Hair-splitting, brazen denials and six decades of dirty tricks

'Anything can be considered harmful. Apple sauce is harmful if you get too much of it,' a Philip Morris memo claimed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ever since the link between smoking and lung cancer was established more than 50 years ago, the tobacco industry has displayed extraordinary tenacity when it comes to denying the scientific evidence showing that smoking kills.

In 1952, a young British scientist named Richard Doll, working with his mentor Professor Bradford Hill, compiled a seminal study published in the British Medical Journal that established a "real association between carcinoma of the lung and smoking". Over the next few years and decades, the evidence became stronger, but just as soon as this evidence began to emerge, Big Tobacco was quick to launch a damage-limitation exercise. It would be many decades before the industry would reluctantly accept the scientific evidence showing that smoking causes lung cancer.

As early as 1953, the tobacco industry sought to spread disinformation to counter the medical evidence. Tobacco companies hired New York public-relations company Hill & Knowlton to "get the industry out of this hole", as industry documents released four decades later, as part of legal processes, revealed. "We have one essential job – which can be simply said: Stop public panic... There is only one problem – confidence, and how to establish it; public assurance, and how to create it," one Hill & Knowlton document said.

"And, most important, how to free millions of Americans from the guilty fear that is going to arise deep in their biological depths – regardless of any pooh-poohing logic – every time they light a cigarette," it said.

In the UK, British American Tobacco (BAT) even invented a secret code word for lung cancer that was to be used in its internal memos. The "C" word was to be substituted with ZEPHYR. As one BAT memo written in 1957 stated: "As a result of several statistical surveys, the idea has arisen that there is a causal relationship between ZEPHYR and tobacco smoking, particularly cigarette smoking."

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, tobacco companies were brazen in their denials despite the mounting scientific evidence linking smoking with a range of cancers and serious respiratory illnesses. "None of the things which have been found in tobacco smoke are at concentrations which can be considered harmful," said a Philip Morris document written in 1976. "Anything can be considered harmful. Apple sauce is harmful if you get too much of it."

During the 1980s, memos meant for internal consumption only show that behind closed doors, there were doubts about whether the denialist charade could be maintained for much longer. "The company's position on causation is simply not believed by the overwhelming majority of independent observers, scientist and doctors," said one internal document within BAT.

And then in the 1990s came another bombshell from the scientists. Second-hand smoke inhaled by "passive smoking" was linked with ill health and there were calls to introduce smoking bans.

In 1992, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) produced a report on "environmental tobacco smoke" and concluded that it is a cancer-causing substance. In Britain, a 1998 report of the Scientific Committee on Tobacco and Health stated: "Passive smoking is a cause of lung cancer and childhood respiratory disease. There is also evidence that passive smoking is a cause of ischaemic heart disease and cot death, middle-ear disease and asthmatic attacks in children."

Despite the evidence, the tobacco companies refused to accept the conclusions. Philip Morris, the world's biggest cigarette company, launched a pro-active campaign to undermine the scientific case against second-hand smoke, highlighting what it labelled as "junk science". Its strategy was best summed up in a letter written in 1993 by Ellen Merlo, senior vice-president of corporate affairs, to her chief executive at Philip Morris. "It is our objective to prevent states and cities, as well as businesses, from passive-smoking bans," she wrote.

Today, many tobacco companies have accepted that smoking causes lung cancer, but they still refuse to state that passive smoking can cause disease in non-smokers. They merely point to the fact that many health bodies believe this to be the case.

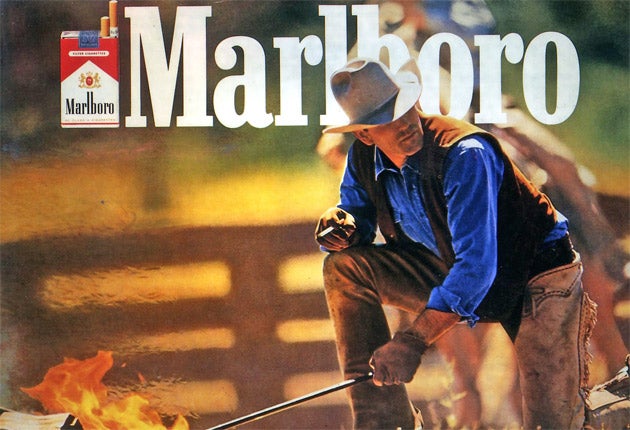

But having lost the debate over smoke-free offices and public spaces, the industry is now turning its sights on the next big fight, against the possible introduction of plain cigarette packaging that is devoid of all logos and branding.

Their fight against these proposals is again based on undermining the scientific evidence that plain packaging can reduce the number of children and young adults who take up smoking.

They seek to discredit both the research and the academics who carry out these studies. It is a tactic they have employed for more than half a century of scientific denialism.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments