Secrets of medieval Europe's large-scale publishing industry revealed

Continent’s craftsmen discovered a way of transforming animal skins into wafer-thin sheets for use in era's finest books

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The mystery of how the medieval world made some of its finest books has at last been solved – after 700 years. New research is revealing the trade secrets of Europe’s very first large-scale commercial publishing industry.

Several generations before the widespread introduction of paper into Christian Europe, the continent’s craftsmen discovered a way of transforming animal skins into wafer-thin sheets for use as pages in medieval books.

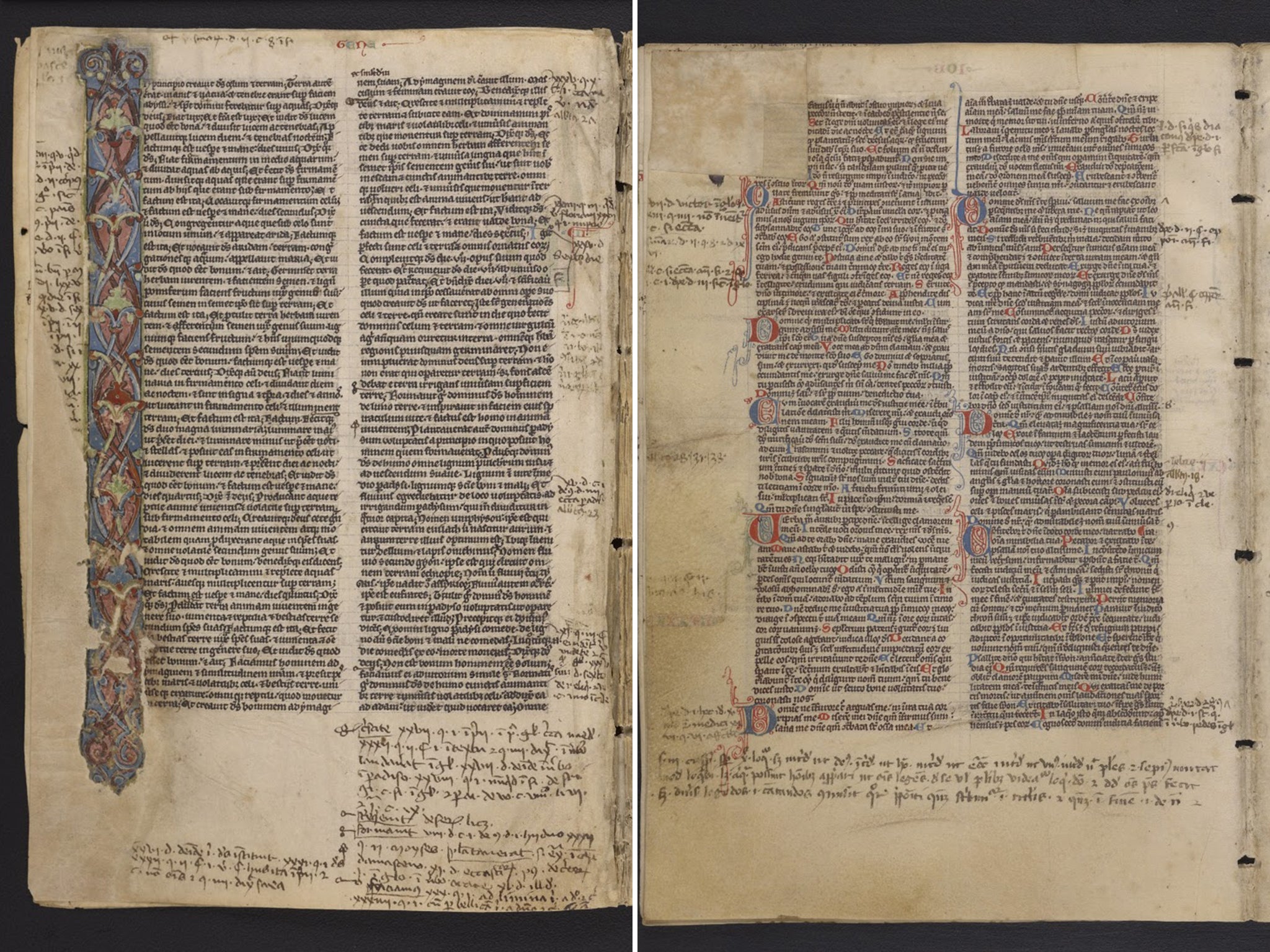

They succeeded in making animal skin ‘paper’ that was just 1/15th (and sometimes even 1/18th) of a millimetre thick – and armed with this new technology, they were able to mass produce the world’s first lightweight books – an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 handwritten bibles.

The craftsmen kept the tricks of their trade strictly under wraps – and, for the past 700 years, most historians and others have believed that 13th century ultra-fine parchment makers must have used the skins of rabbits, squirrels and new born, still born and even aborted calves to make their super-thin products.

But now, 700 years after deteriorating economic conditions forced Europe’s craftsmen to stop producing super-thin parchment, scientists have discovered that they hardly ever used such young calves, let alone rabbits and squirrels, but instead developed a method of making skin from adult sheep, adult goats and young eight week old cattle look like the skins of new-born calves.

In a series of tests carried out by British scientists on 72 lightweight parchment bibles, made in various areas of medieval Europe, the scientists have discovered that 68% were made of calf skin (many from France and probably some from England), around 6% from adult sheep (mainly from England) and 26% from adult goats (mainly from Italy and southern France).

Scientific research and experimental work, being carried out by scientists from the University of York are now revealing the immense skill that medieval craftsmen had to develop. In order to make goat, sheep and eight week old calf parchment look as fine as if it had all come from new-born calves, the medieval artisans had to immerse the skins in alkali-rich liquefied lime so as to get rid of the fats in those skins by transforming the lipids into a form of detergent. That natural soap not only helped thin the skins but also helped whiten them by dissolving all the ingrained grime and stains.

The alkali in the lime also served to remove the thousands of tiny hairs in the skin – by weakening the chemical bonds which hold protein molecules together.

However, too much exposure to lime would have also turned the skins’ collagen content into gelatine - thus irreversibly swelling and damaging the product. The medieval craftsmen seem to have discovered the precise time required to thin and whiten the skins in the lime, while not destroying them.

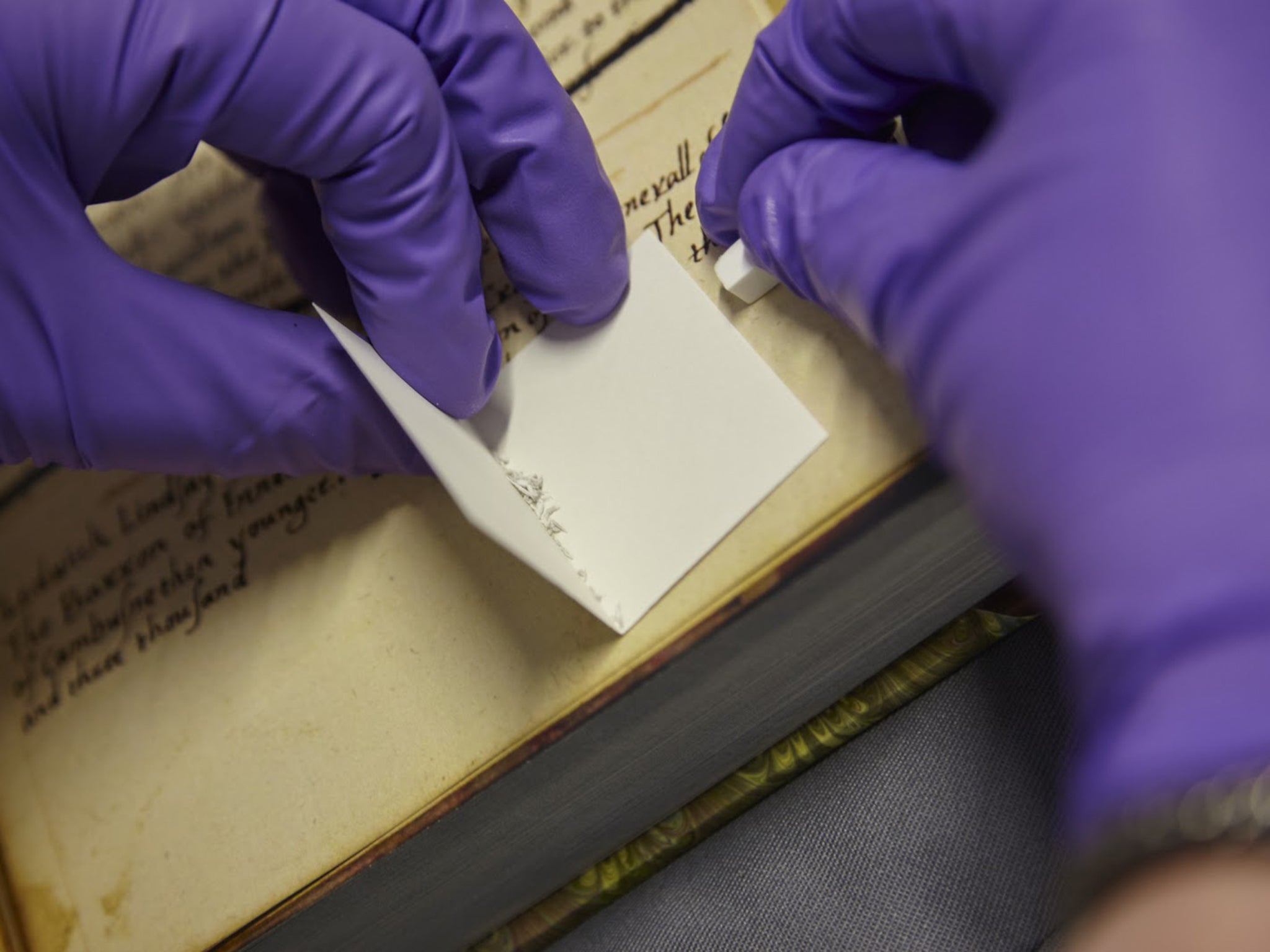

As well as immersing the skins in lime, the artisans also stretched them on wooden frames, scraped them with a special bladed tool – then spent many hours rubbing them with volcanic pumice stone to further thin and smooth them.

The mass production of ultra-thin parchment lasted for around 80 years (from c1220 to c1300). The market that created the demand for it was the huge expansion at that period in the number of so called ‘mendicant’ [begging] highly mobile friars – and in the number of university students. The major mendicant orders of preaching friars (including the Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinians) were established in the first half of the 13th century – and the first dozen great European universities were all set up in Italy, France, England and Spain between 1088 and 1243.

Both the mobile preaching friars and the university students had a need for lightweight portable bibles. At least 20,000 were produced (each being used by several generations of friars and students) – but only around 2000 still survive today, mostly in libraries and archives in France, England, Italy and the USA.

Hand-written in Latin in tiny script (each letter being just two millimetres tall), each bible took thousands of man-hours to make.

Each one cost the 13th century equivalent of several thousand pounds to buy. The major production centres were Paris, Bologna and Oxford.

The new scientific research - led by Dr. Sarah Fiddyment and Professor Matthew Collins, both of the University of York – has involved protein analysis and hair follicle pattern analysis in order to determine the species of the animals used and how old they were when slaughtered. The revelation that parchment was mainly manufactured from eight week old calves and adult sheep and goats and not from new-born calves shows for the first time that 13th century bible production was actually a lucrative by-product of the food industry.

“By carrying out detailed scientific tests on a substantial sample of medieval lightweight portable bibles, we have effectively turned what had been regarded as purely art historical objects into new archaeological data,” said the director of the research project, Professor Matthew Collins.

“This has enabled us, for the first time, to more fully understand the birth of Europe’s first commercial book production industry.

“The research is important not just from that early publishing perspective – but also because those thousands of lightweight bibles played such an important role in the development of Europe’s first universities and the evolution of medieval religious practices”, said Professor Collins.

Much of the research so far has been published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments