Babies can see things that adults can’t, but are unable to tell them, research finds

Three- or four-month old babies are able to spot differences in pictures that adults can’t — but the skill quickly disappears, as a way of helping us to survive

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Babies can see things that adults can’t — but don't have any way of telling us about them.

Babies who are between three- to four-months-old are able to see differences in pictures with far more detail than older people, meaning that they can see colours and objects in a way that grown adults never will be able to. The ability quickly disappears after about five months, making way for more evolutionarily useful processes.

Many things that look identical to adults will actually appear wildly different to babies. And it is all down to a process called “perceptual constancy”, according to a report from Scientific American.

It is just one of the many skills that changes as we grow from being babies. We also lose the ability to see subtle differences in monkey faces, and to tell speech sounds in languages that aren’t heard regularly.

That process allows humans to be able to tell when the environment has changed the look of something. If a child goes out of a dark cave and into the light, for instance, the apparent colour of its skin will change — but it is important that the human eye and brain can account for that change of light, and recognise that the child is actually the same person.

The skill appears to developed months after birth, probably showing that it is a characteristic acquired through evolution as a way of ensuring our safety and survival.

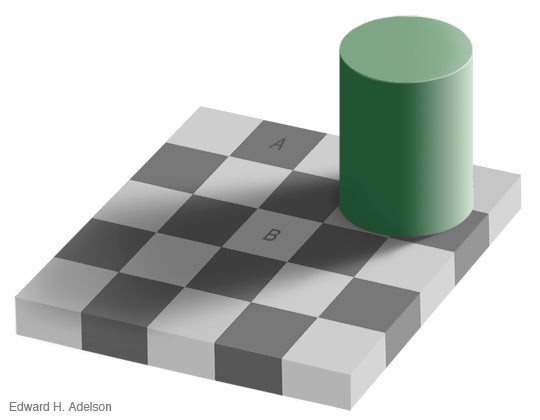

But for babies that haven’t yet acquired the skill, some images will look wildly different. A number of optical illusions rely on this strange quirk — tricking the brain into thinking that something has changed colour by giving the appearance of a shadow, for instance.

The way children acquire the skill was explored in a study, published in December in Current Biology. That took 42 babies and attempted to work out how they see different, ambiguous images — and found that the young ones could compensate for the strange illusions in a way that older children weren’t.

It found that children have a “striking ability” to tell between differences in images when they are three- to four-months-old. But that skill falls away at around five months, and becomes even less strong when babies get the ability to tell between glossy and matte substances a couple of months later.

The babies can’t talk, or tell anyone about the differences that they see.

So the study worked on the previously proved basis that babies will look longer at something that is new to them. Scientists could show the babies two pictures, and look for whether they looked at the picture like it was a new thing or an old one — and so test whether or not the babies appeared to be able to tell the difference.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments