Vast 5,600-year-old religious centre discovered near Stonehenge

The centre was built more than 1,000 years before the stones of Stonehenge were erected

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A huge, prehistoric religious and ceremonial complex has been discovered near Britain’s most famous prehistoric temple Stonehenge.

Its discovery is likely to transform our understanding of the early development of Stonehenge’s ancient landscape.

Built about 5,650 years ago – more than 1,000 years before the great stones of Stonehenge were erected – the 200m-diameter complex is the first major early Neolithic monument to be discovered in the Stonehenge area for more than a century.

The newly discovered complex, just over a mile and a half north-east of Stonehenge, appears to have consisted of around 950m of segmented ditches – and potentially palisaded earthen banks – arranged in two great concentric circles.

So far, archaeologists have located and excavated around 100 metres worth of the outer ditch. It is not yet known how much, if any, of the rest of the monument has survived.

The new discovery shows that hundreds of years before Stonehenge existed the entire area was even more sacred and ritually active than archaeologists had thought.

Up till now, apart from more than 20 giant tombs – the so-called ‘long barrows’ – the only known early Neolithic monument in the Stonehenge area was a large circular religious and ceremonial ‘causewayed enclosure’ nicknamed Robin Hood’s Ball, 2.5 miles north-west of Stonehenge.

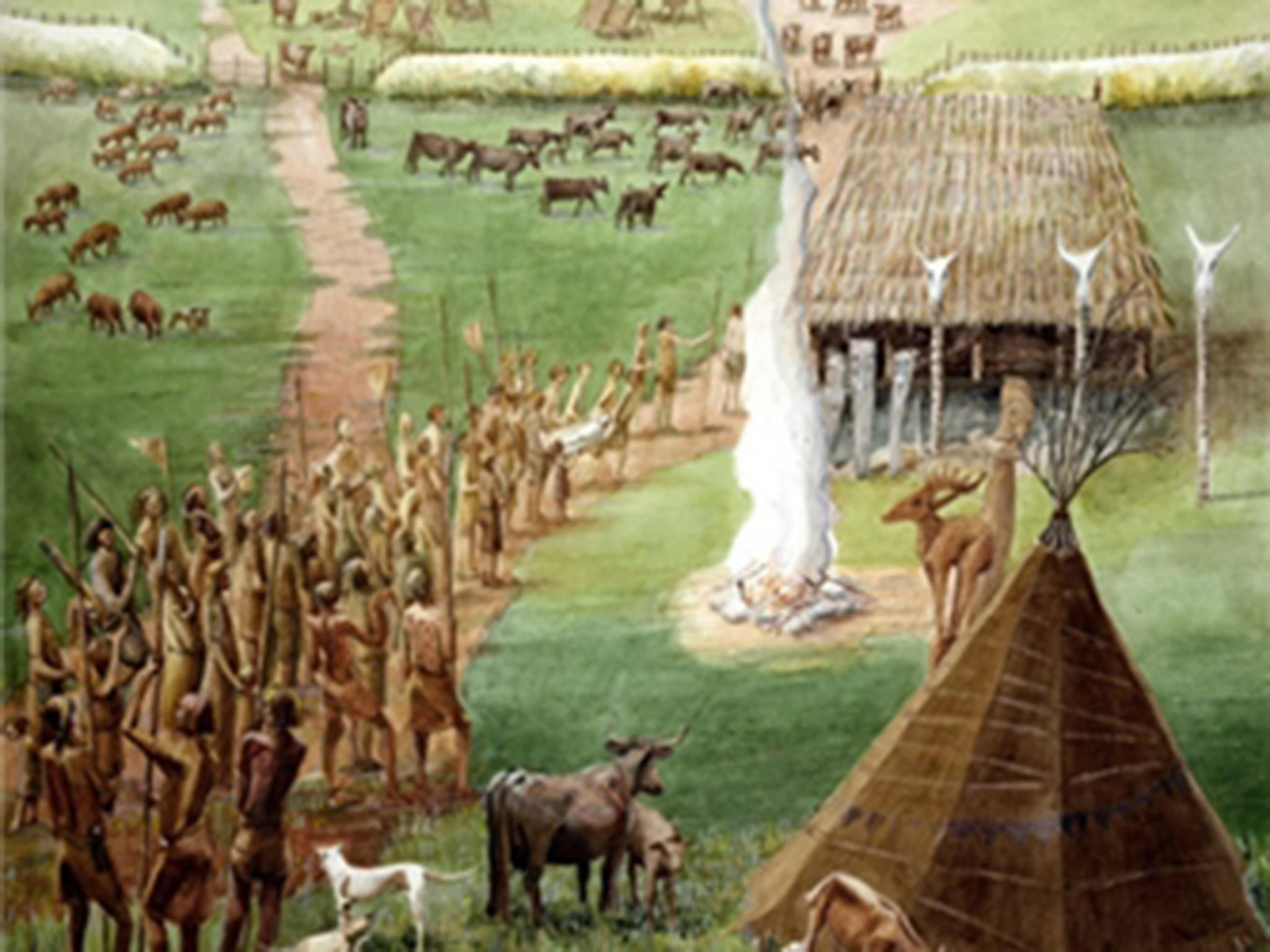

Causewayed enclosures – so-called because their ditches are “crossed” by multiple causeways – are among the most enigmatic of prehistoric monuments. Around 70 are known in England. Others exist on the continent, in Germany, Denmark and elsewhere.

Their precise original function remains a mystery, but the scant available evidence suggests that they were used for a mixture of ceremonial, religious, political and mortuary roles.

Located at Larkhill, Wiltshire, the newly found “causewayed” enclosure, dating from around 3650BC, is in an area covered by modern military buildings and other installations.

Its discovery strongly suggests that the remains of other important prehistoric monuments probably still survive undetected in the area.

The discovery suggests that Stonehenge’s ancient sacred landscape still has many secrets to reveal. Indeed, it follows fast on the heels of another discovery half a mile to the south-east, made just three months ago, when archaeologists found what, back in the Stonehenge era, had been a vast circle of giant timber posts.

Although nobody suspected that a second causewayed enclosure would be discovered near Stonehenge, its presence there is consistent with the distribution of such monuments across the country.

More than a third of causewayed enclosures occur in pairs or clusters of three or occasionally four. It is conceivable that clan or tribal rivalries saw them compete to build the most impressive enclosures.

So far, archaeologists from Wiltshire-based Wessex Archaeology have excavated around 100m of ditch, probably representing around 17 per cent of the monument’s outer circuit. That investigation has already enabled them to get a sense of some of the rituals that were carried out there.

The mortuary or other religious ceremonies may well have involved feasting on large quantities of beef – and the use and deliberate smashing of ceramic bowls. Some fragments of the smashed bowls and cattle bones were then placed in the ditch ends, flanking the complex’s multiple entrances.

Some of the ditches were also used for the ritual deposition of human skull fragments, potentially re-deposited from other funerary monuments like the nearby long barrow tombs.

So far, the archaeologists have found four human cranial fragments in one ditch location, probably belonging to a single individual. However, there are likely to have been additional human skull fragment ritual depositions in some of the monument’s other ditches.

During ritual feasts, each bowl would have held up to six litres of beverage or partially liquid food, potentially meat broth. Scientific tests are due to be carried out on the fragments to definitively determine what they originally contained.

So far, the remains of 15 such bowls, which were up to 25cm in diameter, have been found. Each had been deliberately smashed.

However, it’s likely that more than 200 such bowls and the bones of dozens of slaughtered cattle from a succession of feasts were originally placed in the complex’s ditches.

Because the bowls, including a particularly fine one made in Neolithic Devonshire style, were all deliberately smashed, it’s likely that the cattle and the bowls were viewed not just as aspects of a ritual feast but also as sacrifices to the gods.

The cattle bones, bowl fragments and human material had been carefully selected. In the ritual ditch depositions, cattle were represented only by their leg bones, while humans were only represented by skull fragments. The smashed bowls were represented solely by their finer looking and sometimes decorated rims and upper portions.

The causewayed enclosures – both the newly discovered one and Robin Hood’s Ball – are the third oldest type of monument in the Stonehenge landscape.

Only the very early Neolithic long barrows – and an even earlier group of pre-Neolithic potentially totem-pole-style wooden posts – are older. The main phase of Stonehenge itself was constructed around 1,150 years after the building of the causewayed enclosures. However the newly discovered monument appears to have been revered by local people for millennia. Indeed, the recent archaeological excavations unearthed a pottery urn which had been ritually buried in the causewayed enclosure ditch almost 1,900 years after the monument had been constructed.

A leading Wessex Archaeology prehistorian, Matt Leivers, said: “The newly found site is one of the most exciting discoveries in the Stonehenge landscape that archaeologists have ever made.

“It transforms our understanding of the intensity of early Neolithic activity in the area.”

The previously unknown prehistoric complex was discovered as developers were preparing to build houses on Ministry of Defence land to accommodate British Army personnel returning from Germany. The dig has been funded by the MoD’s Defence Infrastructure Organisation.

Archaeologist Martin Brown of the UK-based global consultancy company WYG, responsible for the Larkhill housing development project, said: “These discoveries are changing the way we think about prehistoric Wiltshire and about the Stonehenge landscape in particular.

“The Neolithic people whose monuments we are exploring shaped the world we inhabit. They were the first farmers and the first people who settled down in this landscape, setting us on the path to the modern world.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments