'As close to an HIV cure as we've seen': Breakthrough hailed as radical treatment works on baby born HIV-positive in Atlanta

US team gave child stronger, faster dose of antiretroviral drugs straight after birth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists appeared a step closer to conquering the Aids virus after US doctors confirmed they had cured an infant born with HIV through a course of antiretroviral drugs, the first time this has ever been recorded.

Doctors in Atlanta said a two-and-a-half-year-old child from Mississippi was born HIV positive and received a three-drug infusion within 30 hours of its birth, a stronger and far swifter dose than normally administered.

Last night scientists confirmed that the child, whose identity has not been disclosed, has since been off medication for HIV for over a year, is believed no longer to be infectious.

Last night scientists were pouring over the findings, unveiled at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Atlanta. "You could call this about as close to a cure, if not a cure, that we've seen," said Dr Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health. Much of the success of treatment is believed to be down to the swiftness and intensity of the antiretroviral dosage that was so potent. Usually a child is given a course of one drug.

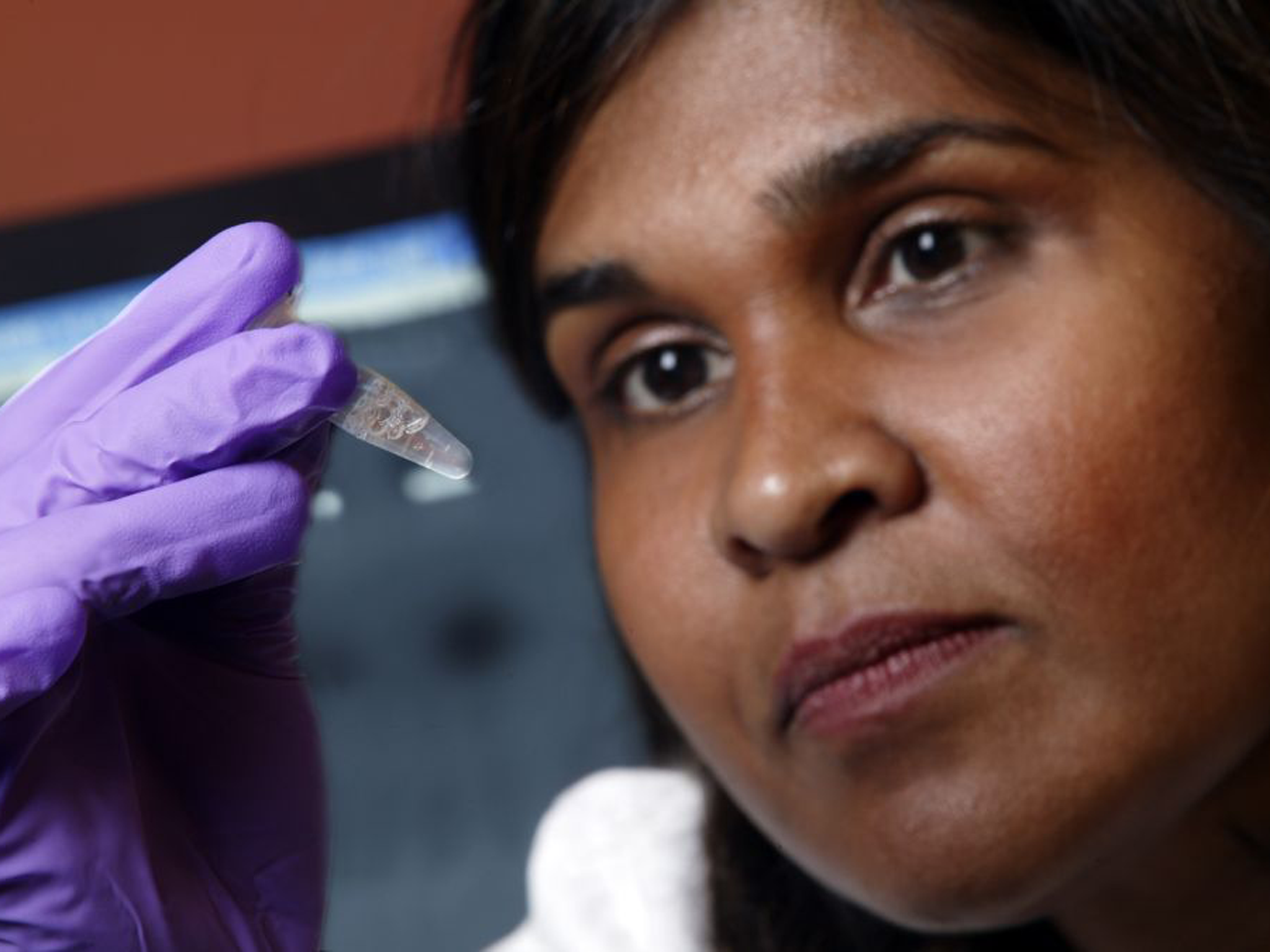

While the findings are encouraging, scientists warned they are not the definitive cure for HIV. It is thought to have been the speed and intensity of the action that knocked out HIV in the baby's blood before it could form hideouts in the body. But not all traces of the virus have been eradicated. Dr Deborah Persaud of Johns Hopkins Children's Center, who led the investigation, said that the child was in effect "functionally cured", meaning in long-term remission even if all traces of the virus haven't been completely eradicated.

The treatment would not work in older children or adults as the virus will have already infected cells. The number of babies born with HIV in developed countries has fallen dramatically with the advent of better drugs and prevention. Typically, women with HIV are given antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy to minimise the virus in their blood. Their babies go on courses of drugs, too, to reduce their risk of infection further. The strategy can stop around 98% of HIV transmission from mother to child.About 300,000 children were born with HIV in 2011. In the US such births are very rare as HIV testing and treatment long have been part of prenatal care. "We can't promise to cure babies who are infected. We can promise to prevent the vast majority of transmissions if the moms are tested during every pregnancy," said Dr Hannah Gay, of the University of Mississippi.

The only other person considered cured of the AIDS virus underwent a bone marrow transplant from a donor naturally resistant to HIV. Timothy Ray Brown of San Francisco has not needed HIV medications in the five years since that transplant. The Mississippi case shows "there may be different cures for different populations of HIV-infected people," said Dr Rowena Johnston of amFAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research. That group funded Persaud's team to explore possible cases of pediatric cures. It also suggests that scientists should look back at other children who've been treated since shortly after birth, including some reports of possible cures in the late 1990s that were dismissed, said Dr. Steven Deeks of the University of California, San Francisco. "This will likely inspire the field, make people more optimistic that this is possible," he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments