Impose limit of less than nine antibiotic doses per person a year to help prevent superbugs, say experts

Paper in the journal Science says urgent action must be taken to reduce the rise in deadly drug-resistant bacteria

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

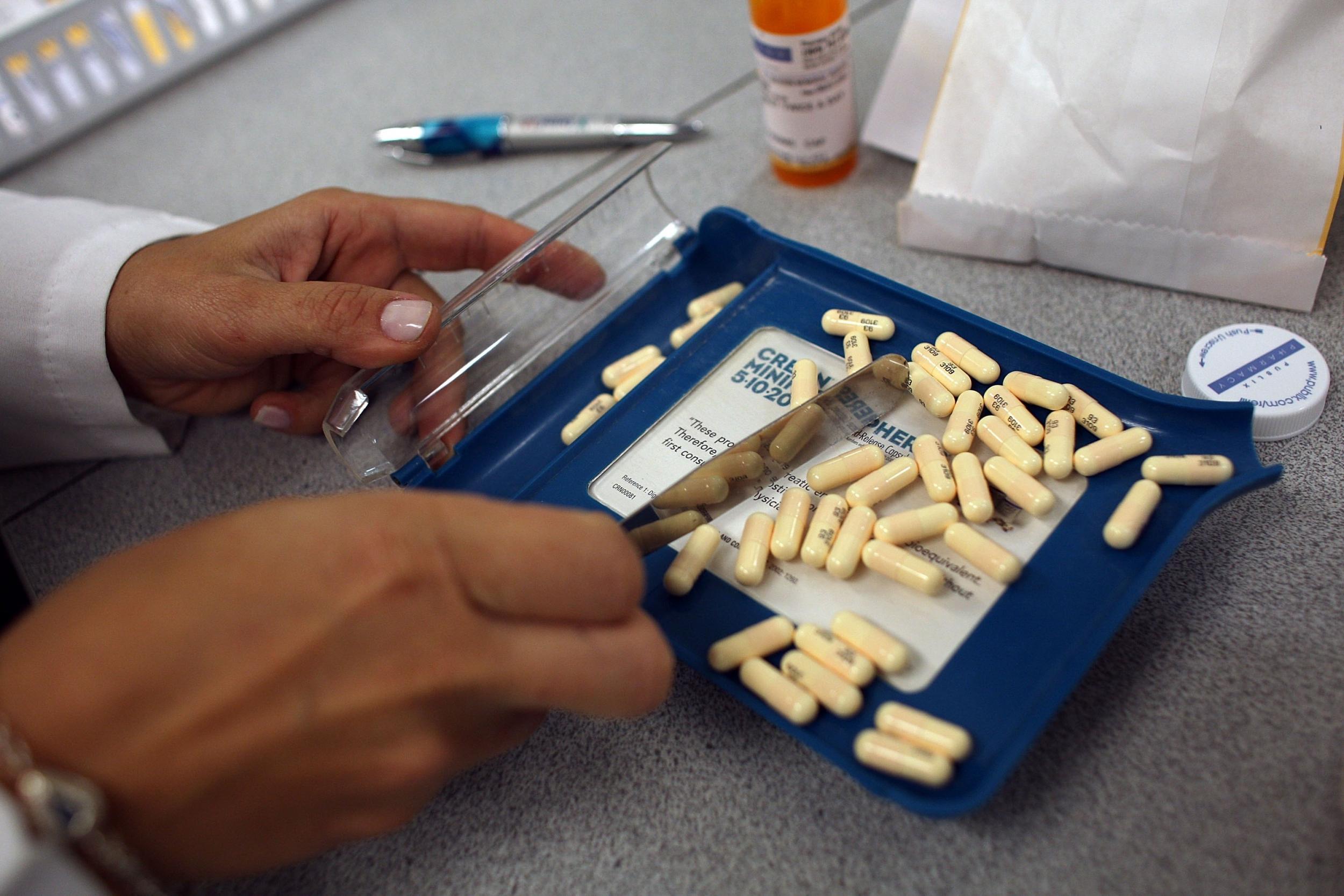

Antibiotics should be limited to an average of less than nine daily doses a year per person in a bid to prevent the rise of untreatable superbugs, global health experts have warned.

Writing in the prestigious journal Science, they called on world leaders gathering for a special United Nations meeting on the issue next month to take decision action to reduce antimicrobial resistance.

This threatens to send medicine back to the days before the discovery of the first antibiotic, penicillin, when people could die from a simple scratch in the garden.

A superbug resistant to the antibiotic of “last resort”, colistin, was found in the UK in December in human cases and on three farms.

Under David Cameron, the UK led calls for global action to address the problem. Mr Cameron warned of potentially “catastrophic consequences” of failing to do so as he announced plans to try to halve the number of drug-resistant infections in Britain by 2020.

It has been estimated that 10 million people could die every year worldwide by 2050 as a result of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

In the paper, experts from the UK, US and China wrote: “We propose that no country consume more than the current median global level – 8.54 defined daily doses per capita per year. We estimate that this would lower overall use by 17.5 per cent globally.”

This is an average for each member of the population, so people in dire need of life-saving antibiotics, such as those with compromised immune system or surgery patients, would still be able to have substantially more than this figure.

The experts added: “Further reductions could be achieved through public campaigns, aimed at physicians and patients, to discourage inappropriate antibiotic use, particularly in response to seasonal influenza.”

Flu is a virus, so antibiotics have no effect, but many people demand the drugs from their GPs regardless. They also do not work against most colds, most coughs or sore throats.

Our immune system can also handle mild bacterial infections without any outside help.

The paper said there was “sizable potential” to cut antibiotic use in agriculture.

The drugs are given to livestock not because they are sick, but to make them grow faster.

Giving regular and low doses of antibiotics in this way has been described as the “perfect” way to produce resistant bacteria because it creates an evolutionary pressure for resistance to develop without actually killing the bacteria.

“We propose complete global phasing out of the use of antimicrobial growth promoters,” the paper said.

“A deadline of five years would be appropriate, given the urgency of the problem.

“This could avert much of the projected 67 per cent increase in use for farm animals between 2010 and 2030.”

The experts also said that placing restrictions on antibiotic effluents – from pharmaceutical manufacturing, agricultural operations and hospital waste – should be an “urgent priority”.

These can get into rivers and contribute to the build-up of resistant genes in the water and soil.

Antibiotics are essentially the product of chemical warfare waged by fungi, molds and some forms of bacteria.

So bacteria that make humans sick can be countered with a semi-synthetic drug made from another bacteria that kills it.

Bacteria reproduce – and therefore evolve – quickly and the huge numbers of individuals. So a drug that kills 99 per cent of them will soon result in a new population of bacteria descended from the one per cent who were able to survive.

Dr David Brown, chair of the science committee of the charity Antibiotic Research UK, said the spread of antibiotic resistance was a global threat.

"What we need to be aware of is there are vast differences in patients' needs," he said.

"People with cystic fibrosis, people with immune suppression or people who have had difficult invasive surgery are going to need more [than the proposed average limit].

"It's important that these people get the antibiotics they need, but equally it is important we reduce the unnecessary use for less severe conditions."

The Department of Health said the Government was "leading the fight against drug-resistant infections", working with the UN and G7 and G20 groups of countries.

“Drug-resistant infections have a devastating potential and we have been clear that world needs to act now in order to save millions of lives," it said in a statement.

"We have already committed to halving the inappropriate prescription of antibiotics in humans by 2020. We have already made good progress.

"The NHS has already taken action with over 2.6 million fewer prescriptions in 2015-16. This is a reduction of over seven per cent compared with 2014."

The Government has also launched a £268m 'Fleming Fund', named after Sir Alexander Fleming who discovered penicillin, to help other countries improve monitoring of antibiotic use.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments