First-ever fossilised dinosaur brain discovered in Sussex after 133 million years

Remains of the creature hint that dinosaurs may have had bigger brains than previously thought

A brown pebble found in Sussex 10 years ago is actually the fossilised brain of a dinosaur thought to have lived 133 million years ago, scientists have revealed.

It is the first time anyone has seen what a dinosaur brain looked like as no other fossils have been found.

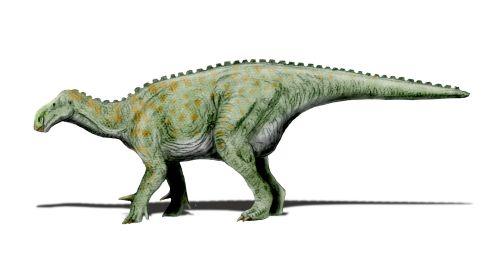

And the researchers said the discovery raised the tantalising prospect that the creature, believed to be a species similar to an Iguanodon, may have had an unexpectedly large brain.

However, they cautioned against drawing any conclusions about the dinosaur’s intelligence.

Normally, brain tissue would have quickly decayed, but it is thought the dying animal fell into a bog and the organ was pickled by the highly acidic and low-oxygen water.

One of the researchers, Dr Alex Liu, of Cambridge University's Department of Earth Sciences, said: “The chances of preserving brain tissue are incredibly small, so the discovery of this specimen is astonishing.”

The stone was found by fossil hunter Jamie Hiscocks, near Bexhill in Sussex in 2004, and he sent it to the late Professor Martin Brasier, of Oxford University.

Mr Hiscocks, named as a co-author of a special publication by the Geological Society of London about the fossil, said he “always believed I had something special”.

“I noticed there was something odd about the preservation, and soft tissue preservation did go through my mind,” he said.

“Martin realised its potential significance right at the beginning, but it wasn't until years later that its true significance came to be realised.

“In his initial email to me, Martin asked if I'd ever heard of dinosaur brain cells being preserved in the fossil record.

“I knew exactly what he was getting at. I was amazed to hear this coming from a world renowned expert like him.”

The researchers used a scanning electron microscope to identify membranes, called meninges, that surrounded the brain.

Structures that could be brain tissue itself also appear to be present.

The scientists said there were similarities between the fossil and the brains of birds and crocodiles, the descendant of the few dinosaurs that managed to survive the Earth’s last mass extinction of life about 65 million years ago.

However, reptiles’ brains are normally shaped like a sausage with about half of the skull cavity taken up by blood vessels and sinuses.

In this case the fossilised brain appears to press directly against the skull, which could mean the dinosaur had a bigger brain than previously thought.

But the researchers said it was more likely that the dinosaur’s head had been upside down, so as the brain decayed slightly it collapsed down onto the top of the skull.

Dr David Norman, also from Cambridge, who took part in the research, said: “As we can't see the lobes of the brain itself, we can't say for sure how big this dinosaur's brain was.

“Of course, it's entirely possible that dinosaurs had bigger brains than we give them credit for, but we can't tell from this specimen alone.

“What's truly remarkable is that conditions were just right in order to allow preservation of the brain tissue – hopefully this is the first of many such discoveries.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments