The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Dinosaur parasites found filled with blood and trapped in amber

Newly discovered fossilised ticks sucked the blood of prehistoric reptiles nearly 100 million years ago

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a scenario reminiscent of Jurassic Park, palaeontologists have found dinosaur parasites – one of which is filled with blood – trapped in amber.

The parasites have been identified as a new species of tick, named Deinocroton draculi or “Dracula’s terrible tick”.

These ticks would have sucked dinosaur blood almost 100 million years ago.

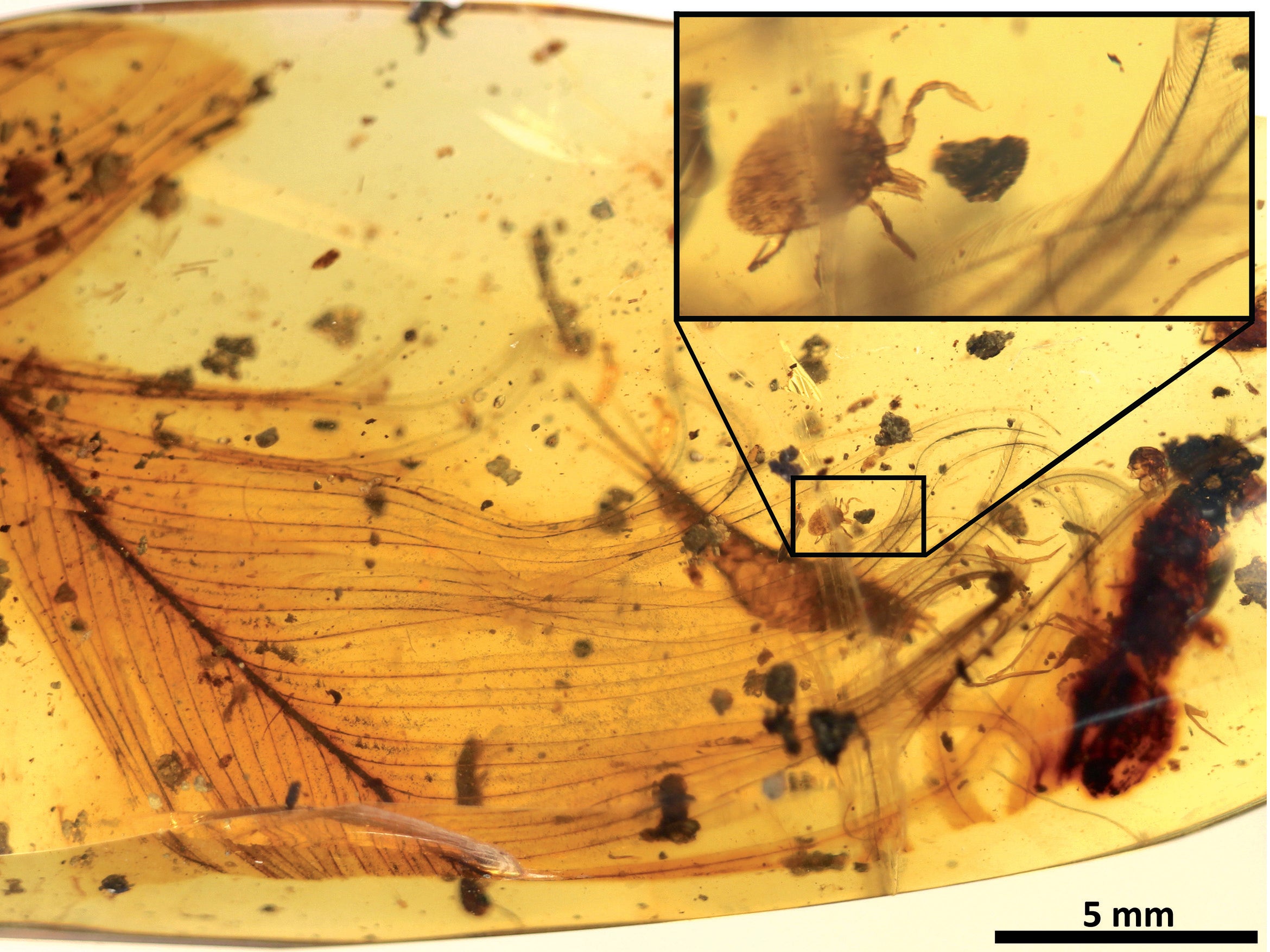

The scientists found one of the ticks encased in a piece of amber – tree resin that has hardened and fossilised – and grasping a feather.

It was the feather that indicated the preferred dinosaur targets for these prehistoric parasites.

“The fossil record tells us that feathers like the one we have studied were already present on a wide range of theropod dinosaurs,” said Dr Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente, a palaeobiologist at Oxford University Museum of Natural History and one of the authors of the study describing the parasites.

“Although we can’t be sure what kind of dinosaur the tick was feeding on, the mid-Cretaceous age of the Burmese amber confirms that the feather certainly did not belong to a modern bird,” he said.

Birds only appeared later in the age of the dinosaurs, when some feathered dinosaurs evolved into modern-day birds.

The fossils are the oldest known blood-sucking parasites identified, and represent the first direct evidence of ticks parasitising dinosaurs.

One of the ticks the palaeontologists found was swollen to eight times its normal size with blood.

While comparisons with the book and movie franchise are tempting, any Jurassic Park-style cloning of dinosaurs from blood found in amber won’t be possible with these specimens.

DNA does not preserve easily, so all attempts to extract it from amber millions of years after fossilisation so far have been unsuccessful.

The condition of these specimens also makes it difficult to analyse the blood and determine the creature to which it belonged.

“Assessing the composition of the blood meal inside the bloated tick is not feasible because, unfortunately, the tick did not become fully immersed in resin and so its contents were altered by mineral deposition,” said University of Barcelona researcher Dr Xavier Delclòs, one of the authors of the Nature Communications paper.

However, the scientists did find fragments of the larvae of some even smaller creatures, skin beetles, attached to the bodies of the ancient ticks.

The presence of these beetles, which are often found in birds’ nests today, provide further evidence that these creatures were feeding on feathered dinosaurs.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments