," Mr Christov-Moore said.

"The more we tend to vicariously experience the states of others, the more we appear to be inclined to treat them as we would ourselves."

In the second study, researchers looked at if the behaviour and impulse controlling prefrontal cortex also restricts the altruistic mirroring impulse.

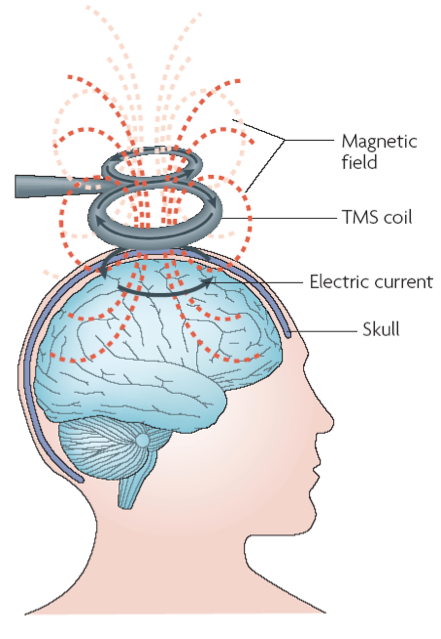

A non-invasive procedure called theta-burst Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation was used on 58 participants to numb brain activity in specific areas.

Participants with dumbed-down activity in the prefrontal cortex were found to be 50 per cent more generous than participants who were numbed elsewhere in the brain.

"Knocking out these areas appears to free your ability to feel for others," Christov-Moore said.

The findings of both studies suggest potential avenues for increasing empathy, which is especially critical in treating people who have experienced desensitizing situations like incarceration or war.

"The study is important proof of principle that with a noninvasive procedure you can make people behave in a more prosocial way," Prof Iacoboni said.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments