Has Everest's Hillary Step really collapsed? Here's the science

Reports claim the last major obstacle before the summit has vanished, but then mountains are always changing shape

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Hillary Step, a rocky outcrop at 8,770m above sea level, just beneath the summit of Everest (8,850m), has finally succumbed to gravity and partially collapsed. At least it has according to mountaineer Tim Mosedale, who climbed the mountain this year. His claim has been refuted by the chair of the Nepal Mountaineering Association, however, sparking a debate which looks set to rage for some time yet. The definitive answer, after all, is located only a few metres short of the top of the world.

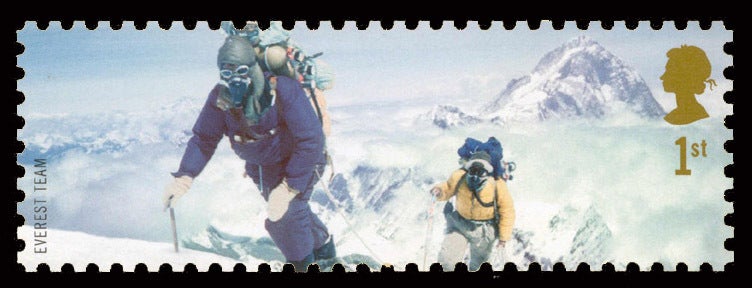

Named after Sir Edmund Hillary – the first to reach the summit of Everest, with Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, in May 1953 – this rocky structure certainly has a noble heritage in mountaineering circles. It is the last major obstacle encountered on the South Col route before reaching the summit.

But it also famed in geological circles. It is, or was, formed of a resistant limestone band along the base of the Qomolangma Formation which dates back to the Upper Cambrian or Lower Ordovician age. These rocks feature tiny remnants of crinoid ossicles (stems of sea lilies) that originally lived in a shallow tropical ocean 450 million years ago and can now be found on the summit of Everest.

If the Hillary Step has indeed collapsed, the rockfall will have altered the standard route to the top. And this may result in increasing congestion as parties queue up to get to the summit during the brief period of stable, pre-monsoon climbing conditions in May. As Mosedale told the Planet Mountain website: “It’s easier going up the snow slope and indeed for inexperienced climbers and mountaineers there’s less ‘climbing’ to be done, making it much easier for them. However, it’s going to form a bottleneck. The Hillary Step often formed a bottleneck but some years ago they fixed an up and a down rope. In the current state it would be difficult to safely negotiate down where the step used to be on account of the huge unstable rocks that are perched on the route.”

Ultimately, however, the demise of the Hillary Step would be but a small blip in the long-term process of Himalayan mountain building. The collision and ongoing convergence of the Indian plate into Asia results in convergence across the Himalayas of about 18-20mm per year and an average uplift rate of the mountains of about 3-4mm per year.

As the mountains are driven upwards by these tectonic forces, climatic and geographic forces – such as rain and snowfall, and glacial and river incision – conspire to bring them back down through erosion.

The tectonic forces have been winning this battle for at least 25 million years and the highest Himalayan peaks now reach nearly 9km above mean sea-level. The steeper the cliff faces, the more subject they are to rockfall and avalanches, and seasonal freeze-thaw cycles are important factors in making the rocks unstable. The collapse of the Hillary Step would be just one minor event in the broad scheme of uplift and erosion along the Himalayas.

Recent previous examples of large-scale rockfalls include the massive one on the west flank of Annapurna IV (7,525 metres) in spring 2012, which resulted in debris blocking the course of the upper Seti river in Nepal. A lake built up behind the blockage and a few days later, on 5 May, 2012, a massive mud-flow cascaded down the valley burying villages and killing 72 people. The flows reached as far as Pokhara, the second city of Nepal.

During the Gorkha earthquake (magnitude 7.9) in Nepal on 25 April, 2015, hundreds of rockfalls resulted from the intense ground shaking, sending boulders the size of houses tumbling down to the valleys and villages below. It has been hypothesised that this earthquake might have caused the collapse of the Hillary Step.

Perhaps the worst example was the massive rockfall that occurred on the south face of Langtang Lirung following the 12 May aftershock. The landslide originated from high on the south face of Langtang Lirung and the resulting rockfall completely buried the village of Langtang, killing at least 300 people.

In 1991, a large rockfall also occurred near the summit of Mount Cook in New Zealand, reducing its height from 3,764 metres to 3,724 metres. During June 2005, a series of major rockfalls caused most of the granite south-west pillar of the Aiguille de Dru in the French Alps (commonly known as the Bonatti Pillar) to collapse, wiping out one of the most famous Alpine rock climbs of all. The scar of this rockfall was more than 500 metres high and 80 metres wide.

But the story of mountains is a very, very long one – and it contains a great many twists and turns. The India-Asia plate collision has been going on for at least 50 million years. The tectonic forces push them up and erosion tries to wear them down.

Everest is continually being jacked up by this under-thrusting of the Indian plate and, as long as India continues to push north, indenting into Asia, the Himalayas will continue to rise.

As long as the Himalayas continue to rise, the forces of nature will erode them away and attempt to reduce these magnificent mountains back down to sea-level. And as long as that happens, they will keep changing shape. Long may tectonic forces prevail in this battle.

Mike Searle is a professor of earth sciences at the University of Oxford. This article was originally published on The Conversation (www.conversation.com)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments