Battle against cancer: Scientists develop first 3D computer model of how a solid tumour grows

The virtual tumour allows researchers to imagine what happens when cancer cells begin to divide and mutate within a solid structure

The first three-dimensional computer model of how a solid tumour grows, mutates and evolves has been developed by scientists who say it will help them to understand how lethal cancers develop resistance to drugs and chemotherapy.

A mathematical construction of the complex evolution of a cancerous tumour has already pointed to the most dangerous tumour cells being those where the DNA mutates in such a way that the cells break away to move around the body, the scientists said.

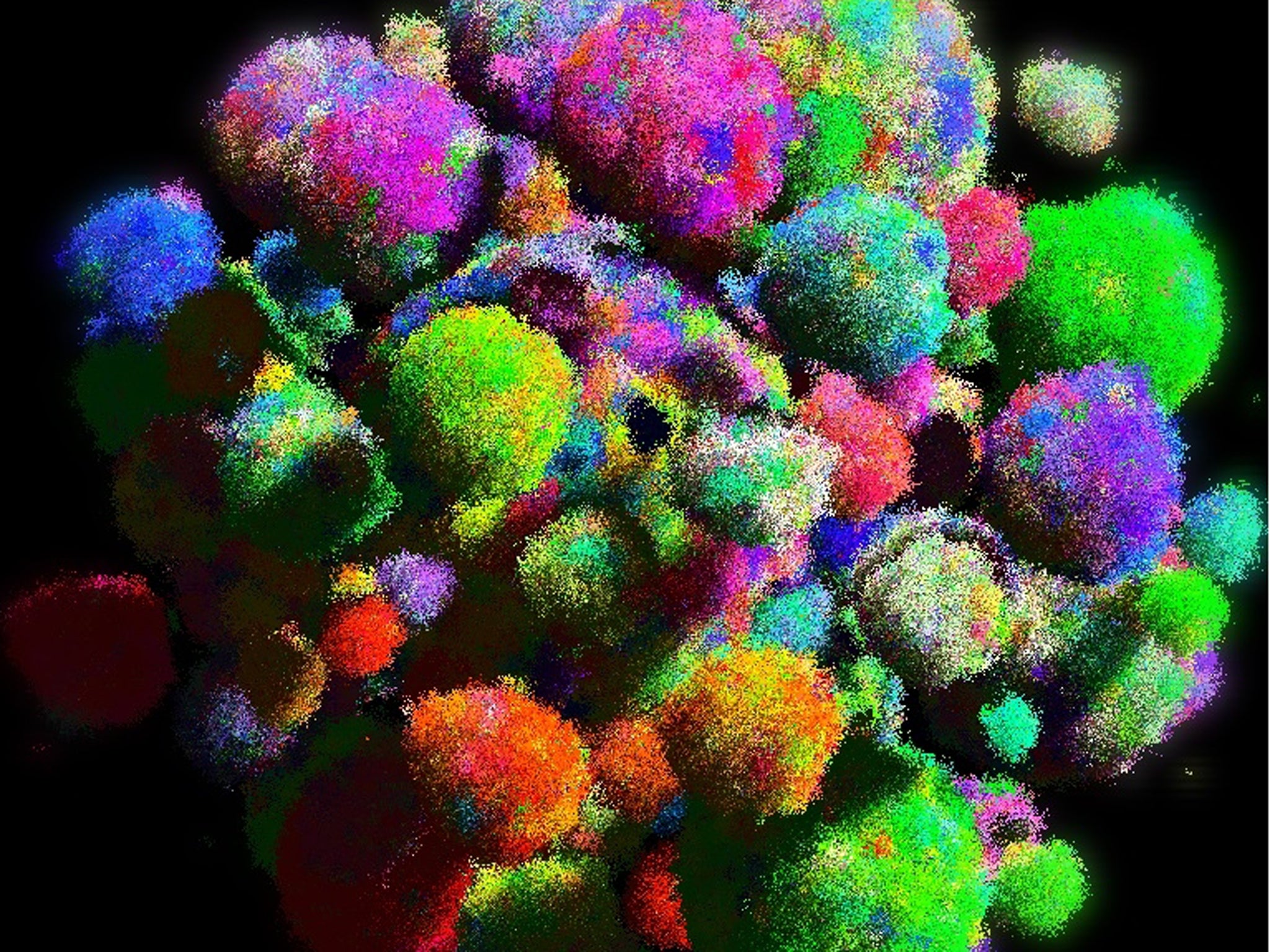

The virtual tumour allows researchers to imagine what happens when cancer cells begin to divide and mutate within a solid structure, with the different coloured clusters of cells representing the various genetic “clones” within the evolving tumour (shown here).

“Previously, we and others have mostly used non-spatial models to study cancer evolution. But those models do not describe the spatial characteristics of solid tumours. Now, for the first time, we have a computational model that can do that,” said Martin Nowack, professor of mathematics and biology at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“The majority of the mathematical models in the past counted the number of cells that have particular mutations, but not their spatial arrangement,” Professor Nowack said. Yet it is the spatial structure of a tumour that plays a key role in its growth and evolution, he said.

Research over recent years has shown that cells within a tumour continue to mutate. Some of the mutations are harmless but others, called “drivers”, can allow a cell to divide faster or live longer, even in the presence of anti-cancer drugs.

The computer model visualises how this process happens in three dimensions over time, according to a study published in the journal Nature. It also shows how the spatial arrangement can allow some cells to migrate away from the tumour to establish metastatic tumours elsewhere in the body, the scientists said.

“Cellular mobility makes cancers grow fast, and it makes cancers homogenous in the sense that cancer cells share a common set of mutations,” Professor Nowak said.

“It is responsible for the rapid evolution of drug resistance. I further believe that the ability to form metastases, which is what actually kills patients, is a consequence of selection for local migration,” he said.

Bartomiej Waclaw of the University of Edinburgh, and lead author of the study, said: “Our approach does not provide a miraculous cure for cancer. However, it suggests possible ways of improving cancer therapy. One of them could be targeting cellular motility [local migration] and not just growth, as standard therapies do.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments