Cancer halted in five patients after treatment with own genetically modified cells

Results of the early-stage trial demonstrate that it may be possible to use the gene-therapy technique to control cancers in relapsed patients

A new form of cancer treatment has resulted in five patients experiencing complete remission of their disease with no detectable cancerous cells, scientists announced today.

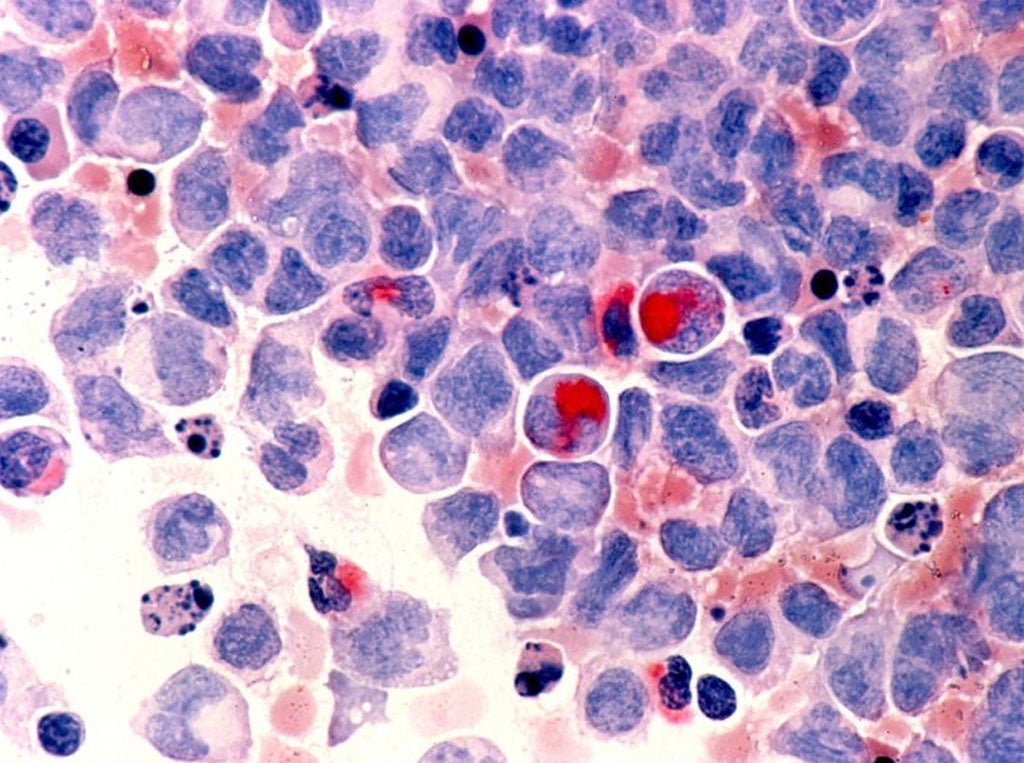

The patients had all experienced a serious relapse of a form of cancer of the white blood cells, called B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, before they received transfusions of their own immune cells that had been genetically modified with an extra cancer-fighting gene.

Doctors treating the patients said that the results of the early-stage trial demonstrate that it may be possible to use the gene-therapy technique to control cancers in relapsed patients so that they can undergo a bone-marrow transplant with a donor's blood stem cells, leading to a complete cure.

The patients had initially undergone chemotherapy to control their cancers but, as so often happens, the disease returned and could not be treated further by the same approach because the cancerous cells had developed resistance to the drugs.

Scientists at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre in New York developed a form of targeted immunotherapy based on inserting an additional gene into the patients' white blood cells that enabled these cells to identify and destroy any cancerous cells circulating in the bloodstream.

"Patients with relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia resistant to chemotherapy have a particularly poor prognosis," said Renier Brentjens of the cancer centre and lead author of the study published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"This ability of our approach to achieve complete remissions in all of these very sick patients is what makes these findings so remarkable and this novel therapy so promising," Dr Brentjens said.

Following the targeted immunotherapy, four of the five patients underwent a bone marrow transplant and to date three of these four have remained in remission for between five and 24 months - with one patient dying from complications unrelated to the cancer therapy.

"By serving as a bridge to stem-cell transplants, this therapy could potentially help cure adult patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia that has relapsed and who are chemotherapy resistant. Otherwise, these patients have a virtually incurable disease," Dr Brentjens said.

"We need to examine the effectiveness of this targeted immunotherapy in additional patients before it could potentially become a standard treatment for patients with relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia," he said.

The results of this small study are a good example of why many researchers are so excited about immunotherapy's potential, said Professor Paul Moss, who runs the Birmingham Cancer Research UK Centre and was not involved with the study.

"Although this treatment may not itself be a cure, it does seem to be able to produce remissions in patients whose [cancer] has relapsed. This can then make patients eligible for stem cell transplantation - which can lead to a cure," Professor Brentjens said.

"It's just one of several similar approaches being tested in clinical trials around the world, including here in the UK," he said.

"Although it's early days for these trials, the approach of modifying a patient's T-cells [white blood cells] to attack their cancer is looking increasingly like one that will, in time, have a place alongside more traditional treatments like chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery," he added.

Michel Sadelain, director of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering, said the findings were very exciting and a major achievement in the field of targeted immunotherapy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments