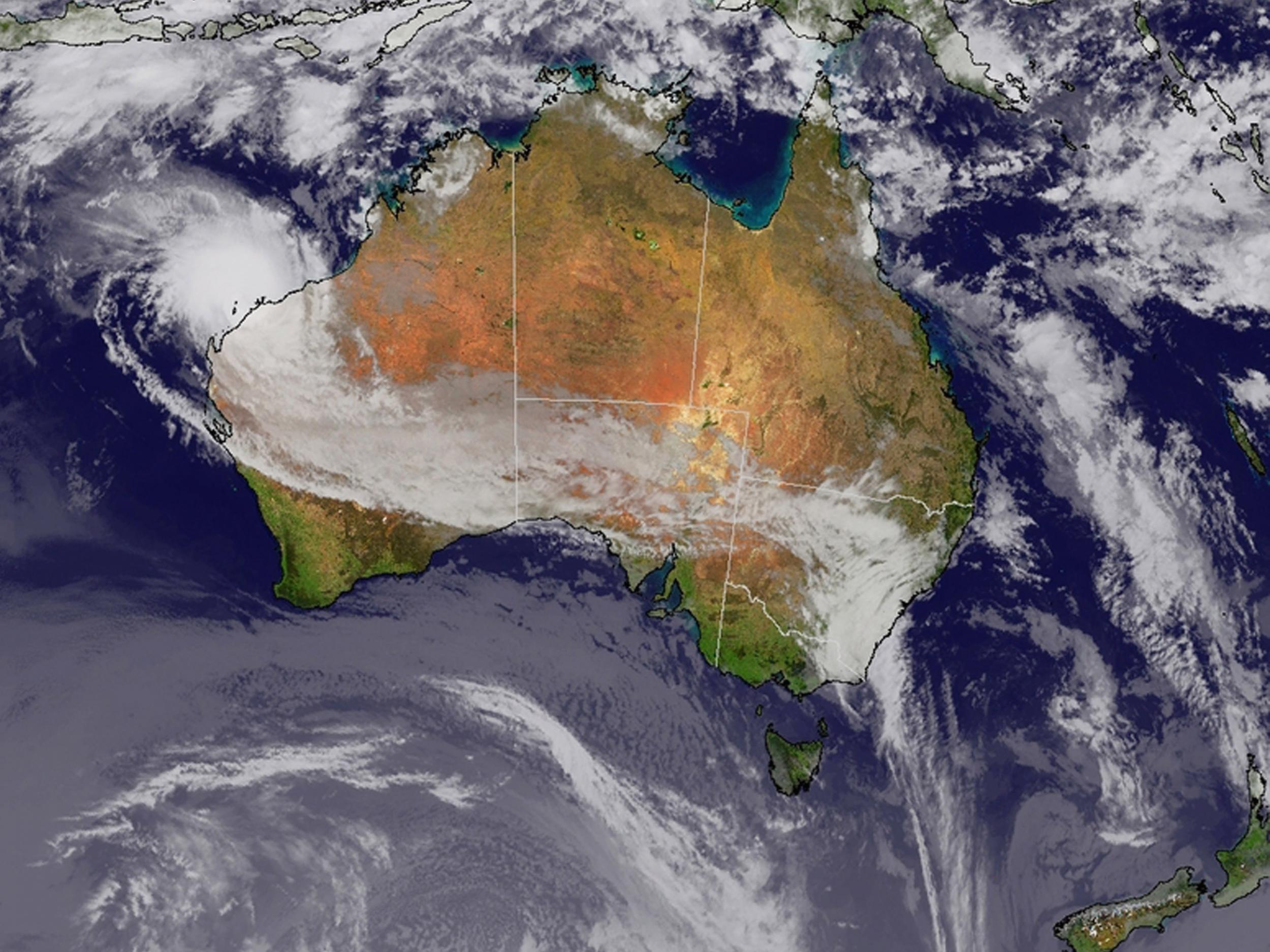

Ancient supercontinent mysteries revealed after 1.7 billion-year-old chunk of Canada found stuck to Australia

Rocks found in northern Queensland reveal area originated in continent of North America as it was being formed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A chunk of what is now Canada broke away from the rest of North America and collided with Australia around 1.7 billion years ago, according to a new study.

A team of geologists examining rocks found in northern Queensland concluded some of them did not appear to have originated in Australia, and had characteristics more common among those found in Canada.

They say the discovery indicates the region surrounding present-day Georgetown in northern Queensland broke apart from the continent of North America during its early formation and smashed into what is now known as Australia.

“Our research shows that about 1.7 billion years ago, Georgetown rocks were deposited into a shallow sea when the region was part of North America,” said Adam Nordsvan, a PhD student at Curtin University, who led the study published in the journal Geology.

“Georgetown then broke away from North America and collided with the Mount Isa region of northern Australia around 100 million years later.”

The discovery provides scientists with new evidence about the formation of the ancient supercontinent, Nuna – a land mass made up of many of the continents we know today.

Over millennia, the Earth’s continents have slowly moved around, reorganising themselves into different combinations, and Mr Nordsvan and his collaborators are trying to understand some of these ancient movements.

“This was a critical part of global continental reorganisation when almost all continents on Earth assembled to form the supercontinent called Nuna,” said Mr Nordsvan.

Nuna existed long before the more well-known supercontinent of Pangaea, which was formed around 335 million years ago.

The research revealed that as Nuna began breaking apart around 300 million years after the initial collision, the Georgetown area stayed where it was.

The collision also produced a mountain range, the same phenomenon that occurred when India smashed into the rest of Asia around 55 million years ago, forming the Himalayas.

“Ongoing research by our team shows that this mountain belt, in contrast to the Himalayas, would not have been very high, suggesting the final continental assembling process that led to the formation of the supercontinent Nuna was not a hard collision like India’s recent collision with Asia,” said Professor Zheng-Xiang Li, another Curtin University geologist, who co-authored the study.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments