Ancient Roman texts shed light on earliest Londoners in one of UK's most important archaeological discoveries

Wooden writing tablets found deeply buried in waterlogged ground near St Paul’s Cathedral

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After almost 2000 years of silence, extraordinary new archaeological discoveries have allowed the first Londoners to speak again.

Dozens of the earliest written texts ever found in Britain were revealed to the world in London on Wednesday morning. The material had been kept totally under wraps for the past two years, while one of Britain’s top Latin experts undertook the painstaking work of transcribing and translating them.

The texts – written on Roman wooden writing tablets and found deeply buried in waterlogged ground just 400 metres east of St Paul’s Cathedral – have given the first ever relatively detailed series of brief written accounts of what London was like in the first forty years of its existence.

The documents include what is probably the earliest manuscript ever found in Britain – as well as what may well be the earliest surviving example of the name London.

They also include the city’s earliest known financial document – dated 8 January, 57 AD, referring to a debt of 105 denarii (around £10,000 in modern equivalent terms). All the ancient documents were found by archaeologists excavating land which is now the site of the new European headquarters of the international financial news and information company, Bloomberg.

The wooden manuscripts reveal the cosmopolitan nature of early London – and the huge variety of people who lived there.

Key characters in the texts include Tertius the brewer, Proculus the haulier, Tibullus the freed slave, Optatus the food merchant, Crispus the innkeeper, Classicus the lieutenant colonel, Junius the barrel maker, Rusticus (one of the governor's bodyguards) and, last but not least, Florentinus the slave.

Others include a businessman, a landowner, a scribe (possibly a military commander’s personal secretary) and a former member of the Emperor’s bodyguard.

Judging by their names and other evidence in the texts, many early Londoners were Celts (almost certainly from Gaul as well as from Britain), Germans (especially some of the city’s military garrison) and possibly Lusitanians (from what is now Portugal).

Of particular importance from a historical perspective, the manuscripts also give additional information on London’s political status. One particularly significant document, dated 22 October, 76 AD is a preliminary judgement made by an imperially-appointed judge. His presence in London demonstrates that the city was directly administered by the emperor (through his provincial governor) – rather than through a locally-elected municipal council or elected local magistrates.

Another indication that London had a special status is a document referring to a member of governor’s personal bodyguard. Its presence in London is additional evidence that the governor was almost certainly based there.

Another manuscript, indicating London’s high status, suggests the presence in the city of a former member of a Roman emperor’s bodyguard unit – the famous Praetorian Guard. But whether he was in London to help train the governor’s guards or whether he was one of his senior officers is not known.

As well as painting a picture of the very first Londoners, the manuscripts also provide a number of tantalising vignettes of life in the provincial capital.

Even at that early stage, the newly-revealed ancient manuscripts demonstrate that London was a major commercial and financial centre. Around 50 per cent of those documents, where the subject matter is known, refer to loans or debts.

One such financial manuscript refers to the “principle and the interest” on a loan and an understanding that it will “be properly repaid in genuine coinage” and states that a man called Aticus (presumably the borrower) has “properly, truly and faithfully promised that [the repayment is] to be given” to a man called Ingenuus (presumably the lender or his agent).

In another document a man seems to be desperately pleading for his business associate to send through some urgently needed funds. “I ask you, by bread and salt, that you send as soon as possible the 26 denarii in Victoriati [older coins with higher silver content] and the 10 denarii of [the man] Paterio.” The total amount was the Roman equivalent of around £3500 – and the need for it seems to have warranted a plea from the heart (“by bread and salt”, probably meaning metaphorically “in the name of our friendship”).

Other manuscripts are about freight transport and trade. One describes how a man called Taurus lost his draft animals – presumably oxen or horses.

“Taurus to Macrinus, [my] dearest Lord, greetings. [I hope you are] in good health.” “Catarrius” took my “beasts of burden away – investments that I cannot replace for [the next] three months.”

Another document is historically very significant because the information in it suggests that Queen Boudica’s revolt probably took place a year earlier (60 AD) than that stated by the Roman historian Tacitus. That’s because the information implies that London, which had been destroyed by Boudica, was up and running again as a city by October, 62 AD.

“I, Marcus Rennius Venustus [have written and say that] I have contracted with Gaius Valerius Proculus that he bring from Verulamium [to London] by the Ides of November, 20 loads of provisions at a transport charge of one quarter denarius for each”

Virtually all the early Londoners and other British-based Romans mentioned in the newly studied documents are individuals who were previously unknown to history.

One particularly interesting exception is an important Gallo-Germanic nobleman called Classicus who, it now seems, was posted to Britain (probably in 61 AD) to reinforce the Roman military presence immediately after Boudicca’s revolt – but who subsequently helped stage an anti-Roman uprising of his own – centred on and around the lower Rhine region in 69-70 AD.

One of the London Roman manuscripts refers to him as the “prefect [lieutenant colonel] of the Sixth Cohort [battalion] of Nervians” – a Gallo-Germanic tribe from what is now Belgium.

Significantly, Classicus (himself a member of a Gallo-Germanic tribe called the Treveri – from around Trier in modern Germany) was almost certainly related to the new Roman Imperial procurator of Britain, Julius Classicianus – and his appointment as prefect of the sixth cohort in Britain may therefore have been due to Classicianus’ influence.

All the ancient documents – written between 43 AD and around 80 AD – were originally unearthed during a Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) excavation (funded by the international financial news organisation, Bloomberg) in 2013 and 2014 – but, at that stage, they were mostly illegible.

But detailed decipherment, transcription and translation work and other research over the past two years has finally succeeded in unravelling what these first Londoners were writing almost two millennia ago

The decipherment has not been an easy task. Originally most of the wooden writing tablets were covered with blackened beeswax, with text inscribed into the wax with metal styluses. Although the wax hasn’t survived, the writing occasionally went through the wax to inadvertently mark the wood. As tablets were reused, in some cases several layers of text built up on the tablets, making them particularly challenging to decode.

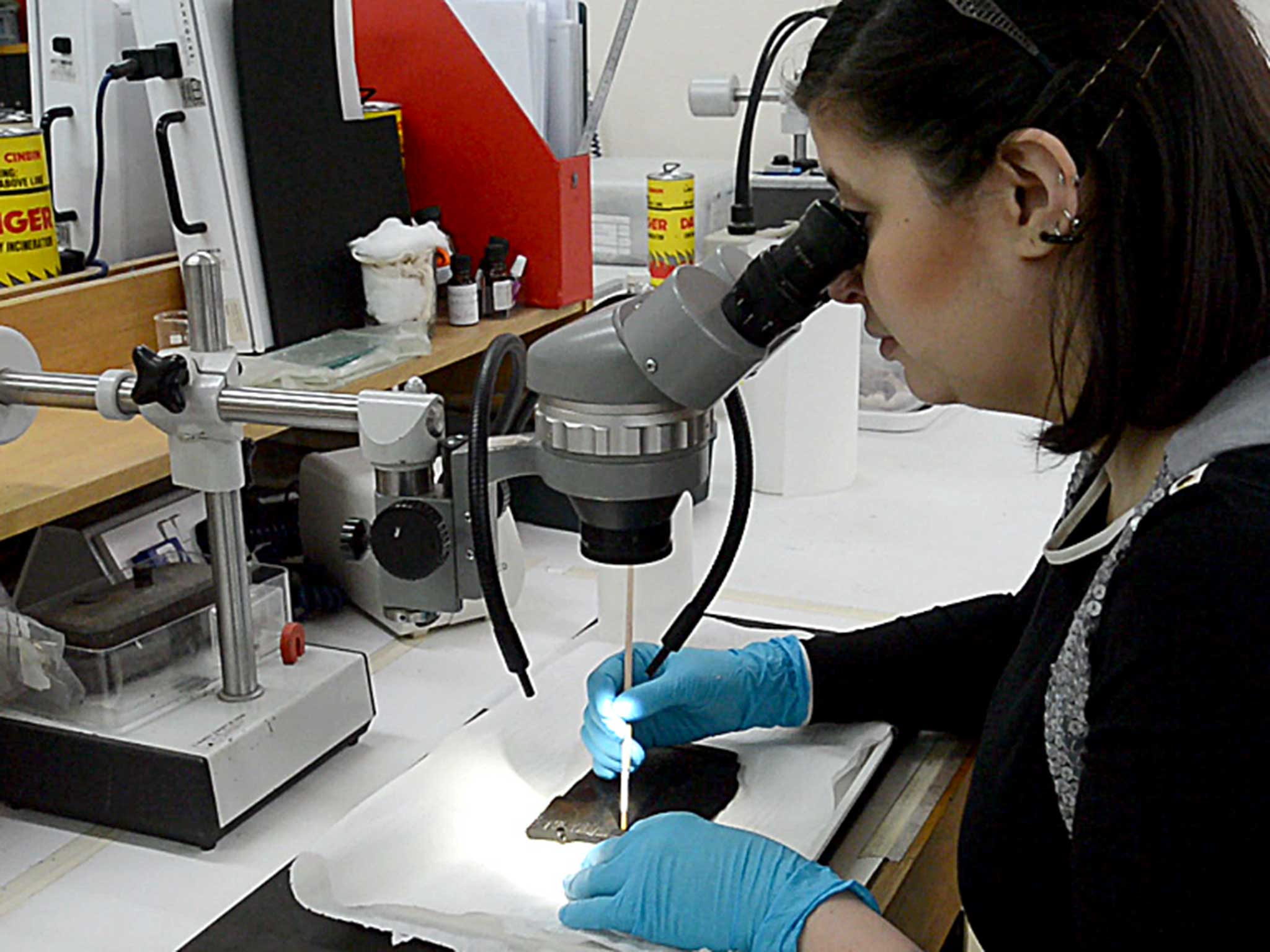

One of Britain’s top classicists and cursive Latin experts, Dr Roger Tomlin of Wolfson College, Oxford, deciphered and interpreted the tablets – often using specially lit photography and microscopic analysis.

“The Bloomberg writing tablets are very important for the early history of Roman Britain, and London in particular,” he said.

The preservation of the tablets is in itself remarkable, as wood rarely survives when buried in the ground. The wet mud of the marshy valley of the Walbrook, a river that ran through the area in the Roman period (and still survives – as a subterranean sewer waterway), stopped oxygen from decaying the wooden tablets, preserving them in excellent condition.

Once excavated, the fragile tablets were kept in water before MOLA conservators carefully cleaned them and, using a waxy substance, PEG, which replaced some of the water content, treated them before they were freeze-dried.

Over 700 artefacts from the Bloomberg site excavation will be displayed in a public exhibition space that will sit within the new Bloomberg building, including the earliest-dated writing tablet from Britain. The permanent exhibition will also feature London’s Roman temple of Mithras and will open in autumn, 2017.

The full research on the newly-revealed ancient manuscripts is published in ‘Roman London’s first voices: writing tablets from the Bloomberg London excavations, 2010–14’ (MOLA, £32)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments