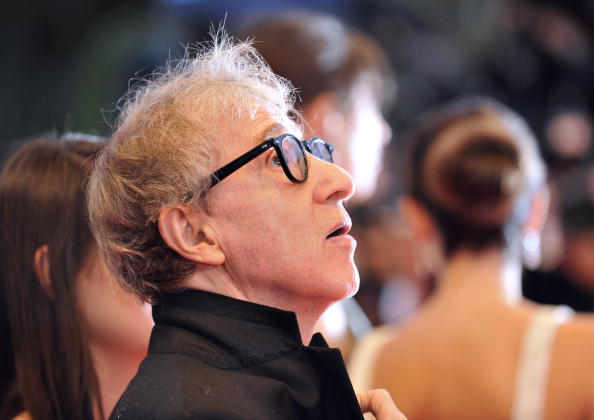

Don't worry, Woody: anxiety is in the genes, study finds

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some people are more prone to extreme anxiety because of a genetic mutation that they have inherited, according to one of the first studies to investigate the genetic basis of personality differences that can lead to stress disorders.

The mutation is found in about half the population but it exerts its effect on the one in four people who have inherited both copies of it from their parents, the study has found. Such people are at significantly higher risk of being more anxious than the general population and of suffering from anxiety-related conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive illnesses.

Scientists say the findings show that it is possible to identify genetic differences between people that directly affect the neuro-transmitting chemicals in the brain influencing variations in psychological traits.

Although many factors affect anxiety, the researchers believe the discovery opens the way to identifying further genes that can predispose someone to becoming nervous to the point of developing a psychological illness.

"This single gene variation is potentially only one of many factors influencing such a complex trait as anxiety. Still, to identify this first candidate for genes associated with an anxiety-prone personality is a step in the right direction," said Christian Montag of the University of Bonn, a member of the research team.

"It might be possible to prescribe the right dose of the right drug, relative to genetic make-up, to treat anxiety disorders," Dr Montag said.

The study focused on a gene known as COMT, which controls an enzyme that breaks down and so weakens the signal of dopamine, a key neurotransmitter in the brain associated with several psychological conditions, such as Parkinson's disease and schizophrenia.

The gene comes in two variations, met158 and val158, and the people who are most likely to be anxious are those who have inherited both copies of the met158 gene variant from each of their parents. In the white European population, about 25 per cent of people have this genetic make-up. The theory is that people with both copies of the met158 gene variant have a stronger dopamine signal in their brain, which results in an "inflexible attentional focus" – they cannot tear themselves away from an unpleasant stimulus even if it is a bad one.

The scientists, whose study is published today in the journal Behavioural Neuroscience, investigated the role of the COMT gene variations on 96 young women who fell into one of three genetic makeups – met/met, val/val or met/val.

Martin Reuter, a Bonn University researcher who was a leading member of the research team, said that the women were each shown images of varying unpleasantness while being subjected to a sudden loud noise to startle them so that their blink reflex could be measured.

"We used the startle reflex because it's a very old evolutionary indication of anxiety. It's not something you can manipulate or fake. The startle response is stronger when they were watching a negative image, and there was a significantly greater startle response from the met/met women compared with the rest of the group," Dr Reuter said. "Anxiety is a very complex phenomenon and many genes are responsible for it but this particular genetic variation, although involved in a small part of the anxiety response, is an essential part of it."

One of the longer-term goals of the study is to be able to identify the gene variations that predispose some people to extreme anxiety in order that drugs can be designed to combat the risk, Dr Reuter said. "It may give us a hint for drug therapy, but the brain is very complex," he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments